"The Glory and Honor of the Nations"

For Sunday May 9, 2010

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

Acts 16:9–15

Psalm 67

Revelation 21:10, 22 –22:5

John 14:23–29 or 5:1–9

Last week I watched the award-winning film called God Grew Tired Of Us (2005). It's based upon the book of the same title by John Bul Dau with Michael S. Sweeney, God Grew Tired of Us; A Memoir (2007). It's hard to imagine anyone surviving what Dau describes in the book and film. By the time he started copying books from a Kenyan refugee camp library, learned English and Swahili in order to understand school instruction, passed the Kenyan high school exam, then made it to Syracuse, New York, he had wandered a thousand miles over fourteen years from his bucolic village in southern Sudan.

|

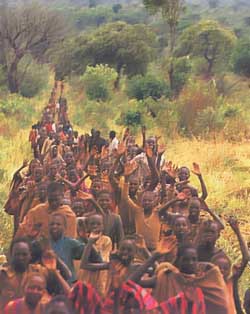

The "Lost Boys of Sudan". |

Sudan is the largest country in Africa, and one of the most complex (572 tribes that speak 114 languages). It's also one of the most war-torn. The Darfur genocide in western Sudan rightly grabs our attention, but for twenty-five years civil war raged in the southern part of Sudan. The "white" Arab and Muslim government in Khartoum has tried to impose strict Islam as the state religion for the entire country, but the black and Christian south rebelled. In 2005 a Comprehensive Peace Agreement was reached.

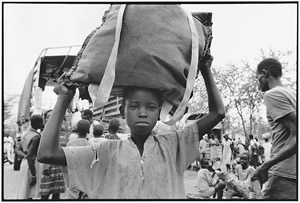

When the Khartoum government bombed Dau's village of Duk Payuel in 1987, he fled with thousands of other displaced Sudanese. He was thirteen years old. Rape, disease, pillage, daily burials, wild animals, famine (they sometimes ate mud and drank urine), government troops, and hostile tribes did not prevent Dau and some 265,000 Sudanese from reaching refugee camps in Ethiopia to the east. Most of them were young boys and a few men, as women and girls could hardly survive. They became known as the "Lost Boys of Sudan." When Ethiopian troops started slaughtering them, the refugees trekked 500 miles south to refugee camps in Kenya. By then Dau was eighteen. After nine years in the refugee camp, he was one of only 3,600 Sudanese refugees in Kenya who were resettled in the United States.

Dau is one of the very few success stories. He was totally self-sufficient about six months after he arrived in America. He finished community college, entered Syracuse University, met and married a Sudanese woman from his Dinka tribe, started several foundations to help Sudan, and sent most of his hourly wages back home. But at one point in the movie memory and emotion overwhelm Dau as he describes what he and tens of thousands of others endured: "I felt like God had forgotten us, that he grew tired of us."

|

Sudanese refugees. |

Psalm 67 for this week for reminds us that God is not a territorial or parochial god. He has not forgotten any nation or person. Rather, his salvation extends to "all nations." He "rules the peoples (plural) justly and guides the nations of the earth." His love and justice extend not just to one people or place, but to "all the ends of the earth." Originating from an ancient writer of a geo-politically marginal people, I'm always amazed at the cosmic scale of the Hebrew psalms.

The psalmist pushes us beyond all ethnocentric boundaries to embrace every "other," and beyond every egocentric preoccupation to worship only God. The reading from Revelation does likewise.

At first glance the "new heaven and new earth" seem narrowly Jewish — a perfected Jerusalem descends from heaven to earth, complete with twelve gates representing the twelve Hebrew tribes. Four thousand years ago, God formed Israel as a special people. Israel was and always will be a "singular" people, says Elie Wiesel, but they've never been a "superior" people. In electing one people God always intended to bless every nation. He promised Abraham that in him "all the families of the earth will be blessed" (Genesis 12:3).

