Discerning Divine Judgment

For Sunday February 19, 2012

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year B)

2 Kings 2:1–12

Psalm 50:1–6

2 Corinthians 4:3–6

Mark 9:2–9

I don't know who wrote the footnotes for the New Oxford Annotated Bible (1991), but I was startled to read their description of Psalm 50 for this week. The editors call Psalm 50 "A Liturgy of Divine Judgment." Wow, I thought, a liturgical service focused on God's judgment. When you read Psalm 50, though, you see that the description fits.

|

The "Mighty One" summons heaven above and earth beneath "that he may judge his people." This isn't a judge you'd want to face, for "a fire devours before him, / and around him a tempest rages." Indeed, "God himself is judge." Witnesses are called, testimony is given and a warning issued: "I will rebuke you and accuse you to your face. / Consider this, all you who forget God, / or I will tear you to pieces, with none to rescue."

This psalm places us in dangerous territory. It defies easy explanation, and evokes deeply ambivalent feelings. Who could be so presumptuous as to portray God as a monster and to invoke divine judgment? History is littered with the horrific consequences of this dark human impulse (see below). And yet who wants to live in a world where human injustice never meets divine accountability? Do the vulnerable and the oppressed have no hope for redress for how the violent and the powerful have dehumanized them?

So, we're rightly reluctant to invoke God's judgment, even if the psalmist does so, yet at the same time we viscerally long for such judgment, and so find solace in Psalm 50.

|

I recently read an article by Adam Gopnik in the New Yorker about the Spanish Inquisition. Gopnik's article, called "Inquiring Minds" (January 16, 2012), reviews the new book by Cullen Murphy called God's Jury: The Inquisition and the Making of the Modern World (2012). The Inquisition combined fanaticism, torture and "bureaucratic brutality" that culminated in the infamous autos-da-fé — public liturgies of divine judgment, if ever there was one. "We know the cruellest of fanatics," writes Gopnik, "by their exceptionally clear consciences." They were God's jury, doing his business.

It would be hard to be too hard on the church's inquisitions. But as Murphy shows, its secular counterparts don't get a free pass. The sub-title of his book suggests its unique contribution. Murphy argues that the Inquisition did not spell the end of modernity but its beginning. The Inquisition is not a bygone relic of medieval history that we've outgrown, but a living legacy with contemporary heirs: "the Gestapo, the K.G.B., the Stasi. Even our Guantanamo-making apparatus has a forbear in Torquemada and the men in red hats."

|

The Inquisition is only one of many sobering reasons why we should be cautious to speak of God's judgment. Judgment belongs to God alone. Divine judgment is not merely retributive but also redemptive. It's God's penultimate word and not his final word. The early church fathers Origen and Gregory of Nyssa even hoped for the redemption of satan. And Jesus told us not to judge lest we be judged.

Since divine judgment begins with God's people (1 Peter 4:16–18), and since we shall all stand before God's judgment (Romans 14:10), when we think of judgment we should think about our own selves, not about others. Even the apostle Paul contemplated the real and harrowing possibility of his own banishment to perdition (1 Corinthians 9:24–27).

God's judgment acknowledges the disparity between what is and what should be. It's God's persistent refusal to let us sink to our worst impulses and to settle for anything less than his best for us. In judgment God says to us "I will not abandon you to yourself. I will not forget the cries of the oppressed, the weak, the vulnerable, and all those who have suffered at the hands of the violent and the powerful."

|

This is why three books I recently read make me think of judgment as a form of consolation. The memoir by Agnes Kamara-Umunna, And Still Peace Did Not Come: A Memoir of Reconciliation (2011), describes the horrors of life in Liberia under the dictator-psychopath Charles Taylor. Similarly, in his book The Fear; Robert Mugabe and the Martyrdom of Zimbabwe (2011), Peter Godwin returns to his boyhood country and "bears witness" to the national devastation under the world's oldest head of state. Finally, in Dancing in the Glory of Monsters; The Collapse of the Congo and the Great War of Africa (2011), Jason Stearns explains the history of the deadliest war of our generation.

It's very hard to exaggerate the suffering that our fellow human beings have experienced at the hands of despots like Taylor and Mugabe: starvation, disease, systematic rape, economic plunder, torture of political opposition, and crimes against humanity. People fret a lot about human injustice, but say considerably less about divine judgment of injustice. In Psalm 50 for this week God judges injustice.

I like to hope that God the judge says to these tens of millions of innocent victims, "you are not forgotten. Witnesses have testified. One day, I will right these wrongs, and injustice will face judgment." I pray that the atrocities will meet accountability in the Congo, Liberia, Zimbabwe, and the many other places like them.

|

Psalm 50 isn't the only "liturgy of divine judgment" in Scripture, not by a long shot. The Old Testament reading for this week is a case in point. The political panorama of 1–2 Kings includes the reigns of forty kings and one queen (Athaliah in 2 Kings 11). This period covers the 400 hundred years from the death of David to Israel's exile to Babylon in 586 BC. It's a political history of Israel's government, but one told with an interpretive twist, for it's told from the theological perspective of prophetic judgment. And what is the conclusion?

Only two kings received unqualified approval by the narrator (Hezekiah in 2 Kings 18:3 and Josiah in 22:2). With monotonous regularity, over thirty times the narrator renders the ominous judgment that a king "did evil in the eyes of the Lord." Instead of the glorification or celebration of political power, his history of politics is uniformly pessimistic. Once again, we're left with a visceral longing for the judgment of injustice. The conclusion doesn't advise pacifism in the face of evil, but it's a trenchant reminder of where our ultimate hope resides.

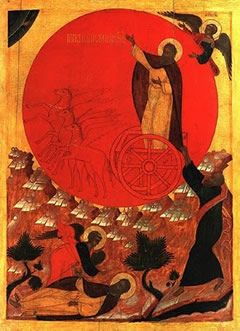

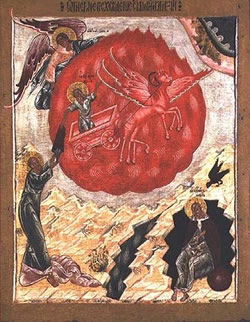

Image credits: (1–5) www.johnsanidopoulos.com;