The Stoning of Stephen:

What's So Special About The First Christian Martyr?

For Sunday May 18, 2014

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year A)

Acts 7:55–60

Psalm 31:1–5, 15–16

1 Peter 2:2–10

John 14:1–14

Back in 1987 I taught for three weeks at the Bangui Evangelical School of Theology in the Central African Republic. The seminary was founded in 1973 to train pastors from over twenty Francophone countries at a graduate level. Bangui holds a place in my heart because it was my first of six trips to Africa.

Today the seminary is closed. The campus has become a shelter for about 1500 refugees. The country is forgotten to the world. On the Human Development Index, the C.A.R. ranks 179th out of those 187 countries with data.

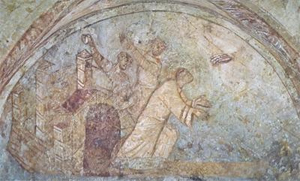

|

9th. century fresco, Chapelle Saint-Etienne, Abbey Church of Saint-Germain, Auxerre. |

Ban Ki-moon described the C.A.R. as in "free fall." Government doesn't exist. Civil servants don't go to their offices, taxes aren't collected, and the schools are closed. There's no budget, no army, no police force, no Parliament, no judges or jails. Over a million people — a quarter of the population, have fled their homes. France and the UN have warned of genocide.

One glimmer of hope is that last January Catherine Samba-Panza was elected as the interim president. “Everything we have been through has been the fault of men,” said Marie-Louise Yakemba, who heads a civil-society organization that brings together people of different faiths. "We think that with a woman, there is at least a ray of hope."

This week's reading from Acts 7:55–60 describes the stoning of Stephen. It's a story of mob violence and religious rage that signaled "a great persecution against the church at Jerusalem." We remember Stephen as the first of countless millions of Christian martyrs.

11th. century Byzantine icon. |

Just a few pages later, in Acts 12, king Herod executes James. Peter and Paul were martyred in Rome. Or consider Hebrews 10:33–34: “You stood your ground in a great contest in the face of suffering. Sometimes you were publicly exposed to insult and persecution; at other times you stood side by side with those who were so treated. You sympathized with those in prison and joyfully accepted the confiscation of your property.”

So began three centuries of persecution. At first they were sporadic and local, as with Nero. Decius made persecution a state policy. Diocletian unleashed the most severe government terror in March 303: “It was enacted that the meetings of the Christians should be abolished, churches be razed to the ground, that the Scriptures be destroyed by fire, that those holding office be deposed and they of their household deprived of freedom, if they persisted in their profession of Christianity.”

Christian martyrs make for a long list down through the centuries. We rightly honor them.

The French Revolution "dechristianized" France. The Soviet communists closed 98% of the Orthodox churches, 1,000 monasteries, and 60 seminaries. Between 1917 and the start of World War II, 50,000 Orthodox priests were martyred. Communists in China, Cambodia, North Korea, and Cuba have eradicated tens of millions of Christians.

|

Ivory carving, c. 1100. |

So, we remember Stephen as the first Christian martyr. But what does his story mean for us today? The Greek word "martyr" means "witness," but to what did Stephen bear witness? His death was gruesome and unjust, but no more so than many millions of others.

Christians can't claim any special persecution status. Other religions have experienced similar martyrdoms — indeed, sometimes at the hands of Christians.

Millions more have been martyred for reasons other than religion — for their ethnicity (Jews, Armenians, Tutsis), for economic ideology (farmers, land holders), social prejudice (intellectuals, artists), race (American blacks), and gender (women around the world like the inspirational Malala Yousafzai of Pakistan).

Christians are just one group among many that honors their martyrs. Very few times, places or peoples have been spared mass murder.

If you can bear to read it, I recommend the book by Daniel Jonah Goldhagen, Worse Than War; Genocide, Eliminationism, and the Ongoing Assault on Humanity (2009). Goldhagen estimates that between 127–175 million people were "eliminated" in the last century.

|

English Altarpiece by Michael Pacher, 1470. |

These people came from all regions of the world, and from all social, economic and political groups. The vast majority of these victims were killed in their own countries, by their fellow citizens, by willing and non-coerced murderers, and almost never with any substantial dissent. Eliminationism is thus "worse than war."

The numbers are mind-numbing, and therein lies our challenge. They bring to mind the infamous remark by Stalin in 1947 about the famine in the Ukraine that was killing millions: “If only one man dies of hunger, that is a tragedy. If millions die, that’s only statistics.”

The martyrdom of Stephen recalls this epigram of Stalin.

In fact, Stephen isn't the first Christian martyr. Every year after Christmas, the church pivots sharply from joy and celebration to a most unlikely feast day — Herod's "slaughter of the innocents." Christians honor the children of Bethlehem as the first martyrs of the gospel. By the late fifth century the "slaughter of the innocents" had become the subject of church liturgy, art, and literature.

Like the babies of Bethlehem, the martyrdom of Stephen disabuses us of a sentimental gospel. It roots us in the real world of industrial scale slaughter. The one man Stephen helps us to remember the individual humanity of the millions of people we might otherwise forget — like those in the C.A.R.

|

Welsh Stained glass window, 1822, Church of St. Stephen, Old Radnor, Powys. |

In her acceptance speech after her election, Samba-Panza urged all sides to stop the slaughter. She then said, "starting today, I am the president of all Central Africans, without exclusion."

With Stephen we don't invoke any Christian privilege. Stephen expands our vision instead of narrowing it. We choose not to forget or exclude anyone. We honor the life of every person in all the world, for God created each one of us in his image.

In the language of our Jewish forbears, we "speak up for those who have no voice, for the justice of all who are dispossessed. Speak up, judge righteously, and defend the cause of the oppressed and needy." (Proverbs 31:8–9).

NOTES:

On Bangui and the C.A.R., see the article by Adam Nossiter.

On the Stalin quote, see here.

Image credits: (1) Flickr.com; (2) Wikipedia.org; (3) Wikipedia.org; (4) Wikipedia.org; and (5) Stained Glass in Wales.