Our God-haunted World

A guest essay by Marilynne Robinson. Robinson is the author of three novels — Housekeeping (1981), Gilead (2004), which won the Pulitzer Prize, and Home (2008), along with four works of non-fiction. She's lectured at numerous universities, including Oxford and Yale, and written for the Paris Review, Harper's, and the New York Times Book Review. Since 1991 she's taught at the Iowa Writers' Workshop.

For Sunday December 16, 2012

Third Sunday in Advent

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

Zephaniah 3:14–20

Isaiah 12:2–6

Philippians 4:4–7

Luke 3:7–18

God is always present among us to heal and restore. Zephaniah tells us he is in our midst as our savior hero. And in his rescue of us he is rejoicing. “He will rejoice over you with gladness, he will renew you in his love, he will exult over you with loud singing as on a day of festival.” This extraordinary image of divine exultation resonates with the poetry of Creation itself, the moment when “the morning stars sang together and the heavenly beings shouted for joy.” The God described in these verses as a triumphant warrior is the God of compassion in the fact of his triumph: “I will save the lame and gather the outcast, and I will change their shame into praise.”

|

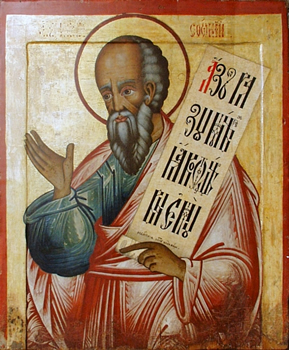

An 18th century Russian icon of the prophet Zephaniah. |

It was biblical Israel’s extraordinary fate to epitomize human life on earth at every scale, as nation, as community, as wandering widow or beleaguered king. The grandest prophecy and the loneliest psalm will tell us that sorrow, which is truly to be lamented, has ended or will end, and the goodness of life will emerge again. The restoration of peace and righteousness is or will be a cause of profound rejoicing.

Yet this assurance seems rather abrupt, coming at the end of Zephaniah’s prophecy. Through most of the text he speaks of disasters so dire that a modern reader might think only very recent generations could have been threatened by them. “I will utterly sweep everything from the face of the earth, says the Lord.” Humans and animals and the birds of the air.

It is our privilege as moderns to know that such a thing might indeed happen. If it does, we will probably be right in attributing it in practical terms to our abuse of the planet, perhaps especially to our propensity for war. Christianity has always proclaimed that God in his grace takes the sins of humankind upon himself, and so he does here when he identifies his justice with the harm humankind has done and is liable to do. We know now that our worst potential sins and their worst consequences are easily within the range of human capability, and that this is true whether there is a God or there is no God and we are alone in the universe to face the blunt effects of all our centuries of greed and malice. At this point in history we have learned that the harshest language of judgment may indeed anticipate our future, and that the hope we live in is an unconscious intuition of an abiding life invested and sustained in this world by its Creator.

The prophets tell us that we are contained in an ethical cosmos. Choices have consequences. These are not, in the overwhelming majority of cases, choices we make as individuals, though in the degree that we are all open to the suasions of fear and hatred, or of greed and oppression, we are guilty of the evils that follow from them. Then the recoil of divine justice is the effect of the very contempt for divine justice that implicates humankind in its own suffering.

But the God of Israel does not leave the matter there. His grace is the sacred difference between the grim story we could tell ourselves about the shadow war of human nature against everything that deserves the name wellbeing, and the story the prophet and the psalmist tell of the new heaven and new earth somehow forever implicit in this wronged and profoundly good Creation. The Lord is in our midst. Rejoice in the Lord always, reads the epistle for this week.

|

Zephaniah addressing people (France, 16th century). |

According to the Christian proclamation, God as man lived quietly in the world for more than thirty years before he called his first disciple, drawing no attention to himself or to his presence with us. His voice was not heard in the street. We must assume that sunlight was no lovelier those thirty years, or time less inexorable. The Romans, who made synonyms of order and desolation, tramped the roads of his holy Judea. If we take it to be true that he walked in the cool of mornings and the breeze of evenings among Adam’s children, who were at no special pains to hide their transgressions from him or to put a gloss of piety on the good they did, and that he saw them sometimes comfort the lame and welcome the outcast, as people will do, then surely he rejoiced in them, and in the unutterable good he intended for them. Still, every day was like any other day through those thirty years, miraculous and God-haunted as the world was in the beginning, is now, and always will be.

The Lord is near. We know not the day nor the hour of his coming because he is with us always, every day and every hour. We can rejoice in the Lord because he first rejoiced in us, and because he has put his mighty blessing on every gentleness we offer one another. Let our gentleness be known to everyone. If there is any excellence and if there is anything worthy of praise, let us think about these things. They are the joy of God. And the peace of God, which surpasses all understanding, will keep our hearts and our minds in Christ Jesus.

Image credits: (1, 2) Wikipedia.org.