For the Weak and the Weary

A Spirituality of Imperfection

For Sunday February 5, 2006

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year B)

Isaiah 40:21–31

Psalm 147:1–11, 20c

1 Corinthians 9:16–23

Mark 1:29–39

|

Isaiah, by Duccio di Buoninsegna, 1308-11, tempera on wood. |

A few days ago hospice care experts advised our family that my mother will likely die within weeks. Mom blessed many people with her self-sacrificing ways, including twenty-five years of loving service as organist and choir director at our small Presbyterian church (1967–1992). Measured in worldly acclaim she led an unremarkable life; if you "googled" her name you would only get "no entries found." Nor did Mom live an easy life. Born in 1922, she experienced the Great Depression as a little girl, married at the age of eighteen, then endured the tumult of World War II. After raising six children in thirty-three years of marriage, she braved a divorce at the age of fifty-one that forced her to enter the job market for the first time. With no marketable work history, she spent twenty years at a clerical job earning close to minimum wage. Most confounding of all, in her sixties Mom began a long slide into the tentacles of clinical depression from which nothing disentangled her—hospitalizations, drugs, shock therapy, counseling, the support of her entire family, church, and certainly prayer. Last week she stopped eating. When nurses tried to feed her she clenched her mouth shut or turned her head. When she did take a spoonful of peas or a bite of tangerine she hid the food in her mouth like a dip of snuff, then spit it out a half hour later.

So, death—an outstanding debt that we all owe—will end a discouraging struggle for Mom and my family. I will grieve for her and miss her, but not without hope. I believe that God will at long last welcome her to a new life of healing wholeness after her fair share of life's bumps and bruises.

|

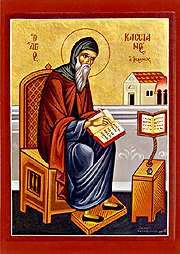

John Cassian. |

In the Old Testament reading this week the prophet Isaiah depicts a mighty God enthroned in the heavens who looks down on humanity as so many tiny grasshoppers. His God "brings princes to naught and reduces the rulers of this world to nothing; he blows on them and they wither, and a whirlwind sweeps them away like chaff." Turning his gaze to the night sky, Isaiah worships this God who "brings out the starry host one by one, and calls them each by name. Because of his great power and mighty strength, not one of them is missing."

But Isaiah's mighty God, so Absolutely Other, does not disregard the lowly, the insignificant, the obscure or the unimportant. Be assured, he writes, that your way is not hidden from God, for his might is matched by his tenderness. Unlike us, he never grows weary or tired; his empathy and understanding of our human frailties knows no boundaries. Isaiah acknowledges that you might be weary and weak, tired and faint, that even vigorous youth sometime struggle, stumble, and fall, "but those who hope in the Lord will renew their strength."

A few months ago I started reading at some length in the desert monastics of fourth century Egypt. Given that these oddball saints are so far removed from our own time, place, culture, and even (or especially) our practice of the Christian life, I kept wondering what drew me to them other than historical curiosity. A thousand pages later I realized that I loved them for what John Chryssavgis calls their "spirituality of imperfection." If society's holy grail of perfection—moral, spiritual, financial, physical, psychological, familial, vocational, whatever—is ultimately the "voice of the oppressor" (Anne Lamott), and I believe that it is, then these desert eccentrics pointed me to the liberating way of embracing brokenness without shame or embarrassment—my own, my mother's, or even the world's. They told stories that explained myself to myself.

Saint Anthony the Great, 16th century Russian icon. |

The early ascetics fled the corruption of church and society to seek Christ in the lonely solitude of the remote desert. If you have spent any time in a real desert, and I have, you can imagine the intensity and severity of their chosen orientation. Sometimes they lived in communities, while others chose "open combat" as solitary hermits. They sought what John Cassian (360–430) called "integrity of heart" or "integral wholeness." Seeking personal transformation and not mere theological information, they favored the voice of experience over theoretical claims, and human healing over book learning. But the conclusions of their spiritual experiment are not what you might expect.

With a fascinating mixture of remarkable candor, brutal realism, unqualified empathy, and wry humor, they describe how they experienced in the vast nothingness of the Egyptian desert a cacophony of voices in the interior geography of the heart. They sought wholeness but discovered brokenness. In the famous words of Saint Anthony the Great (251–356), the father of monasticism, they advised that we should "expect trials until your last breath." Their reports from the front lines of spiritual battle reveal a disarming transparency, "without any obfuscating embarrassment," and that never "despises anyone in belittling fashion" for human failure and frailty. As I review what I underlined in Cassian's Institutes and Conferences, for example, here is a sampling of their self-diagnosis—lethargy, sleeplessness, unsettling dreams, impulsive urges, self-justification, seething emotions, sexual fantasies, pious pretense that masked as virtue, self-deception, clerical ambition and the desire to dominate, crushing despair, confusion, wild mood swings, flattery, and the dreaded "noonday demon" of acedia ("a wearied or anxious heart" that suggests close parallels to clinical depression). As if that were not sufficiently unnerving, Cassian further admits that "there are [also] many things that lie hidden in my conscience which are known and manifest to God, even though they may be unknown and obscure to me."

|

Mother Syncletica. |

He wondered, for example, why a monk who joyfully renounced great wealth later succumbed to intense possessiveness or irascibility over a tiny pen knife, needle, book, or pen. He observed monks giving each other the "silent treatment." What provoked a brother's anger at a dull stylus? Or consider his description of a church service that included "spitting, coughing or clearing our throat or laughing or yawning or falling asleep." Or why is it, Cassian's friend Germanus asked his elder, "that superfluous thoughts insinuate themselves into us so subtly and hiddenly when we do not even want them, and indeed do not even know of them, that it is very difficult not only to cast them out but even to understand them and to catch hold of them?" Where, in other words, was the off-switch for a psyche in overdrive?

Despite their unrelenting realism about human foibles, the desert mothers and fathers did not live like helpless or hopeless victims. Far from it. They exuded confidence in God's unconditional love, exhibited tenderness and patience toward one another and to their own selves, steadfastly avoided the faintest hint of judgementalism, rejected every manifestation of extremist zeal, and chose not to compare themselves with others or even to be overly anxious about their progress. They believed that we can make genuine progress through vigilance and trust in God's grace, even though, paradoxically, the more you mature the wiser you become regarding your own fault lines. "We are," concluded Cassian, not angels but "only human beings." So, advises Mother Syncletica (died c. 400), "we sail on in darkness," confident in Isaiah's reminder that our way is never hidden from a God who is infinite in his understanding and unconditional in his love.

[Note: My mother died on January 21 after I wrote this essay. She was 83.]

For further reflection:

* In what sense do you agree or disagree with Lamott that "perfection is the voice of the oppressor?"

* Consider the ways we often deal with imperfections—denial, shame, blame, judgementalism, self-justification, pious cliches.

* Contemplate the "saying" of Saint Anthony: "Expect trials until your last breath."

* Why do Christians sometimes "shoot their wounded?"

* For further reflection: John Chryssavgis, In the Heart of the Desert; The Spirituality of the Desert Fathers and Mothers.