"It's a Gift"

One Body, Many Parts

For Sunday January 27, 2013

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

Nehemiah 8:1–3, 5–6, 8–10

Psalm 19

1 Corinthians 12:12–31a

Luke 4:14–21

During my four years as a visiting professor at Moscow State University (1991–1995), our family attended the Moscow Protestant Chaplaincy. The MPC was founded in 1962 by the National Council of Churches to minister to the American Embassy community in Moscow. In fact, the church was located on the embassy grounds, and the pastor received state department housing. For thirty years the MPC was a cozy, little community with an awkward relationship. Some people objected to a church in an embassy. Security concerns made it difficult to bring outsiders into the embassy for worship.

A church called to be radically inclusive became very insular. But then two things happened.

After a fire at the embassy in 1990, the government kicked the church out — they needed every square inch of space during repairs. So the MPC found its own space and place in central Moscow. Then, on December 24, 1991, Mikhail Gorbachev resigned and the Soviet Union vanished. In the wake of the collapse, the whole world poured into Moscow.

|

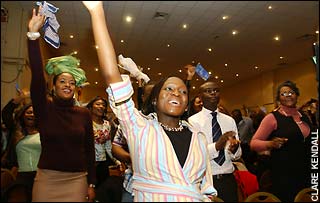

No longer isolated in and restricted by the embassy, the MPC grew to about 200 people from 30 nations and 20 denominations. Half the church was composed of refugees, and African university students who were stranded after their Soviet scholarships evaporated. The other half of the church included business executives, NGO people, personnel from embassies around the world, missionaries, and a few Russians. The bureau chiefs from NBC and CBS were regulars — so much for the "secular" media.

One Sunday our pastor visited the British Anglican church. He returned with a tongue-in-cheek report: "I have good news and bad news. The good news is that everyone at St. Andrew's is white. The bad news is that everyone at St. Andrew's is white!" There was an important point to his jest. It felt good to be among people like yourself. But he also missed the radical diversity of the MPC.

In seminary thirty years ago we studied the "homogeneous unit principle" articulated by the missiologist Donald McGavran of Fuller Seminary. If you expect people to convert and churches to grow, said McGavran, you must appeal to a common denominator around which they can gather — ethnicity, language, level of education, and so on. And homogeneity is what we mainly see when we look at churches — black Pentecostals enjoy their lively worship, Episcopalians prefer their quiet formality, some people like the organ, others like praise bands, and never the twain shall meet.

For McGavran, homogeneity is good and necessary. But for H. Richard Niebuhr of Yale, homogeneity signals failure. In his book The Social Sources of Denominationalism (1929), Niebuhr said that denominations formed not around theological distinctives but because of shared sociological factors — race, ethnicity, economic status, etc. McGavran saw this as a reasonable concession to human nature — birds of a feather flock together. Niebuhr said it demonstrated that the church was more like a thermometer than a thermostat; instead of transforming society, the church conformed to culture. A cynic might say that Sunday at 11am is the most segregated hour in America.

With few exceptions, society prizes conformity and punishes differences. The Japanese have a proverb for this: the nail that sticks out gets hammered down. None of us are immune from these pressures, but we can choose how we respond to them.

Last week I read John Schwartz's memoir called Oddly Normal (2012). It tells how his family struggled to help their son Joseph accept that he's gay. The book is a powerful reminder of how hard it is to be different. Joseph was not only gay. He was also extremely smart, physically clumsy, and socially awkward. He needed help from psychological, occupational, and speech therapists. After conflicting advice, his parents decided that Joseph fit a diagnosis called PDD-NOS: Pervasive Developmental Disorder – Not Otherwise Specified.

|

And, of course, kids can be cruel. Every family experience is different. School bureaucracies can be complicated. Scientific research is often inconclusive. Experts disagree about diagnoses and treatments. As Joseph became increasingly isolated, both socially and emotionally, he internalized the rejection he experienced because of his differences. He edited, hid, and then rejected his different self by attempting suicide at the end of the seventh grade.

In the epistle this week Paul calls us to a better way of dealing with our differences. He compares the church to the human body; although it's made up of many different parts, it forms one body. And so it is with us. Despite our obvious and many differences, God calls us to a unity that's not bland uniformity, and to a diversity without division. To three different churches Paul writes, "There is no Greek or Jew, circumcised or uncircumcised, Scythian, slave or free, male or female, but Christ is all, and is in all."

Paul draws some practical conclusions about our unity in diversity. I need you. And you need me. "The eye cannot say to the hands, 'I don't need you!' And the head cannot say to the feet, 'I don't need you.'" Paul subverts our normal human tendencies: "Those parts of the body that seem to be weaker are indispensable, and the parts that we think are less honorable we treat with special honor." Despite our differences, we should have "equal concern for each other."

Schwartz tells how he was helped by a gay friend who related his own story about a college experience. One day Brian was talking about a writing project with his professor, Betty Sue Flowers (who later ran the LBJ Library and Museum), and happened to mention that he was gay. He was shocked by her response: "It's a gift," said Flowers.

"I would have never thought of that as a possible reply," said Brian. "Yet I immediately knew exactly what she meant. Because I was different, I would see things differently than everyone else, and that would be valuable to me in ways that I would only discover over time. I don't think it's too much to say that her words changed how I looked at my life."

The greatest gift you can give to the church and the world is to be yourself. Nobody else can do that. And reciprocally, to extend the same grace to others: "accept one another, just as Christ accepted you" (Romans 15:7).

Image credits: (1) The Telegraph and (2) Knights of Divine Mercy.