The Parallel Universe of the Passion of Jesus

Palm Sunday or Passion Sunday

Sixth Sunday in Lent 2008

For Sunday March 16, 2008

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year A)

Isaiah 50:4–9a

Psalm 31:9–16

Philippians 2:5–11

Matthew 26:14–27:66 or Matthew 27:11–54

|

Jesus's Triumphal Entry, Medieval Syriac manuscript. |

Palm Sunday signaled the beginning of the end for Jesus.

Palm Sunday began with a festive procession. Good Friday ended with the death penalty. Excited children waving palm branches gave way to violent mobs shouting death threats. Adoration by the crowds in Jerusalem evaporated into abandonment by God on Golgotha.

Between Palm Sunday and Good Friday, Jesus's disciples argued among themselves about who was the greatest, Judas betrayed him and then committed suicide, Peter denied ever knowing him, and all his disciples fled for the high grass (except for the women). After three years of itinerant preaching, teaching, and healing that focused on the poor, the imprisoned, the blind, and all who were oppressed (Luke 4:18ff), Jesus's family declared him insane, the religious establishment hated him, and the political authorities had had enough. And so Rome deployed all the brutal means at its disposal to crush an insurgent movement—rendition, interrogation, torture, mockery, humiliation, and then a sadistic execution designed as a "calculated social deterrent" (Borg) to any other trouble makers who might challenge imperial authority and disturb the Pax Romana.

|

The Last Supper, 11th century Udabno monastery near Tblisi, Georgia. |

But why did Jesus die? The passion narratives for this week explain why.

Jesus was executed for three reasons, says Luke: "We found this fellow subverting the nation, opposing payment of taxes to Caesar, and saying that He Himself is Christ, a King" (Luke 23:1–2). In John's gospel the angry mob warned Pilate, "If you let this man go, you are no friend of Caesar. Anyone who claims to be a king opposes Caesar" (John 19:12).

In short, "He's subverting our nation. He opposes Caesar. You can't befriend both Jesus and Caesar." They were right, even more right than they knew or could have imagined.

Jesus's "triumphal entry" into the clogged streets of Jerusalem on Good Friday was a deeply ironic, highly symbolic, and deliberately provocative act. It was an enacted parable or street theater that dramatized his subversive mission and message. He didn't ride a donkey because he was too tired to walk or because he wanted a good view of the crowds. The Oxford scholar George Caird characterized Jesus's triumphal entry as more of a "planned political demonstration" than the religious celebration that we sentimentalize today.

|

The Condemnation of Christ and the Denial of Saint Peter , early fifth century, British Museum, London. |

Because the Roman state always made a show of force during the Jewish Passover when pilgrims thronged to Jerusalem to celebrate their political liberation from Egypt centuries earlier, Borg and Crossan imagine not one but two political processions entering Jerusalem that Friday morning in the spring of AD 30. In a bold parody of imperial politics, king Jesus descended the Mount of Olives into Jerusalem from the east in fulfillment of Zechariah's ancient prophecy: "Look, your king is coming to you, gentle and riding on a donkey, on a colt, the foal of a donkey" (Matthew 21:5 = Zechariah 9:9). From the west, the Roman governor Pilate entered Jerusalem with all the pomp of state power. Pilate's brigades showcased Rome's military might, power and glory. Jesus's triumphal entry, by stark contrast, was an anti-imperial and anti-triumphal "counter-procession" of peasants that proclaimed an alternate and subversive community that for three years he had called "the kingdom of God."

But what were Jesus and his first followers subverting?