In fact, the heavenly Jerusalem that descends to earth is a cosmopolitan city par excellence: "The nations will walk by its light, and the kings of the earth will bring their splendor into it. The glory and honor of the nations will be brought into it" (21:24–26). Flowing through the city center is a river, and on the banks of the river are "the tree of life. . . And the leaves of the tree are for the healing of the nations" (22:2).

The ancient promise to Abraham has become an empirical reality today. Luke's Acts of the Apostles begins in Jerusalem, proceeds geographically outward, and in his final chapter ends with Paul imprisoned in the imperial city of Rome. Under Roman house arrest, his last recorded prayer before martyrdom was for "all nations" (Romans 16:26). But that was only a modest beginning. Starting with a few uneducated, bedraggled disciples, today about a third of the world identifies itself as Christian, nearly twice as many as those who follow Islam or Hinduism (roughly one billion each).

Two radical corollaries follow from the global character of God's kingdom — the decentralization of your geography and the reorientation of your politics.

Christians are geographic, cultural, national and ethnic egalitarians. For Christians there is no geographic center of the world, but only a constellation of points equidistant from the heart of God. Proclaiming that God lavishly loves all the world, each person, and every place, the gospel does not privilege any country as exceptional. A Bosnian Muslim is no further away from God's love than an American Christian. A Honduran Pentecostal is no closer to God's love than an Oxford atheist.

Much has been written lately about American exceptionalism and our global dominance. In terms of economic, political, military, scientific and cultural influence, America is unrivaled. In that sense, it's accurate to say that America is "exceptional" (although there's no reason to think this will last forever, or that all our influence is good).

|

Lost boys. |

But from a theological or Christian point of view, America is no more or less "exceptional" in God's eyes than Sudan. While allowing for a natural and wholesome love, even pride, in your own country ("there's no place like home"), in the long run, Christian egalitarianism subverts every form of geo-political nationalism. Our ultimate citizenship, said Paul, is a spiritual one (Philippians 3:20).

Christian globalism also asks me to care as much about every country and people as I do my own. Christians grieve the deaths of 100,000 Iraqi civilians (some experts place the figure at more than 1.3 million; see justforeignpolicy.org) as much as the 4,385 American soldiers killed in Iraq, or the 1,025 soldiers killed in Afghanistan. Christians lament the human tragedy of cyclone Nargis that killed 140,000 people in Burma (2008) as much as they do the recent earthquakes in Haiti and Chile.

Christian globalism implies that your politics become reoriented, non-aligned, and unpredictable by normal canons. In the gospels Jesus never proposed any political program. There's no such thing as a "Christian" politics, and efforts by both Democrats and Republicans to co-opt Jesus for their side badly distort his message. Rather, Jesus calls us to something far more radical and demanding. He asks us to do what God Himself does, as expressed in two of the most famous verses in all the Bible. He calls us to "love the whole world" (John 3:16) and "your neighbor as yourself" (Mark 12:31).

For further reflection

* Consider: Although there has never been a time, place, culture, language, philosophy, science, or world view with which the Gospel has been entirely compatible, paradoxically, "there has also never been any picture of the world within which the confession of the faith has proved to be altogether impossible" (Jaroslav Pelikan).

* Contemplate: "The centers of the church's universality [are] no longer in Geneva, Rome, Paris, London, and New York," writes the Kenyan theologian John Mbiti, "but in Kinshasa, Buenos Aires, Addis Ababa, and Manila" [Quoted in Philip Jenkins, The Next Christendom; The Coming of Global Christianity (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002), p. 2.).

* Meditate: Is the core of my personal identity formed more by nationalistic cultural values or by the kingdom of God proclaimed by Jesus?

* Meditate: The apostle John envisioned heaven with people from "every nation, tribe, people, and language" (Revelation 7:9).

* For further reading: Philip Jenkins, The Next Christendom; The Coming of Global Christianity (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002); and The New Faces of Christianity; Believing the Bible in the Global South (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006); and Lamin Sanneh, Whose Religion is Christianity? The Gospel Beyond the West (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2003).

Image credits: (1) Pelogifam blog; (2) Mount Holyoke College; and (3) CoalitionOfWilling.org.