The Judgment of Injustice:

The Feast of Christ The King

For Sunday November 20, 2011

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year A)

Ezekiel 34:11–16, 20–24

Psalm 100 or Psalm 95:1–7

Ephesians 1:15–23

Matthew 25:31–46

For my birthday my daughter gave me a tiny lepton or widow's mite that was issued by Alexander Jannaeus, the king of Judea from 103 to 76 BC. The coin reminded me how, on this last Sunday of the liturgical year, Christians celebrate a king and a kingdom, albeit one that subverts the ways of this world.

Few people live under a king today, so the metaphor of kingship feels understandably irrelevant. We're also repulsed at how the reigns of kings meant a reign of terror for most subjects — massive wealth and power attained by cruelty, domination and exploitation, which was then passed on by birthright to those who did nothing to earn or deserve it. Then there are the Christian leaders throughout church history who have mimicked the worst characteristics of kings.

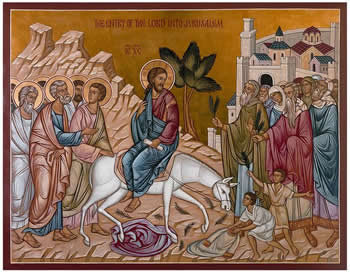

|

King Jesus enters Jerusalem. |

Nonetheless, the feast of Christ the King reminds us how deeply the language of kingship is embedded in the Christian story. The earliest followers of Jesus, and especially his detractors, used the language of kingship to describe who he was, what he said, and what he did. If you excised the language of kingship from the gospels, its meaning and message would be impoverished.

Pagan magi inquired at the birth of Jesus, "where is he who has been born king of the Jews?" These pagan star gazers worshipped Jesus with their gifts. Mary prophesied how her baby would "bring down rulers from their thrones," indicating that this king would reverse economic and political power structures.

Jesus's very first words spoken in public proclaimed that "the kingdom of God is at hand."

The language of kingship also characterizes Jesus's death. His "triumphal entry" into the clogged streets of Jerusalem on Palm Sunday was a deeply ironic, highly symbolic, and deliberately provocative act. It was street theater that dramatized his mission and message. He didn't ride a donkey because he was too tired to walk or because he wanted a good view of the crowds. The Oxford scholar George Caird characterized Jesus's triumphal entry as more like a "planned political demonstration" than the religious celebration that we sentimentalize today.

Borg and Crossan imagine not one but two kings entering Jerusalem that Friday morning in the spring of AD 30. In a bold parody of imperial politics, king Jesus descended the Mount of Olives into Jerusalem from the east in fulfillment of Zechariah's ancient prophecy: "Look, your king is coming to you, gentle and riding on a donkey, on a colt, the foal of a donkey."

Jesus was later dragged to the Roman governor's palace for three reasons, all political: "We found this fellow subverting the nation, opposing payment of taxes to Caesar, and saying that He Himself is Christ, a King." They got one thing right: if Jesus was king, then Caesar, Pharaoh, Herod and Pilate were not king.

Pilate met the angry mob outside the praetorium, then grilled Jesus alone back inside. "Are you the king of the Jews?"

|

The king crowned with thorns. |

"My kingdom is not of this world," Jesus replied. "My kingdom is from another place."

"You are a king, then!" mocked Pilate.

"Yes, you are right in saying that I am a king."

Pilate went back outside, declared that Jesus was innocent, then had his soldiers beat, flog, and humiliate him with purple robes and a crown of thorns befitting a man whom he miscalculated was a political failure: "Hail, O king of the Jews!" they mocked.

Back outside, the mob hounded Pilate: "If you let this man go, you are no friend of Caesar. Anyone who claims to be a king opposes Caesar." Pilate thus found himself sandwiched between angering the mob and betraying his emperor.

He caved in: "Here is your king. Shall I crucify your king?"

"We have no king but Caesar!" This tragic reduction of human identity to politics characterizes our own age.

When Pilate crucified Jesus, he insulted the Jews one last time by fastening a notice to the cross, written in Aramaic, Latin, and Greek, that he knew would offend them: "Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews." They objected, of course: "Don't write 'The king of the Jews,' but that this man claimed to be king of the Jews."

With his mockery of the Jews Pilate wrote much more than he ever could have known or imagined, for later believers worshipped Jesus not only as king of the Jews, but as "the king of kings" (1 Timothy 6:15, Revelation 19:16), the "king of the ages" (Revelation 19:3), and "ruler of the kings of the earth" (Revelation 1:5). In this week's epistle Paul writes that Jesus is "seated at God's right hand in the heavenly realms, far above all rule and authority, power and dominion, and every title that can be given, not only in the present age but also in the one to come."

Just what sort of king is Jesus? How does his reign and rule compare with other kings? The readings this week show that king Jesus judges injustice instead of perpetuating it.

|

Jesus before Pilate, "Are you a king?". |

Ezekiel indicts the "shepherds" of Israel who serve themselves and ignore the weak, the injured, the sick, the stray, and the lost. "You have ruled them harshly and brutally" (34:4), he says, and consequently the sheep became prey to hostile predators. God himself will therefore defend the weak and the lost, and judge the sleek and the strong: "I will save my flock and they will no longer be plundered." In echoes of Psalm 100, God will rescue his sheep from fear and slavery and deliver them to safety.

"I will judge between one sheep and another," says Ezekiel 34:22. This is the same message as this week's gospel about a king who sits on his throne judging "all the nations." This king separates the sheep and the goats, blessing some with "eternal life" and consigning others to "eternal punishment," all based upon how they treated the hungry, the thirsty, the stranger, the naked, the sick, and the prisoner.

There's a lot of talk these days about human injustice, but considerably less about divine judgment of injustice. In the readings this week, the just king judges injustice. I've recently read books about two dictator-thugs, Charles Taylor of Liberia (And Still Peace Did Not Come: A Memoir of Reconciliation, 2011) and Robert Mugabe of Zimbabwe (The Fear; Robert Mugabe and the Martyrdom of Zimbabwe, 2011). It's hard to fathom the evil that these psychopaths have inflicted on their citizens: systematic rape, economic plunder, torture of political opposition, and crimes against humanity. I take solace in hoping that Taylor and Mugabe will be held accountable for their atrocities.

And what about such divine judgment of human injustice? Thank goodness, judgment belongs to God alone. Maybe the love of God and justice become intolerable for some people — they alone lock the doors of hell from the inside. Further, divine judgment is not merely retributive but also redemptive. The early church fathers Origen and Gregory of Nyssa even hoped for the redemption of satan. And most important of all, since divine judgment begins with God's people (1 Peter 4:16–18), when we think of judgment we shouldn't focus on Taylor or Mugabe; we should think about our own selves.

Image credits: (1) Blogspot.com; (2) Britannica.com; and (3) DudhatArtGallery.com.