The Coming of the Son of Man:

Disbelief, Voyeuristic Violence, or Future Redemption?

For Sunday December 3, 2006

First Sunday in Advent

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

Jeremiah 33:14–16

Psalm 25:1–10

1 Thessalonians 3:9–13

Luke 21:25–36

|

Jeremiah, anonymous, c. 1120. |

Next Sunday Christians around the world begin the season of Advent, a time when we commemorate the adventus of Jesus—his coming, arrival, or birth into our world. Some time around the sixth century the tradition emerged to set aside four weeks before Christmas, beginning with the Sunday closest to Saint Andrew's Day (November 30), as a period to look both backwards and forwards.

Believers look backwards in celebration of the birth of Jesus, to that time and place when we believe that "God was in Christ, reconciling the cosmos to himself" (2 Corinthians 5:19). In her poem On the Mystery of the Incarnation, Denise Levertov (1923–1997), whose father was a Hasidic Jew who converted to Christianity and then became an Anglican pastor, captures the miracle of this "first coming" of Jesus:

It's when we face for a moment

the worst our kind can do, and shudder to know

the taint in our own selves, that awe

cracks the mind's shell and enters the heart:

not to a flower, not to a dolphin,

to no innocent form

but to this creature vainly sure

it and no other is god-like, God

(out of compassion for our ugly

failure to evolve) entrusts,

as guest, as brother,

the Word.

At Advent Christians also look forward in expectation to Christ's coming again, to that time when we believe that God will culminate what He has now only inaugurated, when He will finish what He has started, and will fulfill what He has promised. Three of the four lectionary readings this week speak of a future restoration or consummation of human history (only Psalm 25 does not). Future restoration in a messianic age and a "second coming" are prominent themes deeply embedded in the Hebrew Old Testament, the Christian New Testament, and the earliest Christian creeds.

Celebrating Christmas and the past history of the incarnation at Bethlehem seems easy enough; but how should we speak about expectation and anticipation of the future fulfillment of history? Unbelievers respond to scenarios of the "end times" with disbelief and derision, while Christians can cloud the picture with sensationalism, date-setting, and fictional novels characterized by what Barbara Rossing calls "voyeuristic violence" (cf. the Left Behind series that has sold over 60 million books).

I don't find the disbelief of atheists like Richard Dawkins and Sam Harris unsettling or compelling. Every person can be certain about some "end time" scenarios. I've come to think of the end of history in four ways.

|

Jeremiah, by Duccio di Buoninsegna, 1308-1311. |

If you are a man living in Liberia, your life expectancy at birth is 39 years. If you are lucky enough to be born a woman in Japan, then you can expect to live 84.7 years. Then comes your personal end, and whether late or soon, it will surely come. Environmental experts like Jared Diamond (Collapse) speak of civilizational (or cultural) death. His case studies show how some very advanced civilizations have vanished. Without major course corrections, many social-scientific studies like the UN's State of the World Population predict apocalyptic scenarios due to nuclear weapons, global warming, population growth in the places that can least sustain it, over-consumption of limited fossil fuels, massive economic inequalities, large scale displacements of populations, famines, and wars. It would be foolish to think that our own civilization will last forever. The earth's end is just as certain, but will take longer. My friend and solar physicist Charles says that in about 5 billion years the sun will expand to 10,000,000 times its present volume, a red giant that will incinerate and eventually swallow the Earth. Fourth, as for the cosmic end of the entire universe, physicists are divided, but equally bleak. If the expansion of the Big Bang continues to propel everything outward, our galaxies will fly apart forever, although individual galaxies will collapse into black holes. But if the forces of gravity prevail, the expanding universe will eventually reverse its expansion and collapse into a Big Crunch. "It is as sure as can be," writes the physicist and Anglican priest John Polkinghorne, "that humanity, and all forms of carbon-based life, will prove a transient episode in the history of the cosmos."

So, several "ends" await us—personal, civilizational, global and cosmic. But then what? What comes after the end? No one knows, or even can know. Any position you take constitutes an act of faith. In his review of The God Delusion by Richard Dawkins, Jim Holt thus observes that "short of a miraculous occurrence, the only thing that might resolve the matter is an experience beyond the grave—what theologians used to call, rather pompously, 'eschatological verification.' If the after-death options are either a beatific vision (God) or oblivion (no God), then it is poignant to think that believers will never discover that they are wrong, whereas Dawkins and fellow atheists will never discover that they are right."1

Rossing suggests that what ends at "the end" is not the earth or the cosmos, which God created, loves, and will redeem (cf. Romans 8:18–27), but the oikoumene, which she translates as the "imperial world" (cf. Revelation 3:10), that is, all the systems of domination, exploitation, and subjugation that so many peoples of the earth experience right now.2 This is precisely the sort of scenario that the prophet Jeremiah preached to Judah in the wake of national disaster and deportation to pagan Babylon in 586 BC. "The days are coming," he tells his people, when prosperity will replace calamity, when future restoration will overcome present desolation. That time, Jeremiah says, will be a time of health and healing, security and safety, abundant prosperity, joy, gladness, thanksgiving and forgiveness (Jeremiah 33). In the Gospel this week Jesus describes a day when "redemption draws near" for "the whole earth" (Luke 21:28, 35).

We need not know the details of the "last days" or "second coming" described by Jeremiah, Jesus or Paul. I like CS Lewis's analogy of actors in a very real drama. We don't know everything about the play, whether we're in the first or last act, or even which characters play the minor and major roles. In our ignorance, we really have no idea when the End of the play ought to come. But the plot will find fulfillment, even if our limited understanding right now obscures it. Perhaps the Author will fill us in after it is over, but for now, "playing it well is what matters infinitely."

|

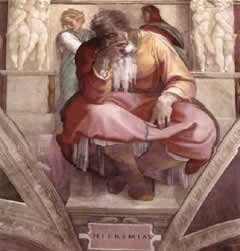

Jeremiah, by Michaelangelo, Sistine Chapel, 1511. |

And so in Luke's Gospel this week Jesus exhorts his followers to "play it well." He warns us that just as we know that summer is near when certain flowers bloom, we should not let the anxieties of life weigh us down so that the end "closes on you unexpected like a trap." Rather, he tells us to live carefully, to watch, and to pray that we "may be able to stand before the Son of Man" (Luke 21:34–36).

For further reflection

* Why do you think pot-boiler fiction like the Left Behind books are so wildly successful?

* What has been your experience of Christian "end times" teaching?

* How do you think history might end? See Romans 8:18–27.

* Cf. Barbara Rossing, The Rapture Exposed: The Message of Hope in the Book of Revelation (2004).

[1] New York Times, October 22, 2006.

[2] "End Game," The Christian Century (November 14, 2006), pp. 22–25.