Not Peace But Division:

The Embarrassing Words of Jesus

For Sunday August 18, 2013

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

Isaiah 5:1–7 or Jeremiah 23:23–29

Psalm 80:1–2, 8–19 or Psalm 82

Hebrews 11:29–12:2

Luke 12:49–56

When the American writer Will Durant tried to identify the historically authentic Jesus, he used what he called a "criterion of embarrassment." Simply put, it's hard to see why writers would fabricate embarrassing material that hurts their cause. We hide embarrassing stories, we don't publish them for posterity. Durant gave examples like Peter's denial and the flight of the disciples when Jesus was arrested.

I would include this week's gospel as another embarrassing example of the authentic Jesus:

“I have come to bring fire on the earth, and how I wish it were already kindled! But I have a baptism to undergo, and what constraint I am under until it is completed! Do you think I came to bring peace on earth? No, I tell you, but division. From now on there will be five in one family divided against each other, three against two and two against three. They will be divided, father against son and son against father, mother against daughter and daughter against mother, mother-in-law against daughter-in-law and daughter-in-law against mother-in-law.”

|

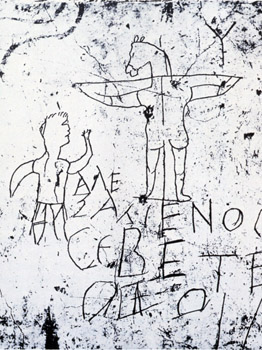

Anti-Christian graffiti c.225; crucified Jesus with donkey's head: "Alexamenos worships [his] God." |

These are harsh words, but hardly an exception. Upon his birth, Simeon prophesied that Jesus would be "a sign of contradiction."

Jesus was rejected by his home town of Nazareth. His family tried to apprehend him as insane. His brothers didn't believe in him. The people of Capernaum ran him out of town. A Samaritan village wouldn't even let him enter their town. His detractors said he was demon-possessed and "raving mad." The religious elite "opposed him fiercely." Many of his disciples quit following him. Rome executed him because people said that he told them not to pay their taxes.

So much for our safe-n-soft version of Jesus.

This harsh opposition to a divisive Jesus reverberates throughout the New Testament.

Peter describes Jesus as "the stone of stumbling and the rock of offense."

Paul called him "a stumbling block to Jews and foolishness to Gentiles."

In John, Jesus prays for his followers: "I have given them your word and the world has hated them, for they are not of the world any more than I am of the world."

The epistle of Hebrews confirms that prayer. The cry of the psalmist this week summarizes the message of the epistle: "You have made us an object of derision to our neighbors, and our enemies mock us."

The recipients of Hebrews were second-generation believers. The text's elegant Greek, its quotations from the Greek translation of the Hebrew Old Testament (LXX), and its distinctly Jewish themes all suggest that the readers were Hellenistic Jewish believers.

Its date is early enough that the author refers to the priesthood and temple sacrificial practices in the present tense. It's hard to imagine a date after 70 AD since it never mentions the catastrophic destruction of the Jerusalem temple. It's also early enough that the recipients believed in the imminent return of Jesus, a belief that turned out to be wrong and therefore gradually waned as the decades receded.

Its date is late enough for the readers to have experienced severe trials and tribulations, a situation that was not the case until several decades after Jesus. The author describes how the believers experienced the confiscation of their property, imprisonment, public insults, persecutions, the discontinuation of their meetings (presumably out of fear of the authorities), and a "great contest in the face of suffering."

When a fire broke out in Rome on June 18, AD 64 and destroyed about half the city, the psychopathic emperor Nero deflected criticism by blaming the Christians. Connecting these dots leads me to conjecture that Hebrews was written during a narrow window of time, after the fire in Rome in 64 AD and before the destruction of the temple in 70 AD. The context was one in which believers faced significant opposition for following the divisive Jesus.

Imprisonment and government confiscation of property corroded community morale. Some people stopped meeting together. These beleaguered believers were tempted to "shrink back," to deny the faith, and to "throw away" their confidence. The author thus encouraged them to "draw near," and to persevere in "full assurance of faith" and "unswerving hope." In particular, he exhorted them to imitate the faith of the saints who had gone before them.

A Christian who had lost house and home, endured public ridicule, or saw a loved one mauled to death in the Circus Maximus might ask many hard questions about God's promises. Does God keep his promises? Exactly what does he promise? And what does it mean to believe God's promises? God's promises loom large in Hebrews 10 and 11. In fact, the word "promise" and its derivatives occur at least ten times in those two chapters.

I've typically read Hebrews 11 as a hall of fame of spiritual super stars. True, it honors saints who "conquered kingdoms, shut the mouths of lions, and quenched the fury of flames." But the author makes two remarkably candid admissions.

When I read more carefully, I discover a different sort of saint. Alongside those who "gained what was promised" (11:33), there were many saints who "did not receive what had been promised" (11:13, 39).

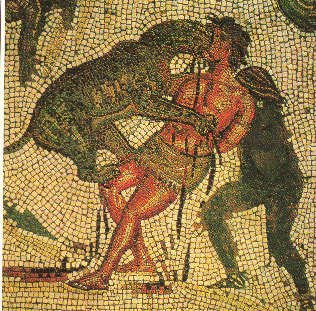

|

Early Christian martyrdom. |

Here's how Hebrews describes the latter saints: "Others were tortured… some faced jeers and flogging, while still others were chained and put in prison. They were stoned; they were sawed in two; they were put to death by the sword. They went about in sheepskins and goatskins, destitute, persecuted and mistreated — the world was not worthy of them. They wandered in deserts and mountains, and in caves and in holes in the ground. These were all commended for their faith, yet none of them received what had been promised."

This isn't rhetorical exaggeration; it could easily describe the life of a Christian under emperors like Nero or Diocletian, or modern despots like Hitler, Stalin, Mao, or Saddam Hussein.

These exemplars of faith remained sure of what they hoped for but did not see, certain of what God had promised but they did not experience: "This is what the ancients were commended for" (11:2).

Abraham is the most important example of how believing isn't seeing. Abraham journeyed from a present clarity to a future of profound ignorance. He journeyed from what he had to what he did not have, from the known to the unknown, from everything that was familiar to all things strange.

Thus Hebrews commends his radical obedience to God, which defied both the inner propensities of human nature and the outer pressures of cultural conformity: "By faith Abraham, when called to go to a place he would later receive as his inheritance, obeyed and went, even though he did not know where he was going. By faith he made his home in the promised land like a stranger in a foreign country."

Abraham died "without having received the promise" (11:13). In the words of Edwin Muir's poem Abraham, "The Promise had not come, and he left his bones, / Far from his father's house, in alien Canaan." With the stuff of his human life unfinished and the promises of God unfulfilled, Abraham became "the father of us all" (Romans 4:16).

Image credits: (1) Utah State University and (2) Benevolent Baptist blog.