"Don't Worry About Your Life":

Jesus Speaks to Our Fears and Anxieties

For Sunday August 8, 2010

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

Isaiah 1:1, 10–20 or Genesis 15:1–6

Psalm 50:1–8, 22–23 or Psalm 33:12–22

Hebrews 11:1–3, 8–16

Luke 12:32–40

Every Thursday when The New Yorker hits my mail box, I immediately sit down and thumb through all the cartoons. I like them so much that my daughter gave me a desktop cartoon-a-day calendar, so every morning I enjoy a new bite of irony. I cut out the cartoons and give them to friends if I think they'll connect with some specific life experience — a bad business deal, a trip to the doctor, a dig at gender relationships, or some wry observation about marriage.

One recent cartoon earned my "best ever" accolade. I handed it to my wife and said, "this explains me." The sketch pictures a man sitting in his living room with a look of panic on his face. He's dropped his book and his hair stands on end. He's yanked his legs off the floor and onto the chair where he clutches them in his arms. There's a bomb on the floor that someone tossed through his window. Shattered glass litters the floor as the fuse burns down. In the punch line he confesses to his wife: "It's my fault — I wasn't worrying enough."

|

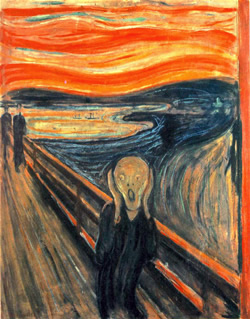

The Scream, Edvard Munch, 1893. |

Another cartoon taped onto our kitchen cabinet pictures a man in bed late at night. He's sitting up, scribbling on a note pad, and talking on the phone. In the caption he tells his friend, "When I can't sleep, I find that it sometimes helps to get up and jot down my anxieties." Every square centimeter of the bedroom walls is covered with dozens of scribbled worries — war, recession, killer bees, aging, calories, sex, balding, radon gas, and so on.

As a natural born worrier, I love these characters with their exaggerated sense of responsibility. I make lists, then mark things off after I do them. I'd rather be an hour early than five minutes late. Brooding and internal soliloquies come naturally to me. My exterior demeanor is calm, but my internal engines are always racing, and at night when it's time to sleep I can't find the "off" switch. Truly relaxing is a challenge. Overcompensation? That's my specialty. Obsessing about a trivial detail? I've perfected the art. As the cartoon puts it, just think of all the bad stuff that will happen if I don't worry enough.

I try not to be too hard on myself. My pop psychological analysis suggests that I inherited a "worry gene" from my mother. I'm not clinically depressed like she was for the last twenty years of her life, and I don't chew my fingernails like I remember my father doing when I was in high school. But the worrier in me wonders — anything's possible, and there's still plenty of time.

|

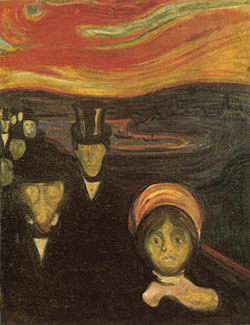

Anxiety, Edvard Munch, 1894. |

Not all worries are merely imagined or artificial; some are genuinely real. There are legitimate reasons to worry. Among my friends and family are divorce, unemployment, eating disorders, bad mortgages, chemotherapy treatments, sleep disorders and struggling kids (who have great parents). And when you look at the larger world there are environmental disasters on an unprecedented scale, the collapse of the housing and financial markets, rogue states, and the threat of nuclear terrorism.

In the same issue of the New Yorker as the first cartoon above (June 14 and 21, 2010), an article called "Fresh Hell" explores the boom in "dystopian fiction" among young readers. Perhaps it has something to do with the world they experience every day? "The typical arc of the dystopian narrative," writes the author, "mirrors the course of adolescent disaffection." These dystopian tales, he says, are about "the world being broken or intolerable." Although we manufacture some worries by projecting our anxiety onto the world, other worries are sane responses to an insane world.

The gospel for this week anticipates our personal neuroses and our legitimate anxieties, but not in the way that we might want or expect. Jesus, observes Diarmaid MacCulloch in his new book Christianity (2010), plays by a different set of rules. In the gospels, observes MacCulloch, "Jesus is his own authority." The coming kingdom that Jesus announced "produced outrageous inversions of normality," like paying a laborer who worked only one hour an entire day's wages. Jesus subverts our cultural conventions and natural intuitions with a sense of relish. And such is his advice to us about anxiety.

"Don't worry about your life," says Jesus.

"Don't be afraid."

|

Separation, Edvard Munch, 1900. |

Instead of hoarding money, give it away. Instead of worrying about yourself, care for others. Beyond all your prudent planning for the cares of life, abandon yourself to a fatherly God who is all-powerful and intimately personal. After you've hedged every bet and calculated every contingency, enjoy the beauty of the morning birdsong and the glory of a field of flowers. Having fretted over a life of worries, whether artificial or genuine, consider an act of faith. Live like what you believe is actually true. After you've run yourself ragged like a godless "pagan" (12:30), says Jesus, rest in the knowledge of a benevolent Being.

How so?

"Your Father knows what you need" (Luke 12:22, 30, 32).

I'm not sure how to live free from worry, anxiety and fear, but I did recently appreciate the wisdom of ninety-one-year-old Huston Smith in his new book Tales of Wonder, Adventures Chasing the Divine: An Autobiography (2009). Born to Methodist missionary parents in rural China in 1920, Smith enjoyed a distinguished career as a scholar of world religions at Washington University, MIT, Syracuse, and Berkeley. His book The World's Religions, first published in 1958, has sold 2.5 million copies as an introductory university textbook on the subject.

|

Ashes, Edvard Munch, 1894. |

Smith has been been married to his beloved Kendra for almost seventy years now. They lost an adult child to cancer and a grand daughter to a mysterious murder. He recounts his encounters with Huxley, the Dali Lama, and his decades of globetrotting. In the second half of the book he describes his personal Christian faith, and how he "never saw a religion I didn't like." Now near the end of his long life, Smith says that he's absolutely convinced of at least one thing: "We are in good hands."

For further reflection:

* Consider Philippians 4:7: "Do not be anxious about anything, but in everything, by prayer and petition, with thanksgiving, present your requests to God."

* Meditate on 1 Peter 5:7: "Cast all your anxiety on him because he cares for you."

*

Cf. St. Makarios of Egypt (5th century): "I am convinced that not even the apostles, although filled with the Holy Spirit, were therefore completely free from anxiety… Contrary to the stupid view expressed by some, the advent of grace does not mean the immediate deliverance from anxiety."

Image credits: (1) ibiblio.org; (2) MW Capacity; (3) in illo tempore; and (4) Wikimedia.org.