Beyond a Sentimental Gospel:

The Slaughter of the Innocents

For Sunday December 26, 2010

First Sunday After Christmas

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year A)

Isaiah 63:7–9

Psalm 148

Hebrews 2:10–18

Matthew 2:13–23

Stanley Hauerwas of Duke University once observed that sentimentality is one of the greatest enemies of understanding the gospel. Perhaps there's no time when we're more susceptible to this danger than at Christmas with the stories about the birth of Jesus. What parent hasn't gushed with pride watching his child play a shepherd in a bathrobe or an angel with a coat hanger halo? It's difficult to read words like "they wrapped him in swaddling clothes" and not melt into a puddle of sentimentality.

|

The Holy Innocents by Giotto di Bondone. |

A very gruesome gospel this week disabuses us of all such Hallmark readings of the Bible. Matthew yanks us back into the violent political realities "during the time of king Herod" (2:1). The story of the pagan magi worshipping Jesus ends abruptly when king Herod slaughters innocent children in order to strengthen his rule. This old story is re-enacted many times and in many ways in our own day when political powers annihilate their opposition to protect their power; it's certainly not a story that you'd teach with a flannel graph in a children's Sunday school.

With Christmas carols still echoing in our ears, the church liturgical year pivots sharply from joy and celebration to a most unlikely feast day — "the slaughter of the innocents." The church honors the toddlers of Bethlehem as the first martyrs of the gospel. By the late fifth century the "slaughter of the innocents" was the subject not only of church liturgy, art, and literature, but also mentioned in culture at large.

Whereas the pagan magi of Persia worshipped the baby Jesus, Herod of Rome tried to kill him. He had, after all, murdered his own sons (cf. Josephus). We don't normally associate the birth of a baby with the demise of political power, but Matthew does. His political parody is transparent. And at least we can give credit where it's due; Herod sensed a threat to his power and took brutal action against it.

Matthew contrasts two rival kings who rule not only over one people (the Jews) but over all the world. One king must give way. The subplot of king Herod almost overshadows the main plot of the adoration of the magi.

The magi came to worship Jesus (2:2), and that's what they did. Upon seeing Jesus and Mary, “they bowed down and worshipped Him,” offering him gifts of gold, incense and myrrh. Herod tells his confidants that he too wants to worship Jesus (2:8), but that's a lie, and a reminder for us today when political leaders flaunt their faith. Matthew says that when king Herod heard the news of another king he responded in fear, paranoia, and eventually infanticide.

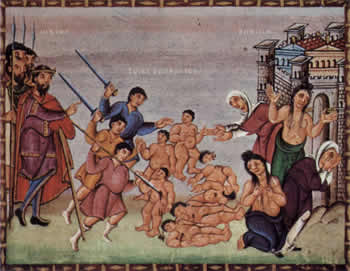

|

10th century illuminated manuscript. |

Herod "the Great" (c. 73–4 BC), as he was known, had been given the title “King of the Jews” in 40 BC, and after consolidating his power he ruled over Judea for 33 years (Luke 1:5). Infamous for his brutality, the last thing he wanted was a rival over his Judean domain. So suspicious and insecure was he that he called a secret meeting of religious leaders and extracted information about the exact time and place of the birth of the new king, Jesus, knowledge that would later prove lethal.

After worshiping Jesus, the magi set out to return to their country. But God warned them in a dream not to return to Herod, who had demanded that they come back with precise information. They disobeyed Herod (another lesson for us?) and returned home “by another route.” When he learned that the magi had tricked him, Herod erupted in a furious rage and murdered all the male children two years old and younger who lived in Bethlehem and its vicinity.

Meanwhile, Mary, Joseph and the baby Jesus fled to pagan Egypt where they found asylum. The political ironies in the flight to Egypt are remarkable. The infant Son of God fled as a displaced refugee to a foreign country, Egypt, Israel's sworn and symbolic enemy that had oppressed the Hebrews for 430 years (Exodus 12:40). The place where Pharaoh had unleashed his own infanticide against the firstborn Israelite children (Exodus 1:6–22) became a refuge for Jesus.

In the end, and just as with the Egyptian Pharaoh, it was king Herod the Great who died, about 4 BC. And just as in that ancient story it was the baby Moses who survived, so too did the baby Jesus. King Jesus returned to settle in the town of Nazareth in the district of Galilee, although he was careful to avoid Herod's son Archelaus who took his place.

There are, in fact, five Herods in the New Testament, and to a person they all persecuted Jesus and the early church. In addition to Herod the Great, there is his older son Archelaus born of his wife Malthace (Matthew 2:22), who reigned only a few years and was deposed in 6 AD. Then there's Herod's younger son by Malthace, Herod the tetrarch (Luke 3:19), who is famous for murdering John the Baptist on a dinner party dare because John denounced his affair with his brother's wife (Mark 6:14–29), and for his encounter with Jesus at his trial (Luke 23:7). Fourth, there's Herod King Agrippa (Acts 12:1), the grandson of Herod the Great, who murdered James and tried to murder Peter (Acts 12:1ff). Finally, there's King Agrippa's son, also named Agrippa, who bantered with Paul amidst great pomp and exclaimed that Paul was trying to convert him (Acts 25:13–26:32).

|

The Massacre of the Innocents at Bethlehem by Matteo di Giovanni. |

All these Herods do the opposite of the magi; they work hard to make the subversive kingdom of Jesus subservient to the political power of the state. But these Herods, whether ancient or modern, are right about one thing; if Jesus is Lord, then caesar is decidedly not lord.

In her own reflections on this text, Lutheran pastor Pam Fickenscher observes: "You could make a good argument that we should save this story for another day — Lent, maybe, or some late night adults-only occasion. But our songs of peace and public displays of charity have not erased the headlines of child poverty, gun violence, and even genocide. This is a brutal world. Today the victims are statistically less likely to be Jewish and more likely to be from Darfur, or Zimbabwe, or Iraq, but the sounds of Rachel weeping for her children are not uncommon. If we could hear them, they would drown out our cheerful, tinny carols every 20 seconds or so."

The birth of the baby Jesus, then, is the antidote to all sentimentality and every form of cheap comfort. Rather, the events surrounding his birth remind us how the savior of the world "shared in our humanity" and was "made like us in every respect." Because he himself suffered our every pain and sorrow, beginning from an infanticide at his birth and lasting to his death as a criminal, "he is able to help those who suffer" (Hebrews 2:10–18).

Image credits: (1–3) Wikipedia.org.