"Where is Your God?"

Reflections on a Lunch Time Phone Call

For Sunday June 20, 2010

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

1 Kings 19:1–4, (5–7), 8 –15a or Isaiah 65:1–9

Psalm 42 and 43, or Psalm 22:19–28

Galatians 3:23–29

Luke 8:26–39

At lunch yesterday a good friend called to say that he had been diagnosed with Non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Today he starts 18–24 weeks of chemotherapy. And so his story now merges with a narrative that's deeply embedded throughout the Bible and in human experience, whether in the earthquake rubble of modern Port-au-Prince or on a hillside in ancient Israel.

"Where is your God?" taunts the cynic in Psalm 42:3, 10.

"Lord, why have you forgotten and rejected me?" (Psalm 42:9, 43:3).

"I've had enough, Lord," mutters a dispirited Elijah (1 Kings 19:4).

|

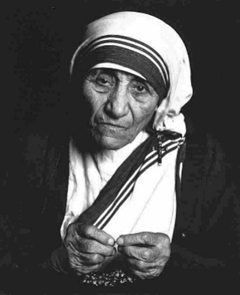

Mother Teresa. |

And in this week's gospel, a naked and homeless man tormented in body, mind, and spirit screams in desperation at the top of his lungs, "What do you want with me, Jesus!?" (Luke 8:28).

Hell and heartache will visit each one of us some time or another. No person is immune. Sometimes our suffering is personal and private, like my friend's cancer or Elijah's fear of Jezebel. At other times suffering assumes global proportions. Consider the 1.1 billion people in the world with no safe and reliable drinking water. Lacking the most basic of all human rights, a cup of water, these people live in an apocalyptic nightmare.

Such trials test the faith of even the most mature saints. That's one reason the psalms have been so beloved for three thousand years. They give voice to the most painful anguish of the human spirit. They strip away our pious platitudes and tired cliches, and in doing so invite us to do the same. With the psalmist I can "pour out my soul" to the Lord (42:4).

Back in 2007 some people suggested that Mother Teresa was a fraud or even a closet atheist. Those questions dogged her book of private correspondence called Come Be My Light. In numerous letters, which she repeatedly begged her superiors to destroy, Mother Teresa described her experiences of profound spiritual darkness that haunted her for fifty years. She admits that she didn't practice what she preached, and laments the stark contrast between her exterior demeanor and her interior desolation: "The smile is a big cloak which covers a multitude of pains. . . . my cheerfulness is a cloak by which I cover the emptiness and misery. . . . I deceive people with this weapon."

Mother Teresa describes the absence of God's presence in many ways — as an emptiness, loneliness, pain, spiritual dryness, or lack of consolation. "There is so much contradiction in my soul, no faith, no love, no zeal. . . . I find no words to express the depths of the darkness. . . . My heart is so empty. . . . so full of darkness. . . . I don't pray any longer. The work holds no joy, no attraction, no zeal. . . . I have no faith, I don't believe." She rebukes herself as a "shameless hypocrite" for teaching her sisters one thing while experiencing something far different.

David Van Bima of Time magazine called this disparity between her private and public worlds "a startling portrait in self-contradiction" (August 23, 2007). I think Van Bima is wrong. I credit Mother Teresa with the brutal honesty that we see in the Scriptures this week. Other saints have described similar experiences of near despair. The Spanish mystic John of the Cross (1542–1591) made famous a phrase that has passed into our every day lexicon — the "dark night of the soul." And the 19th-century French Carmelite nun Thérèse of Lisieux (1873–1897) once told her fellow nuns,"If you only knew what darkness I am plunged into." She compared her spiritual desolations to a dark tunnel.

|

John of the Cross and Teresa of Avila. |

The Scriptures this week and the wisdom of the saints encourage us to embrace rather than to deny our feelings of spiritual anxiety. Some degree of anxiety is normal and even healthy; it can be a sane response to an insane world. The apostle Paul writes how he was "harassed at every turn — conflicts on the outside, fears within" (2 Corinthians 7:5).

One of the reasons I've loved reading the desert mothers and fathers of the fourth century is for their disarming candor, brutal realism, unqualified empathy, and tender compassion. These saints describe how in the trackless solitude of the Egyptian desert they discovered a cacophony of voices in the geography of the human heart. I've always loved the blunt advice of St. Makarios of Egypt (5th century): "I am convinced that not even the apostles, although filled with the Holy Spirit, were therefore completely free from anxiety… Contrary to the stupid view expressed by some, the advent of grace does not mean the immediate deliverance from anxiety."

Saint John of the Cross wrote that "silence is God's first language." In an oft-quoted riff on this, Thomas Keating suggests that "everything else is a poor translation. In order to hear that language, we must learn to be still and rest in God." Even amidst exterior chaos we can aim for interior solitude and a sense of God's nearness. That's what we see in the story of Elijah.

When Jezebel threatened to murder Elijah, he rightly feared for his life. He knew better than to trifle with people in political power. After retreating into the desert where he hoped to die, angels rescued him and sent him back to Horeb, to "the mountain of God." There he entered a cave where "the word of the Lord" spoke to him. Elijah whined to God in something like a pity party, complaining that he alone was faithful and that Jezebel threatened to kill him.

And then God spoke, but not like Elijah expected. Standing on Mount Horeb, a "great and powerful wind" blasted the mountain and shattered the rocks, "but the Lord was not in the wind." An earthquake then shook the earth, "but the Lord was not in the earthquake." Fire then scorched the land, "but the Lord was not in the fire." After these dramatic acts of nature we read that "after the fire came a gentle whisper."

Thérèse of Lisieux. |

It was in that faint but discernible whisper that God spoke to Elijah, and that perhaps He speaks to us today in our own extremities. Our job is to make a space and a place where we can hear those divine and gentle whispers.

Many saints have advised that we meet God not at the end of our troubles but in the midst of them. The poem "After Augustine" by Mary Elizabeth Coleridge (1861–1907) makes this point:

Sunshine let it be or frost,

Storm or calm, as Thou shalt choose;

Though Thine every gift were lost,

Thee Thyself we could not lose.

At our best, what we seek is not mere deliverance from pain and misfortune; what we seek is the presence of God Himself.

For further reflection

* How have tests and trials shaped your faith?

*

See the book by DA Carson, How Long, O Lord? Reflections on Suffering and Evil.

* Psalm 42:5, "Why are you downcast, O my soul? / Why so disturbed within me? / Put your hope in God, / for I will yet praise him, / my Savior and my God."

Image credits: (1) Wheat for Paradise blog; (2) PhotoBucket.com; and (3) Wikipedia.org.