Judas and Matthias:

On Mystery and Destiny

For Sunday May 28, 2006

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year B)

Acts 1:15–17, 21–26

Psalm 1

1 John 5:9–13

John 17:6–19

|

In the remarkable film Capote (2005), Truman Capote (1924–1984) befriends a murderer named Perry Smith in order to research his "non-fiction novel" In Cold Blood. Although he gave some legal help to Smith, he ultimately exploited him for fame and fortune. He fretted to his childhood friend Harper Lee, for example, that he actually needed Perry to die in order to finish his book: "If they win this appeal, I may have a complete nervous breakdown." He repeatedly lied to Smith about his book's progress, manipulated him for details, betrayed him to legal limbo, and when asked by Lee if he "esteemed" Smith, could only say, "well, he's a gold mine."

Interviewing Smith also dislodged unsettling memories of Capote's own childhood—memories of exclusion as an effeminate kid, family suicide, alcoholism, and parental abandonment. These haunting memories fueled an obsessive act of self-identification with and emotional attachment to Smith, so much so that his gay parter Jack Dunphy accused him of falling in love with Perry. But despite their dysfunctional childhoods, their life trajectories could hardly have been more different. Capote became an icon of New York City's rich and famous glitterati, and died of alcohol and drug abuse at the age of sixty. Smith was a poor, obscure petty criminal and merciless killer who was executed by the state of Kansas when he was thirty-six. Capote pondered this mystery of fate in diverse destinies that unfolded from similar beginnings: "It's like Perry and I grew up in the same house, and one day he stood up and went out the back door, and I went out the front."

|

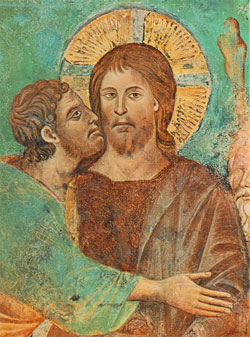

14th century illuminated mss. of Judas. From http://sunsite.berkeley.edu/scriptorium. |

The reading from Acts this week introduces two men, both of whom served in the inner circle of Jesus's twelve apostles. For people across many cultures and twenty centuries the name Judas Iscariot has epitomized infamy, treachery, and tragedy. As for Matthias, despite his importance as the "thirteenth apostle" who replaced Judas, history consigned him to anonymity and obscurity. Since Acts 1:12–26 is the only passage about Matthias in Scripture, we know virtually nothing about him. As I meditate on the lives of these two intimate followers of Jesus, I find it difficult if not impossible to understand how or why each one ended up where he did. Such is the mystery of destiny, both theirs and ours.

|

Judas. |

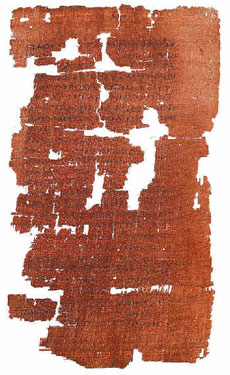

With his infamous kiss of betrayal Judas "served as a guide for those who arrested Jesus" (Acts 1:16). But why? How could he have commited such a deplorable act? Three Scriptures locate the explanation outside of and beyond Judas's own choices. John's gospel this week says that Judas was "doomed to destruction" (John 17:12), as if some ominous fate overtook him. John and Luke also say that Judas's betrayal "fullfilled Scripture" (John 17:12, Acts 1:16); but their interpretation of the Old Testament to reach this New Testament conclusion is one that would make most hermeneutics professors scratch their heads. Luke also writes that “satan entered Judas” to betray Jesus (Luke 22:3). I don't find any of these explanations satisfying or illuminating. Still, at a fourth level we should not patronize Judas as a mere pawn. He did what he did for his own complex motives, some of which are no doubt lost to us today. He received his famous "thirty pieces of silver," but I suspect that other factors came into play, including some that he himself could not fathom. Perhaps it was natural when 150 years later some fringe gnostic Christians tried to rehabilitate Judas's reputation. The recently discovered Gospel of Judas—a third or fourth century Coptic translation from the original Greek that contains very little that is specifically Christian—portrays Judas as a hero who betrays Jesus at his own request, and not as the quintessential villain.

As for his own convoluted motives and their tragic outcome, we can say three things. First, in itself Judas's betrayal of Jesus is unremarkable. Peter denied that he would ever betray the Lord, but did so three times. The other eleven all said the same thing, but when Jesus was arrested all the disciples deserted him and fled (Matthew 26:56) We should never deny our capacity for denial. Second, after betrayal and denial, Judas and Peter responded in similar ways. After aiding and abetting in the condemnation of Jesus, Judas was “filled with remorse” and returned the blood money. Finally, in playing the most undesireable role in all of human history, in some sense Judas took our place and triggered the events that lead to the greatest good for all humanity, the death and resurrection of Jesus.

|

4th century Coptic Gospel of Judas. |

The selection of Matthias to replace Judas is no less murky. Peter invokes Psalm 109:8 to validate the process with the imprimatur of prophetic fulfillment: "May another take his place of leadership." At a more mundane level the eleven remaining apostles simply nominated two candidates: "they proposed two men" (Acts 1:23). When they prayed they confessed that God himself had already chosen the right person, and that their task was to decipher the divine predetermination. Finally, and I have always wondered if any church committee has ever dared to use this method, the apostles resorted to "dumb luck" to ascertain the divine intent (Beardslee in Pelikan, Acts)—a roll of the dice identified Matthias instead of the alternate "Joseph called Barsabbas."

Contemplating these mysteries of personal destiny, my mind has returned time and again to a poem by John Milton (1608–1674), perhaps the greatest poet of the English language. Struck blind at the age forty-four, in his poem When I Consider How My Light Is Spent Milton ponders why God would gift him with remarkable talents only to take them back. The ways of God felt harsh and arbitrary: "Doth God exact day-labor, light denied?" Plunged into a world of darkness, he wondered:

When I consider how my light is spent,

Ere half my days in this dark world and wide,

And that one talent which is death to hide

Lodged with me useless, though my soul more bent

To serve therewith my Maker, and present

My true account, lest He returning chide;

"Doth God exact day-labor, light denied?"

I fondly ask. But Patience, to prevent

That murmur, soon replies, "God doth not need

Either man's work or His own gifts. Who best

Bear His mild yoke, they serve Him best. His state

Is kingly: thousands at His bidding speed,

And post o'er land and ocean without rest;

They also serve who only stand and wait."

Patience, humility, availability, and even resignation to the inscrutabilities of divine designs all serve us well. In the words of Milton's near contemporary George Herbert (1593–1633), it's probably best to "leave thy cold dispute/about what is fit or not" (The Collar). Whoever we are and wherever we are—a haunted novelist, a failed disciple, an obscure apostle, or a struggling poet—every person can "serve Him best" right where they are, even those "who only stand and wait."

For further reflection:

* What do you think of when you consider Judas?

* What do you take from Milton's poem?

* Have you ever had to "only stand and wait" when you wanted to "speed and post o'er land and ocean without rest?"

* See The Gospel According to Judas: Is There a Limit to God's Forgiveness? by Ray S. Anderson.