The Word of the Cross and the Wisdom of the World

For Sunday March 11, 2012

Third Sunday in Lent

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year B)

Exodus 20:1–17

Psalm 19

1 Corinthians 1:18–25

John 2:13–22

When John McCarthy of Stanford University died in October 2011, computer scientists around the world remembered him for his pioneering contributions. Virtually every obituary recalled how McCarthy was the person who coined the term "artificial intelligence" back in 1956. Since a friend at my church specializes in AI, I asked him if he knew McCarthy or had any fun stories about him.

I still remember what John Mark said about McCarthy. After remembering him fondly, he said, "McCarthy did what many scientists in AI do. When they think about how a computer might be 'more human,' they almost always construe that as making a computer smarter. It's like they reduce humanity to rational intelligence, and forget about the many other characteristics that make us human."

|

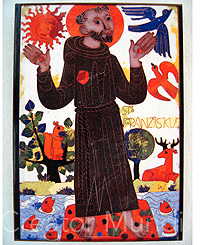

The "holy fool" Saint Francis of Assisi. |

Most of the world's problems are not due to ignorance. We have plenty of smart people. I was reminded of this simple but powerful insight while reading the little book Why Niebuhr Now? by John Patrick Diggins. Reinhold Niebuhr (1892–1971) was arguably the most important American theologian of his generation. He lived through the first world war, the Depression, the second world war, the Holocaust, the Spanish civil war, the Korean war, Vietnam, the landing on the moon, and the Cold War.

Niebuhr insisted that humanity's problems are not ignorance or intelligence but rather the corruption of human nature. We're thus confronted with "the limits of knowledge and the necessity of faith." Niebuhr questioned political, moral, and especially intellectual idealism. As Diggins puts it, "Niebuhr addressed the realities of human affairs and demonstrated that until we consider certain Christian insights about human nature, we can never understand the nature of power in history."

Paul's epistle for this week takes me back thirty years to my seminary days and a philosophy class in which our professor required us to memorize 1 Corinthians 1:18–31. The assignment was a clever pastoral reminder. While we read Plato, Aristotle, and Kant, Paul reminded us that "the message of the cross is foolishness to those who are perishing, but to us who are being saved it is the power of God. . . The foolishness of God is wiser than man's wisdom, and the weakness of God is stronger than man's strength" (1 Cor. 1:18, 25).

We should never disparage human reason. My professor would have been the first to affirm the legitimacy, the pure enjoyment, and especially the Christian obligation to study the intellectual riches of the world, whether in Artificial Intelligence and architecture, law and literature, or engineering and economics. He himself had completed two PhDs by the age of thirty-five. He rightly warned us of the horrible damage done when anti-intellectualism isolated and insulated the church from culture. Simply put, human reason is a divine gift.

Paul engaged the cultural elite of his day in Athens' marketplace of ideas. Once some Epicurean and Stoic philosophers who had ridiculed him as a "babbler of strange ideas" (namely, the resurrection of Jesus) brought him to the famous Areopagus. There Paul joined those who "spent their time doing nothing but talking about and listening to the latest ideas" (Acts 17). Truth is truth, whether sacred or secular, and wherever it is found — in science, poetry, film or in any other human endeavor. Gold from "Egypt" or the Areopagus is still gold, observed saint Augustine.

|

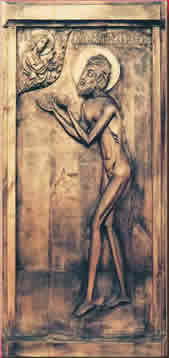

The "holy fool" Saint Basil of Moscow. |

Augustine also observed, though, that however much human reason is a divine gift, revelation is a divine necessity. Antigone by Sophocles provokes us to consider civil disobedience. A Mozart opera touches the depths of human emotion. Photos from the Hubble telescope fill us with cosmic awe at the power of science and the scope of the universe. But however beautiful and true are the fruits of human intelligence, and after we have embraced all that is good and noble in them, there's a Grand Narrative that transcends, transforms, and even subverts it all. It's a Story that's different in kind and not just in degree.

