Ours the Cross, the Grave, the Skies

A guest essay by Rebecca Lyman. Rebecca is the Garrett Professor of Church History emerita from The Church Divinity School of the Pacific, Berkeley, and an Episcopal priest. She has written various books and articles on ancient Christianity, and lives with her husband and children in Woodside, CA. Raised in the Midwest, she has a particular interest in landscape and spirituality.

For Sunday April 24, 2011

Easter Sunday

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year A)

Acts 10:34–43 or Jeremiah 31:1–6

Psalm 118:1–2, 14–24

Colossians 3:1–4 or Acts 10:34–43

John 20:1–18 or Matthew 28:1–10

When we light the fire at the Easter Vigil or greet the morning dawn at the sunrise Easter service, I like to think that darkness and death are not only overcome, but redeemed with us into the arms of God: the beauty of darkness is deepened by the Light of Christ and death is now only part of our physical journey home. God has become all in all.

|

Fresco in Chora Church, Istanbul, c.1315, Christ raises Adam and Eve. |

I learned this from Ansel Adams as well as from St. Paul. In his black and white photographs, Adams portrayed the whole range of tones from deepest black to pure white. Black and white are not oppositions as much as ends of a continuous range of light. His development technique overcame the limitations of the photographic paper to reproduce more closely the ratio of the human eye: we see much more than what a camera could reproduce. In his photographs of Yosemite snow and granite, Adams revealed to us what we physically see. Our minds and eyes are no longer disconnected. In Adams' photographs we see light spread throughout the zones of black and into white again.

On Easter the resurrection stories of Jesus connect our eyes and hearts to our minds as Gethsemane becomes Eden. We have spent a week soaked in pain, separation, betrayal, and fatal suffering. What our hearts sought, our eyes did not find in the awful torture and death of Christ. None of this was what should have happened to a good man in Jerusalem. The male disciples flee and the women disciples stay, but all see nothing but the relentless victory of death.

Now in the early morning, the women encounter grief and joy as the darkness of the tomb gives way to light as dazzling as snow and lightning. The places that we knew were empty of hope are filled with divine presence, and the world as a whole has been remade new. We go to the garden looking only to be near our lost beloved, and find ourselves embraced by Love itself.

This is the night, we pray in the Easter Vigil, when Israel came out of Egypt, when all who believe in Christ are delivered, when Christ broke open the bonds of death. This is the most holy and blessed darkness where restoration and healing come from “Christ, the Morning Star who knows no setting—he who gives his light to all creation.”[1]

These places in ourselves that we avoid are exactly where God makes a home. What we consider to be tombs of our buried hope and dreams become the gardens of God’s renewal. The sharp realities of suffering, death, and grief are essential to the continuum of love and joy at Easter; their very darkness is what causes the light of resurrection to dazzle.

|

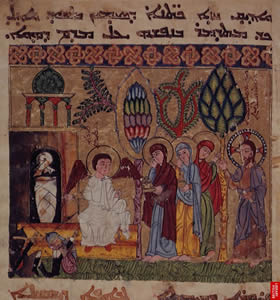

Holy Women at the Tomb: Syriac Gospel Lectionary, Northern Iraq, 1216–20. |

A powerful Orthodox icon shows Jesus pulling Adam and Eve out of their tombs as reality is reversed, and death no longer can keep us captive, instilling despair and nihilism. Death has no dominion after resurrection.

Philip Pullman in his books is eloquent about the relief one feels in no longer straining to believe in the fables of Christianity; one can be honest at last. Yet, Rowan Williams pointed out that Christianity is simple, but never simplistic: “You only get anywhere near the truth when all the easy things to say about God are dismantled, so that the image of God is no longer just a big projection of your self-centered wish fulfillment fantasies. What is left? Either you sense you are confronting an energy so immense and unconditioned that there is no adequate words for it or you give up.”[2]

I like to think of creation and resurrection as this immense energy that moves and illuminates our ordinary life rather than verbal propositions to be affirmed or denied. Doctrines do not satisfy us; life in God does. Walt Whitman could have written this poem about seeing and believing on Easter morning:

Of the terrible doubt of appearances,

Of the uncertainty after all, that we may be deluded,

That may-be reliance and hope are but speculations after all,

That may-be identity beyond the grave is a beautiful fable

only,

May-be the things I perceive, the animals, plants, men, hills,

shining and flowing waters,

The skies of day and night, colors, densities, forms, may-be

these are (as doubtless they are) only apparitions and

the real something has yet to be known,…

To me these and the like of these are curiously answer’d by

my lovers, my dear friends

When he whom I love travels with me or sits a long while

holding me by the hand,

When the subtle air, the impalpable, the sense that words

and reason hold not, surround and pervade us,

Then I am charged with untold and untellable wisdom, I am

silent, I require nothing further.

I cannot answer the question of appearances or that of

identity beyond the grave.

But I walk or sit indifferent, I am satisfied.

He ahold of my hand has completely satisfied me.

Mary Magdalene goes to the garden seeking her teacher, and finds not a new revelation, but the One she loves. The stories of the resurrection appearances are not philosophical arguments, but rather affirmations of unbroken relationships within divine reality. Only something so ordinary as the sight and sound of your lost friend could be this holy. We have come looking for nothing else. Love in its incredible tenacity and mysterious appearances walks with us in our grief and skepticism. Only in its light from birth to death do we begin to understand the ranges of existence seen and unseen.

|

Holy Women at the empty tomb, mosaic in Sant'Apollinare Nuovo, Ravenna, c.500-20 AD. |

This is almost what my father said to me in his last months of dying this year from prostate cancer: “I may be gone, but the love continues.” This year brings me a strange Easter in being an orphan for the first time. I am still a preacher’s kid, and I will miss my dad’s Methodist enthusiasm which soaked my childhood Easters in Wesley's hymns, new dresses and hats, the smell of lilies, and finding the first crocus under the Midwestern snow. My grieving and his painful absence feels to me like Henry Vaughn’s “deep, but dazzling darkness,” bewildering and yet utterly bound up in the mystery of Love which does not let us go.

To celebrate Easter is to know that the cross can be the tree of life and utter despair can yield to joy. This is the deep renewal that we receive from each other and from our world each day. We are free to live, free to act in ways that bring God’s justice and forgiveness to all those caught in suffering and despair. Through Jesus the darkness is now full of grace and failing mortals are loved into eternity. In seeing our death, we see now life everlasting, in darkness we see the presence of light, in our bloody and blessed world we see everywhere the face of our Beloved: “Made like him, like him we rise/Ours the cross, the grave, the skies.”[3]

Notes:

1 The Book of Common Prayer (Episcopal Church), p. 287.

2. Review of The Good Man Jesus and the Scoundrel Christ by Philip Pullman in The Guardian, April 3, 2010.

3. Charles Wesley, “Christ the Lord is Risen Today!”

Image credits: (1) Wikimedia.org; (2) The British Library, Online Gallery; and (3) Sacred-Destinations.com.