The Divided Loyalties of Resident Aliens

Strange Lands Your Home, Your Home a Strange Land

For Sunday April 30, 2006

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year B)

Acts 3:12–19

Psalm 4

1 John 3:1–7

Luke 24:36b–48

|

Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf of Liberia. |

A few weeks ago I bought a plane ticket to Liberia to attend an HIV workshop with Global Strategies for HIV Prevention. From a human perspective Liberia is a failed state that the Economist identified as the single worst place in the world to live in 2003. Life expectancy at birth is 39 years, literacy hovers at 50% (40% for women), and unemployment is 80%. Since 1980 civil wars under the despotic regimes of Samuel Doe and Charles Taylor slaughtered over 200,000 citizens and displaced another one million (out of a population of 3 million). In January 2006 Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf was inaugurated as the first freely elected woman head of state in the history of Africa, bringing at least a glimmer of hope to a dispossessed people.

That's the human perspective. But according to the Scriptures for this week Liberia is as important to God, as loved by God, and as central to his purposes as any place on earth, despite what the Economist says. We don't actually believe that, of course, but that's the Christian perspective. And if you believe that God's favor bends toward the oppressed, the marginal, and the exploited, then, paradoxically, Liberia is high on God's list even though it is low on ours: "The last will be first, and the first will be last" (Matthew 20:16). Which is a good reason to travel to Monrovia.

|

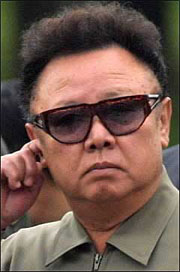

Kim Il Jong of North Korea. |

After his resurrection Jesus told his followers to spread his message "to all nations, beginning at Jerusalem" (Luke 24:48; cf. Matthew 28:19). In his parallel passage Mark renders the meaning more emphatic by writing "all creation" (Mark 16:15). Similarly, in Luke's sequel to his gospel Jesus told his timid followers, "you will be my witnesses in Jerusalem, and in all Judea and Samaria, and to the ends of the earth" (Acts 1:8). Finally, in the lectionary for this week, Peter concludes his sermon by proclaiming that in Jesus "all peoples on earth will be blessed" by God (Acts 3:25 = Genesis 22:18, 26:4), which global promise was first made to Abraham 4,000 years ago (Genesis 12:3).

A few decades later John wrote from the Greek island of Patmos where he had been banished to political exile, and offered his own version of the globalization theme. He dreamed that such a global gathering would be fulfilled beyond history. He envisioned heaven populated with people from "every nation, tribe, people, and language" (Revelation 7:9). Today, John's vision of a globalized heaven beyond history has already been fulfilled on earth in history. Starting with a few uneducated, bedraggled and timid disciples, today about a third of the world identifies itself as Christian, nearly twice as many as those who follow Islam or Hinduism (roughly one billion each). Christians from 200 countries have accessed this webzine, to take but one tiny data point.

|

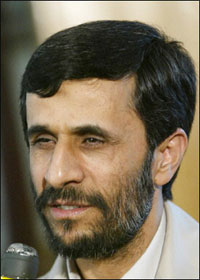

Iran's Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. |

Two radical corollaries follow from this robustly Christian global vision—the decentralization of your geography and the reorientation of your politics.

First, Christians are geographic, cultural, national and ethnic egalitarians; for them there is no geographic center of the world, but only a constellation of points equidistant from the heart of God. Proclaiming that God lavishly loves all the world, each person, and every place, the Gospel does not privilege any country as exceptional. For example, much has been written lately about American exceptionalism and our current global hegemony. In terms of economic, political, military, scientific and cultural dominance, America is unrivaled, and in that sense "exceptional" (although there is no reason to think that will last forever). But from a theological or Christian point of view America is no more "exceptional" in God's eyes than any other country. While allowing for a natural and wholesome love, even pride, in your own country ("there's no place like home"), ultimately geo-political egalitarianism subverts the claim of absolute allegiance to any one nation. Your ultimate citizenship, said Paul, is a spiritual one (Philippians 3:20).

|

President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo, Philippines. |

Second, because of this, Christian global vision asks that you care as much about any and every country and its people as you do your own. Christians grieve the deaths of 35,000 Iraqis as much as 2,300 Americans, or lament the human tragedy of the Iranian and Pakistani earthquakes as much as that of Hurricane Katrina. This implies that your politics become reoriented, non-aligned, and unpredictable by normal canons. In his new book What Jesus Meant (2006) Garry Wills argues that there is no such thing as a "Christian" politics, and that efforts by both Democrats and Republicans to co-opt him for their side badly distort the Jesus of the Gospels. The Jesus of the Gospels proposes no political program, but something far more strenuous, something "scary, dark and demanding." No state or political party, says Wills, can indulge in the self-sacrifice that Jesus demands when he asks his followers to lovingly serve the least and the last wherever they live.1

About a generation after John wrote, an early work called the Letter to Diognetus (c. 130 AD) captured this ambivalent relationship between the believer's geo-political identity and Christian confession (5:1–5, my emphasis).

For the Christians are distinguished from other men neither by country, nor language, nor the customs which they observe. For they neither inhabit cities of their own, nor employ a peculiar form of speech, nor lead a life which is marked out by any singularity. The course of conduct which they follow has not been devised by any speculation or deliberation of inquisitive men; nor do they, like some, proclaim themselves the advocates of any merely human doctrines. But, inhabiting Greek as well as barbarian cities, according as the lot of each of them has determined, and following the customs of the natives in respect to clothing, food, and the rest of their ordinary conduct, they display to us their wonderful and confessedly striking method of life. They dwell in their own countries, but simply as sojourners [or resident aliens]. As citizens, they share in all things with others, and yet endure all things as if foreigners. Every foreign land is to them as their native country, and every land of their birth as a land of strangers.

|

Prime Minister Begum Khaleda Zia, Bangladesh. |

Like all people, Christians reflect whatever time and place they live. We support and enjoy our various countries, but as if we were resident aliens. We experience an ambivalent and divided loyalty—ultimate loyalty only to the city of God and its "politics" of self-sacrificing love, and merely penultimate loyalty to the city of man and to what Diognetus called its "merely human doctrines." We honor "every foreign land" as if it were our own, and experience our own countries as a "foreign land." By some miracle of grace I hope to find myself at home in Liberia and ill at ease in America, not because either is better or worse than the other, but because both are equally loved by God.

For further reflection:

* How do you understand the relationship between Christian and geo-political identities?

* What distinguishes a legitimate love of country from misplaced nationalist zeal?

* Reflect on Philippians 3:20: "Our citizenship is in heaven."

* What do you think the quotation from the Letter to Diognetus means?

* See Garry Wills, What Jesus Meant (2006).

[1] For a short version of Wills' argument see his New York Times Op-Ed, "Christ Among the Partisans," April 9, 2006. Wills is only partly right about Jesus because (1) some moral demands of Jesus have significant political ramifications, and some political choices have moral consequences.