|

The Decalogue: Ten Words on Life, Love, and Justice

A guest essay by David Gill (B.A., UC Berkeley; M.A., San Francisco State; Ph.D., University of Southern California). David is an organizational ethics consultant (www.EthixBiz.com for further info and a free subscription to his monthly zine) and also President of the International Jacques Ellul Society (www.ellul.org). He is the author of seven published books including Doing Right: Practicing Ethical Principles (IVP, 2004; an intro to Christian Ethics based on the Ten Commandments) and most recently It’s About Excellence: Building Ethically Healthy Organizations (Provo, UT: Executive Excellence Publishers, 2008). He serves as Professor of Business Ethics on the MBA faculty at St. Mary’s College (Moraga, CA) and sometime adjunct or visiting professor of Christian ethics for Fuller Seminary and Regent College.

For Sunday October 5, 2008

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year A)

Exodus 20:1–4, 7–9, 12–20 or Isaiah 5:1–7

Psalm 19 or Psalm 80:7–15

Philippians 3:4b–14

Matthew 21:33–46

|

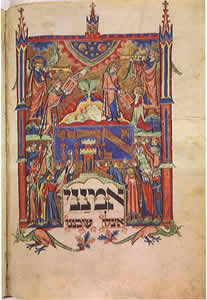

Moses receives the 10 commandments, Jewish prayer book, Germany, c. 1290. |

There was a time when I was clueless about the Decalogue (Greek: “deca” = “ten” + “logos” = “word”). To be precise, as a newly minted professor of Christian ethics at age 34, I was challenged by Professor Klaus Bockmuehl of Regent College (Vancouver BC) to take a careful look at the Ten Commandments as I constructed my courses.

Born and raised in a “dispensationalist” theological framework, then migrating to a hardcore Anabaptist theology and ethics, I viewed myself as a “New Testament” Christian and thought of “Law” as old school, and “Grace” as what’s happening now. But the more I immersed myself in what Scripture itself actually said (and let it challenge the assumptions of my theological tradition), the more I began to value and understand the Ten Words.

I like the formula of Karl Barth, that “the law is the form of the Gospel, and the Gospel of grace is the content of the law.” The form — the “letter”— of the law, by itself, is a hard, condemning message. But the content requires a form, a structure to mediate that content into our daily experience. The law is like a cup; the gospel is the coffee. If you have the cup without the coffee, the empty cup just reminds you of your thirst and what you are missing; but if you just have the coffee and no cup it is, practically speaking, impossible to get the coffee into your lived experience.

Most of us have heard that the great reformer Martin Luther opposed Law and Gospel. But what he opposed was “cups without coffee,” if I may extend my metaphor above. There was a lot of cup talk and not much coffee talk by the time he came along in the 16th century. But in his Larger Catechism, Luther says that “whoever knows the Ten Commandments perfectly knows the whole of Scripture.”

And remember that St. Paul himself says (Romans, Galatians) that despite how difficult its problems, we do not “set aside” the law. We embrace it, but with a renewed understanding.

Four Interpretive Angles

The Ten Commandments are, in themselves, the covenant between God and his people. They were kept and carried around in the Ark of the Covenant. They are the terms and conditions and guidelines of a covenant relationship. “I will be your God; you shall be my people” — and here is how we will treat each other.

First of all, the ten commandments (all ten) are the ten ways we express love to God. Both the Old Testament shema (Dt 6:5; recited twice daily by pious Jews) and Jesus (Mt 22:37; the great Love Commandment) teach that the Law is all about loving God with heart, soul, mind, and strength. All the commandments “hang” on this Love Command.

|

Moses, Salvador Dali, 1975. |

Second, both the “holiness code” (Lv 19:18) and Jesus (Mt 22:39) teach that the Law is also about loving one’s neighbor as oneself. And note carefully that it is not just the first half of the ten commandments that are the “love God” commands — and the second half the “love neighbor” commands. All ten commands are simultaneously ten ways to love God and ten ways to love your neighbor. Paul makes the same point in Romans 13:8–10.

Consider two examples. The first command, “You shall have no other gods before me,” is not just good for God, it is an act of love for my neighbor. Why? Because it is good for my neighbor for me not to make money or power my god; it is good for my neighbor for me to maintain the gracious, forgiving Yahweh as my God; it is good for my neighbor that my God is the Creator of all people, all nations, both sexes, and not some tribal deity. Second example: certainly it is loving to my neighbor that I not kill him or her; but the sixth command is just as certainly about loving God. I must not kill my neighbor, not just because my neighbor wouldn’t like it, but because God is the giver of my neighbor’s life. I cannot be loving God if I kill those who belong to him.

But there is an even deeper level to this twofold interpretation and application. One of the most basic of all biblical theological affirmations is that man and woman are created in the image and likeness of their Creator-Redeemer God. In some very profound ways, then, men and women are “like” their God. For example, like God, people have a will to create things, a desire for relationships, a value of beauty as well as usefulness, a capacity to communicate by word, and so on. If this is the case, when we learn the basic movements and components in loving God, we are also learning the basic movements in loving our neighbor-made-in-the-image-of-God. What God wants, we also want in some profound sense.

