"My Name Is Legion"

Seeing Ourselves in the Gerasene Demoniac

For Sunday June 23, 2013

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

1 Kings 19:1–4, (5–7), 8 –15a or Isaiah 65:1–9

Psalm 42 and 43, or Psalm 22:19–28

Galatians 3:23–29

Luke 8:26–39

The gospel this week about the Gerasene demoniac reads like an x-rated story.

A nameless man has been exiled to the margins of human existence. He's filthy naked in public. He can't control his speech. He's so violent that people can't come near him. All attempts to restrain him have failed. He exhibits the most common form of self-harm even today — self-mutilation. The etiology of the day added it all up and called it demon possession.

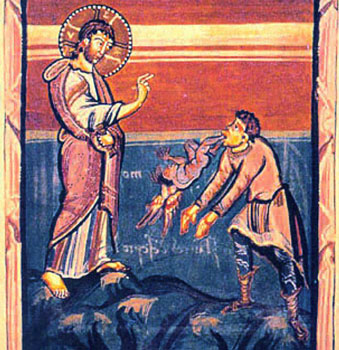

|

Medieval book illustration. |

"My name is Legion!" this homeless man screamed, "for we are many." Tortured in body, mind, and spirit, he embodied the gamut of human suffering, for a Roman "legion" consisted of 5,000 soldiers.

And so his community did what we still do today. They banished the man to the safe and solitary margins of society.

The story is so disturbing that Matthew's condensed version doesn't even mention that Jesus healed the man. Rather, all three synoptics focus on the people's fear of Jesus and their anger at their economic loss. When they saw this derelict man completely healed, and the drowned pigs, "all the people of the region of the Gerasenes asked Jesus to leave them, because they were overcome with fear."

Nothing comes easier than "demonizing" another person. The Stanford anthropologist René Girard spent his distinguished career describing mimetic desire and the scape-goat mechanism to control social violence.

|

Bronze sculpture by C. Malcolm Powers. |

If we're honest, each one of us could say, "My name is Legion." We're a mysterious mixture of genetics, geography, family of origin, personal choices, and God's providential care. Our wisest guides insist that there are so many things we don't understand about ourselves. “I do not understand what I do,” Paul confessed to his readers in Rome.

Back in the fourth century, John Cassian traveled from his home in Romania to Bethlehem, where he joined a monastery. From Bethlehem he made two extended visits to the monasteries of Egypt. He then moved on to Constantinople. Cassian later settled back in Marseilles, founded two monasteries, and wrote three books. His Conferences and Institutes chronicle the riches of early monasticism based upon his personal experiences, and in so doing they transplanted that monastic influence to the West.

Cassian is full of praise for the monks, but he's also remarkably candid. Just what did they discover when they fled the corruptions of the city to the lonely interior of the desert? They experienced a raging battle in the geography of the human heart, a veritable "legion" of voices.

|

15th-century woodcut. |

Cassian wonders aloud, "Why is it that superfluous thoughts insinuate themselves into us so subtly and hiddenly when we do not even want them, and indeed do not even know of them, that it is very difficult not only to cast them out but even to understand them and to catch hold of them?"

That's only the beginning. Here's a laundry list of maladies that I underlined in his books — lethargy, sleeplessness, bad dreams, impulsive urges, self-justification, self-deception, seething anger about trivial matters, sexual fantasies, pious pretense that masks as virtue, clerical ambition, crushing despair, confusion, wild mood swings, flattery, and lust.

And these are only those symptoms that we know: "There are many things that lie hidden in my conscience which are known and manifest to God, even though they may be unknown and obscure to me."

Cassian admits these things, he says, "without any obfuscating embarrassment." Nor does he ever "despise anyone in belittling fashion" for their frailties. These monks were brutally realistic about "the flighty wandering of the human mind," and unfailingly tender because of it.

|

10th-century carved ivory, Milan. |

Mother Teresa's book Come Be My Light (2007) shocked people with its descriptions of profound spiritual darkness that haunted her for fifty years. She writes that she didn't practice what she preached, and laments the stark contrast between her exterior demeanor and her interior desolation: "The smile is a big cloak which covers a multitude of pains… my cheerfulness is a cloak by which I cover the emptiness and misery… I deceive people with this weapon."

She describes the absence of God's presence in many ways — as emptiness, loneliness, pain, spiritual dryness, or lack of consolation. "There is so much contradiction in my soul, no faith, no love, no zeal… I find no words to express the depths of the darkness… My heart is so empty… so full of darkness… I don't pray any longer. The work holds no joy, no attraction, no zeal… I have no faith, I don't believe." She rebukes herself as a "shameless hypocrite" for teaching her sisters one thing while experiencing something far different.

"Where is your God?" taunts the cynic in this week's psalm.

"Lord, why have you forgotten and rejected me?" begs the psalmist.

"I've had enough," says Elijah.

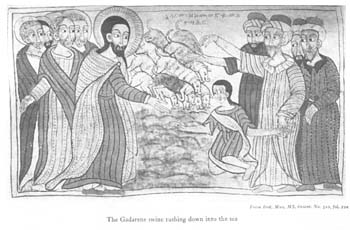

|

13th century Ethiopia, Kebra Nagast. |

When Jezebel threatened to murder Elijah, he rightly feared for his life. After retreating into the desert with a death wish, angels rescued him and sent him back to Horeb, to "the mountain of God." There he entered a cave where "the word of the Lord" spoke to him.

God spoke to Elijah, but not like he expected. Standing on Horeb, a "great and powerful wind" blasted the mountain and shattered the rocks, "but the Lord was not in the wind." An earthquake shook the earth, "but the Lord was not in the earthquake." Fire scorched the land, "but the Lord was not in the fire."

After these dramatic acts of nature, "there came a gentle whisper."

In that faint but discernible whisper God spoke to Elijah. And perhaps that's how he speaks to us today in our own extremities. "Do not fear, I am with you. You are mine. I have called you by name."

Image credits: (1) Wikipedia.org; (2) C. Malcolm Powers, Bronze Sculptor; (3) DevilsPenny.com; (4) Bible.Info; and (5) Sacred-Texts.com.