The Outrage of Outsiders:

Why So Many People Dislike Christians

For Sunday January 20, 2008

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year A)

Isaiah 49:1–7

Psalm 40:1–11

1 Corinthians 1:1–9

John 1:29–42

|

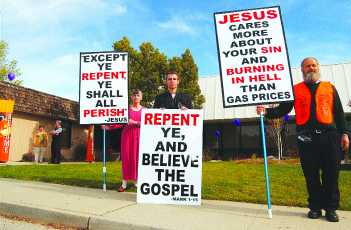

Christians at the funeral of Matthew Shepard, October 16, 1998. |

In his book The Heart of Christianity (2003) Marcus Borg of Oregon State University describes how his university students have a uniformly negative image of Christianity. "When I ask them to write a short essay on their impression of Christianity," says Borg, "they consistently use five adjectives: Christians are literalistic, anti-intellectual, self-righteous, judgmental, and bigoted."

Christians might object, rather defensively, that it's unfair to draw sweeping conclusions based upon the report of one person. If you think that way, you'd be right in your logic but wrong in your conclusion. A new book called unChristian (2007) by David Kinnaman of the Barna Group presents objective research that supports Borg's subjective anecdote. Kinnaman's three-year study documents how an overwhelming percentage of sixteen to twenty-nine year olds view Christians with hostility, resentment and disdain.

These broadly and deeply negative views of Christians aren't just superficial stereotypes with no basis in reality, says Kinnaman. Nor are the critics people who've had no contact with churches or Christians. It would be a tragic mistake, he argues, for believers to protest that outsider outrage at Christians is a misperception. Rather, it's based upon their real experiences with today's Christians.

According to Kinnaman's Barna study, here are the percentages of people outside the church who think that the following words describe present-day Christianity:

* antihomosexual 91%

* judgmental 87%

* hypocritical 85%

* old-fashioned 78%

* too political 75%

* out of touch with reality 72%

* insensitive to others 70%

* boring 68%

It would be hard to overestimate, says Kinnaman, "how firmly people reject — and feel rejected by — Christians" (19). Or think about it this way, he suggests: "When you introduce yourself as a Christian to a friend, neighbor, or business associate who is an outsider, you might as well have it tattooed on your arm: antihomosexual, gay-hater, homophobic. I doubt you think of yourself in these terms, but that's what outsiders think of you" (93).

Gabe Lyons of the Fermi Project who commissioned the Barna research remembers his first look at the data. "I'll never forget sitting in Starbucks, poring through the research results on my laptop. As I soaked it in, I glanced at the people around me and was overwhelmed with the thought that this is what they think of me. It was a sobering thought to know that if I had stood up and announced myself as a 'Christian' to the customers assembled in Starbucks that day, they would have associated me with every one of the negative perceptions described in this book" (222, his italics).

So, Borg was right. Maybe even more right than he knew. But it wasn't always this way.

|

In John's gospel this week Jesus speaks for the first time. When Andrew and a friend asked Jesus where he was staying, Jesus said, "Come and see." And so they did, spending the whole day with Jesus. They were so taken by that one day with Jesus that "the first thing Andrew did," writes John, was to find his brother Peter and say: "Come and see." The very next day, John writes, Philip grabbed Nathaniel and said the same thing: "Come and see."

Thus were the unlikely beginnings of an improbable movement. The gospels record how throngs of people were so captivated by the preaching, teaching and healing of Jesus that they did, in fact, "come and see" for themselves. Based upon what they experienced with Jesus, their lives were radically re-oriented.

After his death and resurrection, the community that emerged of those who had been with Jesus gained a reputation the exact opposite of the one documented by Kinnaman. The first believers, says Luke, "enjoyed the favor of all the people" (Acts 2:47). "Great grace was with them all," Luke wrote (Acts 4:33).

The simple greeting of Paul's letter to the Corinthians in this week's epistle is also instructive. To that very troubled group of believers — sectarian divisions, boasting about incest ("and of a kind that does not occur even among pagans," 1 Corinthians 5:1), lawsuits between fellow Christians, eating food that had been sacrificed to pagan idols, disarray in worship services, and predatory pseudo-preachers masquerading as super-apostles — to these people Paul wholeheartedly wished "grace and peace." He said that he hoped they would be "enriched in every way" (1 Corinthians 1:3,4). He wished them only good. Consider what our world might be like if we each offered our neighbor a similar wish for their well-being.

Following the example of Jesus, the first Christians broke down social barriers. They disregarded religious taboos that judged people as ritually clean or unclean, worthy or unworthy, respectable or disrespectable. They subverted normal social hierarchies of wealth, ethnicity, religion, and gender in favor of a radical egalitarianism before God and with each other: "There is neither Jew nor Greek, slave nor free, male nor female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus" (Galatians 3:28).

In a word, the first believers were generous. They demonstrated authentic transparency, not moral superiority or ulterior motives. Like their Lord, they exuded compassion rather than condemnation. They lived out of gratitude not fear, and had a reputation for empathy rather than fault-finding. The first followers of Jesus were people of self-sacrifice, not self-interest. They insisted that God was like a tender father, not a vindictive tyrant, and encouraged every person without exception to believe what the psalmist said: "This I know, that God is for me" (Psalm 56:9).

|

A generation after the first believers, the theologian Justin Martyr (c. 100–165) summarized the appeal of Christian community: “Those who once delighted in fornication now embrace chastity alone. . . we who once took most pleasure in accumulating wealth and property now share with everyone in need; we who hated and killed one another and would not associate with men of different tribes because of their different customs now, since the coming of Christ, live familiarly with them and pray for our enemies.” Similarly, Tertullian (AD 155–220), who wrote, "Our care for the derelict and our active love have become our distinctive sign before the enemy. . . See, they say, how they love one another and how ready they are to die for each other."

I wish that we could somehow recapture the witness of those first believers who, because "great grace was with them all," demonstrated overflowing generosity to their neighbors, and who consequently "enjoyed the favor of all the people." I wish those traits could be what Tertullian called "our distinctive mark" instead of what most people today think of when they hear the word "Christian."

For further reflection:

* Cf. John: "If anyone says, 'I love God,' yet hates his brother, he is a liar. For anyone who does not love his brother, whom he has seen, cannot love God, whom he has not seen. And he has given us this command: Whoever loves God must also love his brother" (1 John 4:20–21).

* Cf. Saint Maximos the Confessor (580–662): "Blessed is the person who can love all people equally . . . always thinking good of everyone."

* Update Galatians 3:28 ("There is neither Jew nor Greek, slave nor free, male nor female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus.") with contemporary categories that divide people. "There is neither. . ."

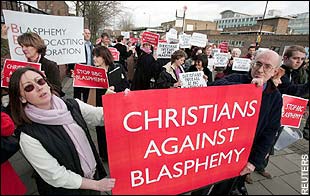

Image credits: (1) Syracuse University Magazine; (2) The Auburn Journal, November 14, 2005, Auburn, California; and (3) the www.telegraph.co.uk website for January 10, 2005.