Third, the Ten Commands are ten principles of justice/righteousness. This is familiar territory: God’s law lays down his righteous, holy standards, “the right thing to do in his eyes.” So we can say that it is an act of love to make God the only one (the first commandment); but it is equally true to say that God has a right to sit on that divine throne in our life. It is simply unfair and unjust not to let God be God. So too it is loving to protect life (the sixth commandment), but it is equally true to say that God alone has the right to give and take human life and that people have a right to life as they stand before us in the world.

Fourth, the Ten Commands are ten principles of life and freedom. As the “prologue” in Exodus 20 so clearly indicates, the Decalogue is Ten Words from the God “who brought you out of Egypt, out of the land of slavery.” Contra dispensationalism, the Old Testament does not teach that “if you keep the commandments I will be your God and deliver you from bondage.” No, the redemption from Egypt and adoption as God’s people happens by grace and by God’s initiative before the law is given. The law’s primary function is to outline how to stay free and live out the life of love and justice in relationship with each other and with God. I think of the Ten Commands sometimes as ten warning signs to keep us away from potential slavemasters ready to ruin our freedom: e.g., nationalism (command #1: no other gods) . . . sexual addiction (commands #7 & #10: no to adultery, unbridled lust and sexual fantasy) . . . violence, retaliation (#6: murder) . . . workaholism (command #4: Sabbath), etc.

The Ten Principles

With this background in mind, then, here is what we find.

I: You shall have no other gods before me.

The first way we love God is to make him the only one. It is the principle of “exclusivity and the unique place.” He has a right to that place of worship and centrality in our lives. This choice is also good for our neighbors as indicated above. It sets us free from inferior and false gods. And it teaches us the basic principle that our spouses, kids, friends, and employees each need to have their own unique place of value in our lives (not God’s place but certainly their place of value that no one else can threaten or occupy).

II: You shall not make for yourself any idols or images of any kind.

The second way we love God is by letting him be free and alive, by not substituting some fixed image (artistic, theological, cultural) for his dynamic, living presence, speaking, listening, and acting in our daily lives. This is a living God. So too, people made in God’s image (our spouses, kids, colleagues) thrive when we let them be alive and growing; they shrink and suffer when we create images and stereotypes of them.

III: You shall not misuse the name of the Lord.

The first act of communication is to say the name of the other. Saying it often enough, and saying it with respect, is what sets the stage for the relationship. Do not use names in an empty, vain fashion. Learn the name, speak it with respect. The third way you love God or those made in his image.

IV: Remember the Sabbath day to keep it holy; Six days you shall labor and do all your work.

The fourth way we love God is to take time off, quality time every week, to be with him; yes (this is a double-command with two imperative phrases!), we love God by working for him (indeed, he has a right to our work for him; justice, not just love), but that is not enough. He wants to be loved by our stopping to take time with him. Same principle for loving anyone made in God’s image: work for them, take some time to be with them.

V: Honor your father and mother as the Lord your God has commanded you.

Fifth principle: honor (it means treat with respect and care) those who have been God’s agents to bring you life and truth. Luther saw this as broadly meaning respect for all authorities, political, ecclesiastical, familial, and otherwise. I see it more as “agent” than “authority.” Parents are (ideally) those who bring you life, care, teaching, encouragement. Anybody who plays those roles (however imperfectly) is to be honored. That shows love to the one who sent those agents into our lives.

VI: You shall not murder.

We love God by protecting the life and existence of his creatures. These lives belong to God, not us. For Luther and Calvin this meant feeding the hungry, sheltering the homeless, healing the sick, and calming disputes, not just refraining from shooting or knifing your enemy!

VII: You shall not commit adultery.

“What God has joined together let no one put asunder.” We love God by protecting the covenant relationships he has allowed or guided into existence (as crazy as they may sometimes appear to us!). Marriage is the main symbol of such relationships; adultery is wrong because it is a brutal attack upon and violation of a covenanted relationship established by God. More broadly, we protect and nurture the relationships of friends, parent and child, and so on.

VIII: You shall not steal.

And we protect the material infrastructure of people’s lives. In addition to our physical existence (#6) and our core relationships (#7), we all need food, clothing, shelter and other material things (#8). We are not disembodied spirits hovering around the planet. And “he owns the cattle on a thousand hills.” It is an act of love and justice toward God and toward his creatures that we protect people’s stuff, rather than try to take it from them.

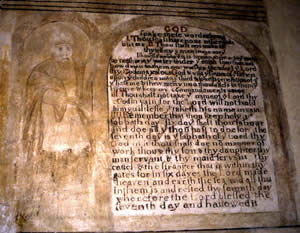

|

Moses and the 10 Commandments, 16th century church fresco. |

IX: You shall not bear false witness against your neighbor.

People need their reputation and they need truth in order to have any kind of chance at a life. We love God by avoiding falsehood and slander and gossip, and by being people who speak truth in love.

X: You shall not covet anything that belongs to your neighbor.

Finally, we live in a world in which our thoughts, intentions, attitudes, and spirituality are of fundamental importance. We love God by seeking a pure heart that thinks and wills the best for God and for our neighbors (and even our enemies). We avoid anger, greed, lust, covetousness, jealousy, envy, prejudice and the other deeply corrupting sins of mind and spirit. This is the tenth way we love God, and the tenth act of love for our fellow human beings.

Image credits: (1) Library of Congress; (2) PicassoMio; and (3) Medieval Wall Painting in the English Parish Church.website.