When the Trite is Also True

For Sunday January 13, 2013

The Baptism of Jesus

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

Isaiah 43:1–7

Psalm 29

Acts 8:14–17

Luke 3:15–17 (21–22)

Over the Christmas break I started reading David Foster Wallace's novel Infinite Jest (1996). The crazy complexity of the 1100-page story makes it hard to describe. In Infinite Jest, time is subsidized by corporations, as in the "Year of the Tucks Medicated Pad." A terrorist group from Quebec called the "Wheelchair Assassins" wants to attack the United States with a film that's so powerfully entertaining that "whoever saw it wanted nothing else ever in life but to see it again, and then again, and so on."

The novel explores numerous aspects of our culture's Zeitgeist — national character, information overload (which the book mimics), suicide, and addiction to drugs, entertainment, and pleasure. Many passages make you laugh out loud, others stymie you, single paragraphs run on for pages, and the infamous 388 footnotes themselves can have footnotes.

Most of all, says Wallace's biographer DT Max, Infinite Jest is "a story of people in pain." It has a "very quiet but very sturdy and constant tragic undercurrent," writes novelist Dave Eggers, "that concerns a people who are completely lost, who are lost within their families and lost within their nation, and lost within their time, and who only want some sort of direction or purpose or sense of community or love." Wallace often said that he intended his fiction to explore what it means to live a life of human wholeness.

Joelle Van Dyne, for example, a.k.a. Madame Psychosis, is a member of the "Union of the Hideously and Improbably Deformed," whose members wear veils to hide their shame. A failed suicide attempt lands her in Ennet House, a drug and alcohol halfway house. There she meets Don Gately, a former criminal, recovering addict, and current staffer at Ennet House. He's also the only person in a cast of 200-plus characters who's found a way beyond psychic carnage to genuine healing — but not in a way that you'd expect.

|

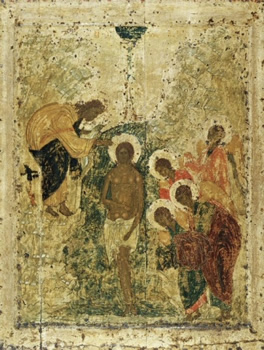

Baptism of Jesus by Andrei Rublev (1405). |

Gately is committed to the AA program, but it drives him crazy. He hates the "corny slogans and saccharine grins and hideous coffee," the "limply improbable cliched drivel," the "goopy sentiment," the cultish "brainwashy elements," and the smug "psychobabbly" jargon — which is "probably just Unitarian happy horseshit." But if you Hang In, and Keep Coming, Gately found, you discover "that the thing actually does seem to work. Does keep you Substance-free. It's improbable and shocking."

Gately discovered that the trite can be true.

"How do trite things get to be true? Why is the truth usually not just un- but ANTI-interesting? Because every one of the seminal little mini-epiphanies you have in early AA is always polyesterishly banal." But experiencing the true within the trite is only for people who out of desperation learn to Keep It Simple and Ask For Help. With his own thirty years of clinical depression, drug addiction, psychiatric hospitalizations, drug regimens, and AA experience, the novel tracks Wallace's real life movement from irony to sincerity.

The addicts at Ennet House distrust pretension. They detest any effort to impress or attempt to perform. They can smell a fake a mile away. "Gately's found it's got to be the truth, is the thing. The thing is it has to be the truth to really go over, here. It can't be a calculated crowd-pleaser, and it has to be the truth unslanted, unfortified. And maximally unironic. An ironist in a Boston AA meeting is a witch in church. Irony-free zone. Same with sly disingenuous manipulative pseudo-sincerity. Sincerity with an ulterior motive is something these tough ravaged people know and fear, all of them trained to remember the coyly sincere, ironic, self-presenting fortifications they'd had to construct in order to carry on Out There."

In the baptism of Jesus we encounter three of the most trivialized words in the English language that are nevertheless true: "God loves you."

Or Isaiah's poetry for this week: "Fear not for I have redeemed you; / I have called you by name; you are mine."

After living in total obscurity for thirty years, Jesus left his family and joined the movement of his eccentric cousin John. He might have even submitted himself to John as a disciple to a mentor. This much is clear — John the Baptizer was a prophet of radical dissent, so much so that his detractors said he had a demon. Whereas his father was a priest in the Jerusalem temple, John fled the comforts and corruptions of the city for the loneliness of the desert. There he dressed in animal skins and ate insects and wild honey.

Then comes a shock — Jesus asks to be baptized by John. With some important stylistic differences, all four gospels tell the story of Jesus's baptism by John: "When all the people were being baptized, Jesus was baptized too. And as he was praying, heaven was opened and the Holy Spirit descended on him in bodily form like a dove. And a voice came from heaven: 'You are my Son, whom I love; with you I am well pleased.'"

After his radical rupture with his family and conventional society by identifying with the desert troublemaker, to the point of submitting to his baptism, Jesus's own family tried to apprehend him. The villagers of his home town of Nazareth tried to kill him as a deranged crackpot.

Why did Jesus ask for John's "baptism of repentance?" The earliest believers asked this question, because in Matthew's gospel John the Baptizer tried to deter Jesus: "Why do you come to me? I need to be baptized by you!" In other words, John insists that Jesus was not getting baptized for his own sins. Crossan argues that there was an "acute embarrassment" about Jesus's baptism on the part of the gospel writers. Even a hundred years after the event, Jesus's baptism made some Christians feel uneasy. In the non-canonical Gospel of the Hebrews (c. 80–150 AD), Jesus denies that he needs to repent. He seems to get baptized to please his mother.

|

Chinese porcelain, early 18th century. |

We get clues to this question if we back track to the beginning. Matthew's genealogy includes forty-two men, but also four women with unsavory histories. Tamar was widowed twice, then became a victim of incest when her father-in-law Judah abused her as a prostitute. Rahab was a foreigner and a whore who protected the Hebrew spies by lying. Ruth was a foreigner and a widow, while Bathsheba was the object of David's adulterous passion and murderous cover-up. These four women are part of Jesus's family of origin.

The story continues when pagan magi worship the baby Jesus. Jesus then escapes to Egypt, the symbolic enemy of Israel, and finds refuge there. At the baptismal scene there are soldiers and tax collectors of the Roman oppressors.

Jesus's baptism inaugurated his public ministry by identifying with "the whole Judean countryside and all the people of Jerusalem." He allied himself with the faults and failures, the pains and problems, of all the broken people who had flocked to the Jordan River. By wading into the waters with them he took his place beside us and among us. Not long into his public mission, the sanctimonious religious leaders derided Jesus as a "friend of gluttons and sinners." They were right about that.

With his baptism, Jesus openly and decisively stands with us in our brokenness.

Jesus's baptismal solidarity with broken people was vividly confirmed by God's affirmation and empowerment. Still wet with water after his cousin had plunged him beneath the Jordan River, Jesus heard a voice and saw a vision — the declaration of God the Father that Jesus was his beloved son, and the descent of God the Spirit in the form of a dove. The vision and the voice punctuated the baptismal event. They signaled the meaning, the message and the mission of Jesus as he went public after thirty years of invisibility — that by the power of the Spirit, the Son of God embodied his Father's unconditional love of all people everywhere.

God loves me. He knows my name. Yes, it's "improbable and shocking." But as Don Gately learned, if your're willing to move from clever sophistication to genuine sincerity, "You're encouraged to keep saying stuff like this until you start to believe it."

Image credits: (1) Terminartors.com and (2) Wikipedia.org.