Death, Thou Shalt Die

For Sunday April 20, 2014

Easter Sunday

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year A)

Acts 10:34–43 or Jeremiah 31:1–6

Psalm 118:1–2, 14–24

Colossians 3:1–4 or Acts 10:34–43

John 20:1–18 or Matthew 28:1–10

A guest essay by novelist Ron Hansen. Ron's many books include Exiles (2008) and A Wild Surge of Guilty Passion (2011). Among his many honors are a Guggenheim Foundation grant, an Award in Literature from the American Academy and National Institute of Arts and Letters, two grants from the National Endowment for the Arts, and a three-year fellowship from the Lyndhurst Foundation. He is currently the Gerard Manley Hopkins, S.J. Professor in the Arts and Humanities at Santa Clara University, where he earned an M.A. in Spirituality in 1995.

Some years ago I undertook a thirty-day, silent retreat with the Spiritual Exercises of Ignatius Loyola at Easternpoint, Massachusetts. After more than three weeks of prayer and reflection on the Mystery of God and the life of Christ, I was challenged to imagine the gruesome crucifixion of Jesus and his being laid in the tomb. My exercise for the next day was to use five hour-long prayer periods to meditate on Holy Saturday, when Jesus is dead.

|

The Entombment of Christ by Caravaggio (1603). |

Those meditations, I felt, did not go well. The following morning I reported to my Jesuit spiritual director that I hadn’t been able to focus or pray, that I found myself so depressed, spent, and filled with longings, loneliness, and grief that all I could do was lie on my bed and listen over and over again to Mozart’s gorgeous Ave Verum Corpus, in which the composer so sorrowfully contemplates Jesus hanging on the Cross.

Rather mystified, my spiritual director considered my confession of failure at prayer and smiled as he said, “Don’t ask for a grace without expecting to get it!” And I realized that I had been privileged with the exact feelings of dejection and loss that the disciples of Jesus experienced after witnessing from afar their Lord’s crucifixion, his public ministry ended ignominiously.

With the traitorous Judas having hanged himself, the other eleven apostles seem to have stayed in hiding, “mourning and weeping” in the upper room where they’d joined in a Passover supper with Jesus, still fraught with worries for their own lives and despondent over grand hopes that had been vanquished by jealousy, vindictiveness, and misunderstanding. But Mary of Magdala, Mary, the mother of James and John, and, in Luke’s gospel, Joanna, went to Joseph of Arimathea’s own lavish tomb to anoint Jesus’s corpse with spices, only to find that he was risen from the dead just as he’d predicted would happen.

Christ’s resurrection continues to be, of course, a one-of-a-kind incident, and Easter is the preeminent occasion to explain its factual certainty and its importance to Christianity, for there are still so many who consider it either a deception, a wistful metaphor, or just a faith event unsupported by evidence.

Saying that Jesus has risen from the dead does not mean that his noble spirit continued to inspire his disciples while his body remained in the tomb to decay. Easter morning is not merely about a spiritual resurrection in which Christ’s truth, his teachings, and the high points of his life on earth pervade the memories of his friends. The Resurrection of Jesus means that a Jewish man of flesh and blood entered into an otherworldly form of existence, one unrestricted by time, place, or death. Yet in his risen state Jesus is still the same healer and teacher we encounter in the gospels, but now he is perfected in his whole being and purpose and guarantees that through fidelity to him we can achieve our own resurrection and life eternal with our Heavenly Father.

Earlier in the gospels the daughter of Jairus, the son of the widow of Nain, and Lazarus were all resuscitated by Jesus soon after their physical deaths, but the scriptures omit any further mention of them, so presumably they survived until, in the fullness of time, they died as we all will.

She is called Mary of Magdala in Luke’s gospel and Mary Magdalene in the other three. In Matthew, Mark, and Luke she goes to the tomb or sepulcher with other women, but she is alone in John’s gospel when she encounters Jesus just outside the tomb but thinks he is a gardener.

She calls him Sir (Kyrie) and asks where the body of Jesus has been taken. Jesus simply says, “Mary,” and in that familiarity, in the tone and inflection of his voice, she recognizes Jesus in his risen form, and in surprise and joy Mary Magdalene says in Aramaic, “Rabbouni,” or Teacher. Meaning she was, like the Twelve, his student, his disciple.

|

The Resurrection by

Francesco Buoneri (1619–1620). |

Mary Magdalene is the first of his friends to encounter the risen Jesus face to face, and she reported it to others. For that reason she is called “Apostle to the Apostles.” Messenger to the messengers.

