Believing Isn't Seeing:

"None of Them Received What Had Been Promised"

For Sunday August 15, 2010

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

Isaiah 5:1–7 or Jeremiah 23:23–29

Psalm 80:1–2, 8–19 or Psalm 82

Hebrews 11:29–12:2

Luke 12:49–56

When I was in college I had a friend who said that she loved reading the Bible — that is, until she studied the book of Hebrews. That epistle stymied her. If you've read Hebrews, then maybe you can empathize. It's difficult to understand, to say the least, and its many complex issues have kept capable scholars scratching their heads for two millennia.

Part of the problem is that Hebrews, like every piece of historical literature, was written in a particular time and place, by a certain author, for a specific reason, and to a unique audience. Both the authorship and the recipients of Hebrews are lost to us today. There are many conjectures about who wrote Hebrews, but perhaps Origen (185–250) said it best: "Only God knows." Identifying the audience and the date when the book was written are a little different; it's an exercise in analyzing tantalizing tidbits of information internal to the text, and then making educated guesses.

|

Paradise with Christ in the lap of Abraham, 13th century Germany. |

The recipients of the letter are second-generation believers who heard the gospel from first-generation Christians (2:3). The text's elegant Greek, its quotations from the Greek translation of the Hebrew Old Testament (LXX), and its distinctly Jewish themes all suggest that the readers were a community of Hellenistic Jewish believers.

Its date is early enough that the author refers to the priesthood and temple sacrificial practices in the present tense, which could mean the letter was written before the temple's destruction in 70 AD. It's hard to imagine a date after 70 AD since this thoroughly Hebraic book never mentions that catastrophic destruction of the center of Judaism. It's also early enough that the recipients believed in the imminent return of Jesus (1:2, 10:25, 37), a belief that turned out to be wrong and therefore gradually waned as the decades receded.

On the other hand, its dating is late enough for the readers to have experienced severe trials and tribulations, a situation that was not the case until several decades after Jesus. The author describes how the believers experienced the confiscation of their property, imprisonment, public insults, persecutions, the discontinuation of their meetings (presumably out of fear of the authorities), and a "great contest in the face of suffering" (10:32–34). Paul's young protege Timothy is still alive after his release from prison (13:23).

|

God covenants to make Abraham a father of many nations, Marc Chagall, 1931. |

Finally, we also know that when a fire broke out in Rome on June 18, AD 64 and destroyed about half the city, the psychopathic emperor Nero, whom some thought had started the fire himself, deflected criticism by blaming the Christians. In his Annals the Roman historian Tacitus (55–117) describes how Nero punished the Christians with "refined cruelty." Before killing the Christians, says Tacitus, Nero "amused the people" with sadistic tortures: "Mockery of every sort was added to their deaths. Some were dressed in furs, to be killed by dogs. Others were crucified. Still others were set on fire early in the night, so that they might illumine it. Nero opened his own garden for these shows, and in the circus he himself became a spectacle, for he mingled with the people dressed as a charioteer."

Connecting these dots leads me to conjecture that Hebrews was written during a narrow window of time, after the fire in Rome in 64 AD and before the destruction of the temple in 70 AD. The context was that Jewish believers faced the challenge of significant persecutions.

A Christian living under Nero might have easily believed that a reign of terror and not the reign of God was imminent. Imprisonment and government confiscation of property would have corroded community morale. No wonder some people stopped meeting together. These beleaguered believers, says the writer, were tempted to "shrink back," to deny the faith, and to "throw away" their confidence (10:35, 38, 39). The author thus encourages his readers to "draw near," and to persevere in "full assurance of faith" and "unswerving hope" (10:22, 23). In particular, he exhorts them to imitate the faith of the saints who had gone before them.

|

The call of Abraham, ceramic relief by Richard McBee, 1980. |

A Christian who lost house and home, endured public ridicule, or saw a loved one mauled to death in the colossal Circus Maximus (which held 250,000 people) might ask many honest, hard questions about God's promises. Does God keep his promises? Exactly what does he promise? And what does it mean to believe God's promises? God's promises loom large in Hebrews 10 and 11. In fact, the word "promise" and its derivatives occur at least ten times in those two chapters.1

The author's line of thought is book-ended by two remarkably candid admissions. I've typically read Hebrews 11 as a sort of hall of fame of spiritual super stars. True, it honors saints who "conquered kingdoms, shut the mouths of lions, and quenched the fury of flames" (11:33–34). But this week when I read more carefully I discovered a different sort of saint. Alongside these mighty saints who "gained what was promised" (11:33), there were many saints who "did not receive what had been promised" (11:13, 39).

Here's how Hebrews describes the latter saints: "Others were tortured.… some faced jeers and flogging, while still others were chained and put in prison. They were stoned; they were sawed in two; they were put to death by the sword. They went about in sheepskins and goatskins, destitute, persecuted and mistreated — the world was not worthy of them. They wandered in deserts and mountains, and in caves and in holes in the ground. These were all commended for their faith, yet none of them received what had been promised" (11:35–39). This description is not a rhetorical exaggeration; it could easily describe the life of a Christian under ancient emperors like Nero or Diocletian, or modern despots like Hitler, Stalin, Mao, or Saddam Hussein.

These exemplars of faith remained sure of what they hoped for but did not see, certain of what God had promised but they did not experience: "This is what the ancients were commended for" (11:2). Abraham is only one, but perhaps the most important example, of how for "the ancients" believing was far different than seeing.

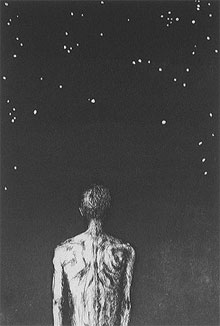

|

Your descendants will be as numerous as the stars, Genesis 22:17. |

Abraham journeyed from a present clarity into a future of profound ignorance. He journeyed from what he had to what he did not have, from the known to the unknown, from everything that was familiar to all things strange. Thus Hebrews commends his radical obedience to God, which defied both the inner propensities of human nature and the outer pressures of cultural conformity: "By faith Abraham, when called to go to a place he would later receive as his inheritance, obeyed and went, even though he did not know where he was going. By faith he made his home in the promised land like a stranger in a foreign country" (11:8–9).

When his end came, Abraham died "without having received the promise" (Hebrews 11:13). In the words of Edwin Muir's poem Abraham, "The Promise had not come, and he left his bones, / Far from his father's house, in alien Canaan." With the stuff of his human life unfinished and the promises of God unfulfilled, Abraham became "the father of us all" (Romans 4:16).

[1] Footnote: on "promise" see Hebrews 10:23, 36; 11:9 (2x), 11, 13, 17, 18, 33, 39

For further reflection:

* Reflect on the truth that God "gives life to the dead and calls things that are not as though they were" (Romans 4:17, 21).

* Meditate: "By faith Abraham, when called to go to a place he would later receive as his inheritance, obeyed and went, even though he did not know where he was going. By faith he made his home in the promised land like a stranger in a foreign country" (Hebrews 11:8–9).

* Where are you on your spiritual journey?

Image credits: (1) National Gallery of Art; (2) Time.com: Genesis Reconsidered; (3) Richard McBee; and (4) Galerie Jean-Marc Laik.