Life and Light, Death and Darkness

Lent 4B

For Sunday March 26, 2006

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year B)

Numbers 21:4–9

Psalm 107:1–3, 17–22

Ephesians 2:1–10

John 3:14–21

|

In the Academy Award's 2005 film of the year Crash, director Paul Haggis paints a grim picture of human nature. The movie opens with a car wreck that serves as a metaphor for the collisions between ordinary people that unleash the rage that is normally suppressed by superficial social bonds. The most incidental encounters can trigger this rage—vernacular slang, work, dress, music, marriage and family. We watch as a Persian shop keeper ("They think we're Arabs!"), a Hispanic locksmith, two black hoodlums, a wealthy black film director, redneck white trash, a despicable suburban white couple, and an idealistic white rookie cop project their insecurities and stereotypes onto each other. Paranoia—not all of which is unjustified, bigotry, and mutual misunderstanding darken their lives. In Crash good people are bad, bad people are good, and everyone is a mixture of the two. When he issues a simple traffic citation, officer Ryan (played by Matt Dillon) molests a woman in front of her husband, then in a twist of irony he later rescues her from a burning vehicle with professionalism, bravery and genuine compassion. In another scene he screams at a black woman clerk, while at home he tenderly cares for his dying father. "You think you know who you are," Ryan advises his rookie partner, "but just wait a few years."

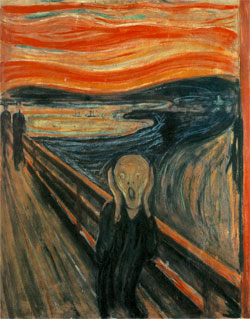

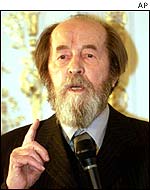

Other artists paint similar pictures. In The Scream (1893), the Norwegian painter Edvard Munch (1863–1944) evoked the anguish, isolation and fear that many people experience. In literature, after ten years of imprisonment and internal exile, then twenty years of banishment to Europe and Vermont after he was stripped of his citizenship for exposing the Soviet penal system in his three-volume Gulag Archipelago, Alexander Solzhenitsyn (b. 1918) concluded, "When I lay there on rotting prison straw...it was disclosed to me that the line separating good and evil passes not through states, nor between classes, nor between political parties either—but right through every human heart—and through all human hearts. This line shifts. Inside us, it oscillates with the years. And even within hearts overwhelmed by evil, one small bridgehead of good is retained. And even in the best of all hearts, there remains...an un-uprooted small corner of evil."

|

The Scream by Edvard Munch (1893) |

In John's Gospel Jesus invokes the metaphors of light and darkness to depict our human struggle, and, as counter-intuitive as it might seem, he observes how we sometimes even hate the former and love the latter. Similarly, in his letter to the Ephesians, Paul describes our human condition as a titanic struggle between forces of life and death. Ignoring our own best interests, he writes, we gratify our selfish cravings, follow dark desires, and relish irrational thoughts. This includes, he tells the Ephesians, "all of us."

We read about the moral monsters in history books (Hitler, Stalin, Lenin, Mao, Pol Pot, Idi Amin, et al.). The daily newspaper chronicles our will to death and darkness—political corruption, violence as media entertainment, corporate greed, beheadings in God's name, and a failed war that has slaughtered tens of thousands of human beings precious to God, squandered $250 billion, and demonstrated just how lethal dissimulation, hubris and stupidity can be. For the garden variety struggles of sickness, death, divorce, drugs, joblessness, and the like, cast a compassionate glance toward your colleague or neighbor.

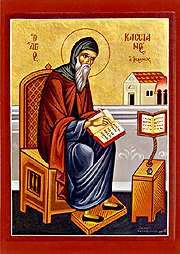

I am fascinated how even our best and brightest describe their experiences of fallenness. After a lifetime pursuing moral virtue among monastic communities, in his Conferences John Cassian (c. 360–435) wondered why monks who had renounced great wealth exhibited possessiveness over a needle, book or pen knife, or why a colleague flew into a rage at a dull stylus. In a remarkable anticipation of modern theories of the subconscious, he also admitted the "many things that lie hidden in my conscience which are known and manifest to God, even though they may be unknown and obscure to me."

|

Alexander Solzhenitsyn. |

Theories abound about how or why humanity arrived at this tug-of-war between light and life, death and darkness. Take your choice—bad genes, foolish choices, moral complacency, evolutionary struggle, vagaries of fate, family of origin, bad luck, inexplicable mystery, or primordial disobedience by our forbears that we inherited. I vote for "all of the above." But even if satisfying explanations of the cause of our sickness remain elusive, the experiential descriptions of their effects by people like Haggis, Munch, Solzhenitsyn, and Cassian ring true to me: "The fault is not in our stars," Cassius insisted to Brutus, "but in ourselves."

In an article in the Times Literary Supplement (February 24, 2006), the British Jewish novelist and playwright Gabriel Josipovici (b. 1940) argues that, much to our frustration, the Bible leaves many questions unanswered. As "pure narrative," he says, the Bible favors brutal realism about our human condition over superficial consolation or theological explanations: "It does so, it seems to me, because it recognizes that in the end the only thing that can truly heal and console us is not the voice of consolation but the voice of reality. That is the way the world is, it says, neither fair nor equitable. What are you going to do about it? How are you going to live so as to be contented and fulfilled?"

Lent teaches us that the road to Easter resurrection and consolation passes through repentance and confession of all that we have done in thought, word, and deed, sins of omission as well as sins of commission. Denial, passive neglect, scape-goating, or rationalizations on our part will only delay the healing process. The shame-n-blame that church, society, family and even our closest loved ones can pile on us can also hamper us. While some contemporaries might dismiss confession as overly dour, pessimistic, or even misanthropic, I believe with Josipovici that candid realism is in fact liberating, and with Cassian, who had surely seen and heard every sort of pious pretense, that embracing our brokenness "without any obfuscating embarrassment" is healing.

|

John Cassian. |

Because of God's character no person need fear death, either spiritual death now or physical death later. No one needs to grope in darkness. Every person can enjoy not merely bios or length of days but what Jesus calls "eternal" life and the Hebrew Bible calls shalom, genuine human wholeness. "God," writes John in his gospel, "did not send his Son into the world to condemn the world, but to save the world through him." Others might condemn you, but God does not. Paul agrees. After diagnosing our condition, he emphasizes that God showers us with great love, rich mercy, kindness, and incomparably rich grace, that is, with his unmerited favor. In being so favorably disposed to us, God longs to breathe life into the dead and to shine light into our darkness. Jesus compares this to a new birth. Just as every person has experienced an earthly birth of human origin, he invites us to experience a spiritual birth of divine origin.

Having confessed the depth of our need, we have only to embrace the grace God offers us. Paul tells the Ephesians that we do this by faith alone, apart from any human merit, extending toward God what Luther described as "the beggar's empty hand" to receive his gift. Accepting that we are accepted, just as we are and where we are, by Him whose love far exceeds human failure, Lenten sorrow anticipates Easter joy and gratitude.

For further reflection:

* What do you make of the descriptions of our human condition made by Haggis, Munch, Solzhenitsyn, and Cassian?

* Do you find these descriptions overly negative and pessimistic, or realistic?

* Why is it so hard to admit our faults, sins, and failures?

* How much health, healing, and wholeness might we expect this side of heaven?