"This Man Welcomes Sinners"

For Sunday March 10, 2013

Fourth Sunday in Lent

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

Joshua 5:9–12

Psalm 32

2 Corinthians 5:16–21

Luke 15:1–3, 11b–32

In the fall of 2003 I spent two weeks in Oxford doing some research and writing. One Sunday morning I walked down to Saint Aldates Church on Pembroke Street in the center of town. No one knows for sure who Saint Aldates was, but the church's first rector, Reginald, started serving the church in 1226. As I walked into St. Aldates, the usher enthusiastically greeted me, “We welcome all sinners!"

Those were words I needed to hear. They summarize the mission of Jesus: ”I have not come to call the righteous, but sinners.” They also echo the accusation of his enemies in this week's gospel: “this man welcomes sinners and eats with them.”

Jesus made a lot enemies in a short time. Broadly speaking, his detractors fall into two categories — the politically powerful (Rome), who executed Jesus, and the religiously self-righteous, who are the subject of this week's gospel.

|

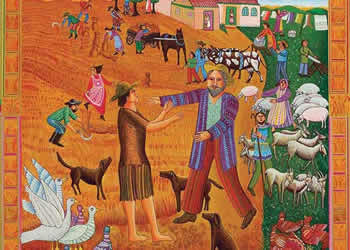

Prodigal Son by John August Swanson. |

The gospels tell how Jesus violated rituals of religious purity and ate with “many” sinful people, and how “there were many sinful people who followed him.” This large following of moral outcasts felt safe with Jesus, sheltered rather than judged. His identification with them was a central rather than a peripheral characteristic of the kingdom that he announced, so much so that his enemies dismissed him as a drunkard and a glutton.

When questioned why he befriended these "dirty" people, Jesus was unapologetic: ”It's not the healthy who need a doctor, but the sick."

There's a whole group of parables that emphasizes that God welcomes sinners. As Joachim Jeremias observes in his book The Parables of Jesus (1972), these parables have a unique characteristic — they're all addressed directly to the enemies of Jesus. These parables don't merely announce the good news, they also vindicate it. “They are a controversial weapon against the critics and foes of the Gospel," says Jeremias, "who are indignant that Jesus should declare that God cares for sinners."

Some of the parables describe what sinners are like. They're sick and needy, vulnerable in a world that prizes power and religious righteousness. Jesus says that these outcasts understand God better than the insiders.

In the parable of the Two Sons, Jesus says that tax collectors and whores will enter the kingdom of God before the chief priests and elders. Why? Because they know their brokenness and thus their need for repentance. True prodigals have no pretensions. They're like a son who initially refused to obey, but then later did obey. Jesus's opponents did the opposite; they pretended to obey but really didn’t.

Similarly, in the parable of the Two Debtors, during a dinner a harlot stood behind Jesus weeping, wiping his feet with her hair, and anointing him with perfume. In her brokenness she disregarded all social propriety in order to express her profound gratitude.

When the host objected, Jesus told a parable about two debtors, one who owed a huge sum and another a small sum. Both were forgiven, but the former was more grateful. Then Jesus drew a sharp contrast. The immensity of the woman’s sin led to unbounded gratitude when it was forgiven, but the self-righteous host was rebuked because he hadn't shown Jesus the least sort of grateful attention.

Needy people know repentance; they're grateful when helped. The religiously righteous often don’t know much about repentance or gratitude, for they've never even imagined their own poverty of spirit.

A second group of parables invites Jesus's self righteous detractors to consider what they themselves are like. In the parable of the Two Sons they're like a child who didn't do what he promised. In the parable of the Tenants, Jesus compared his opponents to tenants who humiliated the owner of a vineyard and then murdered his heir. In the parable of the Wedding Feast he said they're like socially respectable people who reject a royal invitation with pathetic excuses. Why do they scorn sinners who do accept the invitation?

|

Return of the Prodigal by Rembrandt. |

In one of his most caustic attacks in all the gospels, Jesus strings together a series of word pictures for this sort of religious hypocrisy. His religiously righteous enemies, he said, were like blind guides, filthy cups, whitewashed tombs, unmarked graves (a source of impurity), and poisonous snakes. These loveless people are not the sort of people you would want to meet if you understood yourself as a needy and vulnerable sinner.

Then there are the parables that describe what God is like. The story of the Prodigal Son was told to those who complained that “this man welcomes sinners and eats with them." We're familiar with this story about a son who shamed his family by asking for his inheritance, who squandered it all in hedonistic excess, then found himself on skid row eating pig food. But as we just saw, people who hit rock bottom often know quite a bit about repentance, and this man “came to his senses.” While the son was still far off, the father, utterly undignified for the Orient, ran to him and embraced him. Instead of treating him as a hired hand, as the son had requested, he celebrated him as an honored guest — with a robe, a ring and a party.

Why does Jesus eat with sinners? Because that's what God is like. He's good and gracious. He loves without conditions or limits. He's full of compassion for us in the midst of our brokenness. He pays a full day's wages for one hour of work.

But watch out for the religiously righteous. They can be like the elder brother who resented his father’s lavish grace, or like Jonah who complained when the Ninevites repented and God forgave them. Many people, Jesus warns us in another parable, are “confident of their own righteousness and look down on everybody else.” Some people have a need to be right, and to be seen as being right.

In the epistle this week, Paul says that "God gave us this ministry of reconciliation." Do real sinners feel really welcome in our churches?

And here's a radical idea — extend this divine mercy to your own self, for that's what God has already done.

Much of the poetry of Gerard Manley Hopkins (1844–1889) is characterized by darkness and despair, reflecting his lifelong interior struggles. After converting to Catholicism, which estranged him from his Anglican family, Hopkins burned much of the poetry he had written, and even stopped writing for seven years. After ordination as a Jesuit priest, an assignment in Ireland left him feeling isolated and melancholy, thus giving rise to his so-called "terrible sonnets."But somewhere in his darkness, Hopkins felt God's light. He moved beyond self-reproach to divine acceptance. In one of my favorite poems, My Own Heart, he describes an interior conversation about accepting "God's smile" upon his life.

My own heart let me more have pity on; let

Me live to my sad self hereafter kind,

Charitable; not live this tormented mind

With this tormented mind tormenting yet.

I cast for comfort I can no more get

By groping round my comfortless, than blind

Eyes in their dark can day or thirst can find

Thirst's all-in-all in all a world of wet.Soul, self; come, poor Jackself, I do advise

You, jaded, let be; call off thoughts awhile

Elsewhere; leave comfort root-room; let joy size

At God knows when to God knows what; whose smile

's not wrung, see you; unforseen times rather — as skies

Betweenpie mountains — lights a lovely mile.

Accept one another. And accept that God accepts you.

Image credits: (1) Calvin College and (2) Wikipedia.org.