Paul says that knowledge is a form of power that stratifies humanity into social meritocracies and religious hierarchies. The Corinthians confessed their faith in a crucified Christ, a story of divine weakness, foolishness and poverty. But they had transformed it into an occasion for boasting about human power, wisdom, wealth and influence: "I follow Paul," "I follow Apollos," "I follow Peter," and, in the ultimate attempt at one-up-man-ship, "I follow Christ." And so the Corinthian church had fragmented over "boasting" (1:29, 31, 3:21, 4:7) about various claims of superiority.

Paul sharply repudiated all forms of social meritocracy and religious hierarchy. The story of a crucified Christ as the "power and wisdom of God," which story was so repulsive to Jews and ridiculous to Greeks, deconstructs our every lust for power. To make his point, Paul draws upon the personal experiences of both the Corinthians who received the gospel and the apostles who preached it to them.

In an interesting sociological snap shot of the early church, Paul reminds the Corinthians: "Not many of you were wise by human standards; not many were influential; not many were of noble birth" (1:26). People of power and influence rightly understand the gospel as a threat to all that they care about. The sophisticated Athenians "sneered" at his message (Acts 17:32). The downward mobility of Christians was one of the main targets of their critics.

Celsus (fl.175) combined socioeconomic snobbery with intellectual sarcasm to deride Christians: "In some private homes we find people who work with wool and rags, and cobblers, that is, the least cultured and most ignorant kind. Before the head of the household they dare not utter a word. But as soon as they can take the children aside or some women who are as ignorant as they are, they speak wonders." Similarly, in the The Octavius of Minucius Felix, the pagan Caecilius derided Christians as "utter boors and yokels, ungraced by any manners or culture."

After reminding the Corinthians of their origins, Paul described his own apostolic experience (4:9–13): "For it seems to me that God has put us apostles on display at the end of the procession, like men condemned to die in the arena. We have been made a spectacle to the whole universe, to angels as well as to men. We are fools for Christ, but you are so wise in Christ! We are weak, but you are strong! You are honored, we are dishonored! To this very hour we go hungry and thirsty, we are in rags, we are brutally treated, we are homeless. We work hard with our own hands. When we are cursed, we bless; when we are persecuted, we endure it; when we are slandered, we answer kindly. Up to this moment we have become the scum of the earth, the refuse of the world."

|

Holy fool Saint Pelagia and courtesans. |

In his little book A Time to Keep Silence, Patrick Fermor (1915–2011) describes visiting four monasteries while looking for a quiet place to write. He was immediately shocked at the "staggering difference" between life inside the monastery and outside in the world. The vows of poverty, chastity, obedience, stability and community are the exact opposite of the world's infatuation with wealth, promiscuity, independence, freedom, and privacy.

Fermor is candid about his experiences in the monasteries. After a period of intense loneliness, depression, and fitful nights, the hospitality of the monks and the rhythm of their liturgy made a profound impact on this self-described "giaour" or unbeliever. He admits that adapting to monastic life was hard, and it raised many questions. But returning to the vulgarity of the world, he says, was "ten times worse." Which is a poignant reminder of the stark contrasts between the wisdom of the world and what Paul calls the "word of the cross."

For further reflection

* Consider the Christian tradition of "holy fools" which is based upon this Corinthian text.

* Saint Anthony (d. 356): "Here comes the time, when people will behave like madmen, and if they see anybody who does not behave like that, they will rebel against him and say: 'You are mad' — because he is not like them."

* See Stanley Hauerwas and Jean Vanier, Living Gently in a Violent World; The Prophetic Witness of Weakness (Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, 2008), 115pp.

Image credits: 1) CreatorMundi.com; (2) Phil Wyman's Square No More blog; and (3) Amma Guthrie blog.