For about a hundred years Christians were invisible to most people in the Roman empire. But across the decades they earned a reputation as an alternate and anti-social community that existed on the margins of the state. They were a people of the periphery—fanatical, seditious, obstinate, and defiant. Tacitus called them "haters of mankind." Some derided them as "atheists" because they refused to participate in Rome's cult of imperial worship. Others disparaged them as a "third race" that distinguished itself from the "first race" (Greeks and Romans) and the "second race" (Jews).

|

Mosaic of Christ before Pilate, Basilica of Saint Apollinare Nuovo, 6th century. |

The early believers scorned long-held Roman religious traditions. Many of their adherents came from the lower classes and seemed gullible. They refused military service, and met for clandestine rites rumored to include cannibalism, ritual murder, and incest. "You don't go to our shows," complained an early pagan critic, "you take no part in our processions, you are not present at our public banquets, you shrink in horror from our sacred games." All of which is to say, he concluded, the Christians "do not understand their civic duty."

Borg and Crossan suggest that Jesus's alternate reign and rule subverted major aspects of the way most societies in history have been organized. Whether ancient or modern, most societies have normalized a status quo of political oppression that marginalizes ordinary people, economic exploitation whereby the rich take advantage of the poor, and religious legitimation that says, "don't try to change things because God wants things this way." It's easy to think of other aspects of cultural conformity that Jesus would subvert, like ethnic stereotypes, media propaganda, gender roles, consumerism, and our degradation of planet earth.

Cucifixion icon, Sinai, 8th century. |

On Palm Sunday Jesus invites us to join his subversive counter-procession that leads to a sort of parallel universe. But he calls us not to just any subversion, subversion for its own sake, or to some new and improved political agenda. Christian subversion takes as its model Jesus himself. It aims for what Martin Luther King Jr. called "transformed nonconformity" (cf. Romans 12:1–2).

In one of the earliest Christian hymns, believers worshipped Jesus as one who "being in very nature God, did not consider equality with God something to be grasped, but made himself nothing, taking the very nature of a servant, being made in human likeness. And being found in appearance as a man, he humbled himself and became obedient to death—even death on a cross." Dying to self and the many demons of egoism, and living to serve others, will prove itself to be sufficiently and radically subversive. And so Paul instructs us in his epistle for this week: "have this attitude in yourselves which was also in Christ Jesus" (Philippians 2:5–11).

|

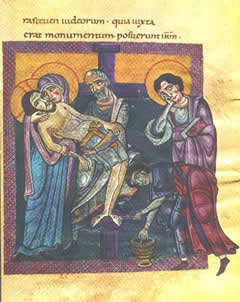

Descent from the Cross, 12th century, parchment, Nonantola (Modena, Italy), Abbey`s Library. |

Elsewhere Paul uses an economic metaphor when he writes that although Jesus was rich, yet for our sakes he became poor, that we through his poverty might become rich (2 Corinthians 8:9). As an old man Paul said that his own life had been "poured out like a drink offering" for others (2 Timothy 4:6). Identifying with Jesus and patterning our lives after him results in endless subversions — divestment of wealth rather than accumulation, renunciation rather than gratification, self-sacrifice rather than self-satisfaction, humility rather than exaltation, and peace for all rather than security for a few.

And so although Palm Sunday marked the beginning of the end for Jesus, his end showed the way for our own beginning.

For further reflection:

* Meditate on 2 Corinthians 5:19 and the ultimate meaning of Jesus's death: "God was in Christ, reconciling the cosmos to Himself."

* How might the "parallel universe" of Jesus subvert cultural conformity in your own life? What might it look and feel like? Can you point to one example either positive or negative?

* Consider:

March 19, 2008 marks the fifth anniversary of the US invasion of Iraq. The war has cost $500 billion so far —$275 million per day or $4,100 per household. Almost 4,000 U.S. soldiers have been killed and more than 60,000 wounded. 700,000 Iraqis have been killed and 4 million made refugees.

* Cf. Marcus Borg and John Dominic Crossan, The Last Week; A Day-by-Day Account of Jesus's Final Week in Jerusalem (2006).

Image credits: (1) Christopher Haas, Department of History, Villanova University; (2) http://vdjorbenadze.tripod.com/; (3) Museum of Antiquities, University of Saskatchewan; (4) Robert W. Brown, Dept. of History, University of North Carolina Pembroke; (5) Jugoslav Ocokoljić; and (6) Chiesa Cattolico di Torino.