Little Children and God's Kingdom:

The Holy Grail of Human Greatness

For Sunday September 24, 2006

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year B)

Proverbs 31:10–31 or Wisdom of Solomon 1:16–2:1, 12–22 or Jeremiah 11:18–20

Psalm 1 or Psalm 54

James 3:13–4:3, 7–8

Mark 9:30–37

As a campus minister with InterVarsity at Stanford, in the fall of 1997 we piloted a "faculty fellowship" specifically for professors. About a dozen faculty began a breakfast meeting every Friday morning from 7–8am in the faculty club. A year later a Tuesday morning group started in the Bing Dining Room at the hospital for medical faculty and physicians, then a few years later a Thursday group emerged at Stanford's linear accelerator for the physics crowd. We began with little idea whether the idea would work, much less flourish, but across the next six years perhaps a hundred professors, research fellows, lecturers, physicists, and visiting faculty joined us at one time or another.

|

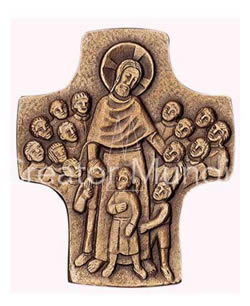

Who's the Greatest? by SZ Richardson. |

When we started most people did not know each other, so every Friday a different professor shared his or her Christian story. The very first Friday morning Doug disarmed everyone with a candid account of his disintegrating marriage. The following week Tony related his frustrations with raising teenagers. Another recounted his financial failures. In the succeeding months it became clear that these remarkably gifted people who had reached the pinnacle of professional success were more interested in sharing their lives rather than mere ideas. The group took on a distinctly pastoral rather than academic ethos. How do you balance personal and professional responsibilities? How do spouses negotiate dual careers with heavy demands? What advice might an older professor give to a younger scholar facing the tenure process? Does God care about my neuroscience research? I still remember the morning that Chuck spoke for many of those exceptionally gifted and gracious professors when he noted with his trademark sardonic wit that "behind every great man there often lies a trail of human wreckage."

Given a safe space that offered Christian encouragement, the Stanford professors experienced the message of Jesus that Mark articulates in his Gospel this week, namely, that the holy grail of human greatness that we so honor, envy and pursue—rank, wealth, recognition, power, title, privilege, and prestige—can exact a very high personal price. Worldly greatness has a limited capacity to nourish authentic human fulfillment, it does not protect us from human vulnerabilities, and it often prevents us from experiencing God's kingdom. To make this point, by his words and actions Jesus radically reversed our normal ideas about greatness and taught that insignificant children epitomize the ethos of his kingdom.

|

Christ sets a child before the disciples. |

Three different times in Mark's Gospel Jesus warned his twelve disciples about the end game that awaited him in Jerusalem—betrayal, condemnation, suffering, rejection, violent death, and resurrection. All three times the disciples responded to Jesus with objections, disbelief, fear, and ignorance, demonstrating just how badly they misunderstood the true nature of his redemptive mission. After his first "passion prediction," Jesus rebuked Peter for trying to prevent his sufferings: "You do not have in mind the things of God but the things of man" (Mark 9:33). After the third prediction, James and John asked Jesus for positions of glory, whereupon the other ten indignantly objected, clearly worried that James and John might gain some advantage over them. After the second prediction (the Gospel for this week), the disciples argued among themselves about who was the greatest (Mark 9:34). Whereas in predicting his death Jesus signaled that his kingdom was characterized by self-sacrificial service for others, the disciples jockeyed for human glory and greatness.

|

Jesus responded to his disciples in two ways. First, he gave them a teaching: "Calling the Twelve to himself, Jesus said, 'If anyone wants to be first, he must be the very last, and the servant of all'" (9:35). Second, Jesus enacted or dramatized a parable. He placed a little child before the disciples, then took the child into his arms and said, "Whoever welcomes one of these children in my name welcomes me; and whoever welcomes me does not welcome me but the one who sent me" (9:37). In Matthew's parallel account of the same passage Jesus says, "unless you change and become like little children, you will never enter the kingdom of heaven (Matthew 18:3). Just one page later in Mark's Gospel the disciples rebuked people who brought little children to Jesus so that he would bless them. "When Jesus saw this, he was indignant. He said to them, 'Let the little children come to me, and do not hinder them, for the kingdom of God belongs to such as these. I tell you the truth, anyone who will not receive the kingdom of God like a little child will never enter it'" (10:13–16).

To welcome a child is to extend the simplest of acts to an individual that society normally dismisses as perhaps cute but ultimately insignificant, someone who entirely lacks any accomplishments, greatness, status, or pretensions. By extension, Jesus invites us to welcome every person in the same manner, without regard for external measures of their worldly importance, status, success or failure. Lately I have tried the following experiment. Whenever I am repulsed by a homeless bum who loiters near our home, or nurse a grudge against a friend who spurned me, or envy someone more successful than I am, I try to picture that person as a little baby or child. I then find it far easier to welcome or receive them only as a precious human being, rather than someone who can help or harm me, as someone I might ignore, fear or flatter. The simple act of welcoming another person in that way, Jesus says, is to welcome him, and in turn to welcome God the Father who sent him. Similarly, to become or imitate children, as Jesus commands, is to understand our own selves in the same manner, not as people whose significance rests in titles, honors, successes or failures, as if those might gain or deny us favor with God and man, but in the knowledge that we are human beings loved by God. That, says Jesus, is the only way to experience the presence of his kingdom.

|

Jesus blesses the children. |

After eight and a half years with InterVarsity at Stanford I needed my own safe place where I could be welcomed like a little child. I discovered that place when I volunteered for our church nursery. Except for my daughter's soccer games and my travel, every Sunday for two years my wife and I served in the "Lambs" Sunday school class for babies three to twelve months old. My failures and successes, my importance or lack thereof as the world (and Christians!) judged it, did not matter to little babies. My PhD didn't cut any ice with overweening parents, a few of whom grew visibly apprehensive when they saw a man in the nursery. My mentors, Evelyn in her seventies and Miriam in her eighties, taught me lots about generous compassion as they comforted crying babies, assured anxious parents, changed dirty diapers, and without fanfare welcomed hundreds of children across many decades. They taught me as much about entering the kingdom that Jesus announced as my faculty friends at Stanford.

For further reflection:

* What would our lives look like if we really believed and acted on these words of Jesus?

* Consider the disciples's chronic and deep misunderstanding about the true nature of God's kingdom.

* How do children constitute a counter-intuitive and subversive example of greatness?

* Based upon these words of Jesus, who is really making history?

* See Henri Nouwen, The Road to Daybreak and Adam: God's Beloved. Nouwen was a Dutch Catholic priest and the author of forty books. He left his Harvard professorship to become a priest in a residential home for the mentally and physically handicapped called L'Arche near Toronto. He died in 1996.