Women, we must remember, were not admissible as legal witnesses according to Jewish law. The fact that all the gospel accounts have women discover the empty sepulcher would therefore be odd, even nonsensical, if the new followers of Christ were trying to fake what happened.

If the empty tomb is a late fiction invented by Christians to express faith in Jesus’s ongoing life within them, why would it be framed almost exclusively in terms of women witnesses rather than Peter, James, and John, or the other early leaders of the Church?

Were these women so pointedly there in the tradition precisely because that was what happened, and they could not be removed from the accounts?

In Matthew’s retelling of the resurrection he reports the rumor still present as he wrote his gospel around the years 80 or 90 — that some disciples stole Christ’s body from the tomb. But what advantage would the disciples have in doing that? Would they invent a story of a revived and renewed Jesus knowing it could only lead them to the same fate of crucifixion that their master suffered? And how much conviction would they have had if they’d been forced to lie about what transpired? Would all the preaching, the journeys, the confrontations with authorities, the martyrdoms have taken place if the Apostles’ stories were fundamentally fraudulent?

We accept then in faith that Jesus was raised, as from sleeping to waking, from an earthly mode of existence to that, in Saint Paul’s phrase, of “life-giving spirit.”

The New Testament gives witness not to resuscitation or a return to the life of this world, but to a newness, a perfection. And it announces the good news that this world was, is, and will be blessed and perfected, beyond our wildest hopes, our grandest visions, by the love of God made present in Jesus. The New Testament also gives witness to the passage of Jesus from a limited, earthly mode of existence to a freed and eternal one. And it is Jesus’s promise that the same extraordinary thing will happen to us because of his redemptive sacrifice on the Cross.

A hallucination or a hoax cannot be reconciled with the dramatic and historically remarkable movement that, within twenty-five years after Jesus’s execution, and under the most agonizing conditions, created Christian communities across the Mediterranean world.

If some factual and astonishing experience was not at the foundation of the Christian movement, then what accounted for the improbable beginning, the rapid and surprising expansion, and the distinctive writings that reflect its origins?

If the success of Christianity depended solely upon the gifts and holiness of its leaders, it would long ago have disappeared along with so many other human projects. Instead, Christianity has continued to flourish because of the redemption and sanctification we celebrate at Easter.

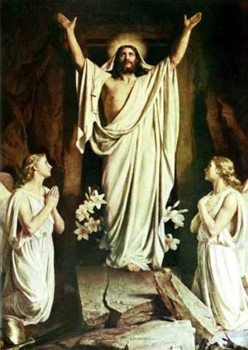

|

The Resurrection (Altarpiece) by Carl Bloch (1881). |

After developing his theory of relativity, Albert Einstein summed it up by saying the past, the present, and the future are in many ways an illusion. The genius of Christianity’s liturgical calendar is that it has always recognized this. When we say Christ has died, Christ is risen, Christ will come again, we are essentially talking about now, this instant: Christ is dying right now, Christ is risen right now, and Christ is among us again, here and now. This present moment is also our Easter morning, the first moment of the Resurrection of Jesus, for there is no passage of time in the realm of God.

The Jesus whom faith proclaims as the Lord of the universe is no longer defined and limited by time and space, as he was during his life in the flesh. He is, however, accessible to human beings who are defined by time and space. He is both historical man and transcendent God.

The Resurrection of Jesus is the central fact of Christian faith and life; it is not a wish, a pleasant fancy, or even something of the past. It is now.

“Jesus is risen from the dead” means that he has accomplished what would seem to be impossible and has entered into a new and permanent manner of existence — immortal, deathless, unlimited by any of our categories.

And now all creation is in the process of reaching in and through the Risen Jesus toward that final state in which God triumphs.

The Easter message, Dietrich Bonhoeffer wrote, is that “God is Death’s death.”

Earlier the English poet and cleric John Donne wrote in one of his Holy Sonnets:

“Death, be not proud,

though some have called thee

mighty and dreadful,

for thou art not so;

for those, whom thou think'st

thou dost overthrow,

die not, poor Death,

nor yet canst thou kill me.”

Reverend John Donne concludes his sonnet with this stirring Easter message: “One short sleep past, we wake eternally, and Death shall be no more; death, thou shalt die.”

And so we rejoice this morning as we remember Christ’s resurrection, for it was his promise to us that we, too, would rise again.

Jesus Christ is the death of Death.

Death, thou shalt die.

Image credits: (1) Caravaggio; (2) Francesca Buoneri; and (3) Carl Bloch.