God's Mercy On Us All

For Sunday August 17, 2014

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year A)

Genesis 45:1–15 or Isaiah 56:1, 6–8

Psalm 133 or Psalm 67

Romans 11:1–2a, 29–32

Matthew 15:10–20, 21–28

Last Saturday, JwJ held its quarterly board meeting to review the end of our fiscal year on June 30. Our board gathers several times a year, but this meeting was special. Having launched JwJ in the summer of 2004, it marked the end of ten years for our "weekly webzine for the global church." And in ways I never could have imagined back in 2004, the operative word here is "global."

I reported to the board that JwJ has served over 4 million readers in our ten years — about 1,000 readers a day. Compared to the heavy hitters on the internet, that's small beer.

But what especially interests me, and is so gratifying, is that our readers come from 236 countries and territories. There are only two countries in the world where we've never had any readers — North Korea and Western Sahara. Each and every week, readers from 100 countries visit JwJ.

Our readership reminds me of the global character of God's kingdom.

|

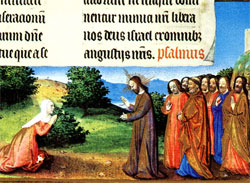

Canaanite woman kneeling before Jesus. |

The first pages of the Bible describe a good creation gone very bad. The ground is cursed. Cain kills his brother Abel, and so begins fratricide. Humanity is badly divided by a "babel" of confused languages. We've been living this dark history since the dawn of civilization.

But that's only the beginning of our human story, not its end. God intends something far better for us. The last pages of the Bible describe a city with people from "every nation, tribe, people, and language." A divided humanity is thus united. The divine embrace has conquered human exclusion. Instead of sickness and violence, there's a tree whose leaves are for "the healing of the nations."

Four thousand years ago, in the most important pivot point in the Bible (Genesis 12:1), an obscure nomad named Abraham heard the promise of God. God promised Abraham that in him "all the families of the earth will be blessed" (Genesis 12:3). God repeated this promise to Abraham's son, Isaac, and to his grandson, Jacob.

Through Abraham, God formed one special people, Israel. And in electing the one nation Israel, God has always intended to bless every nation.

Fast forward two thousand years from the time of Abraham. After his resurrection, Jesus told his followers to spread his message "to all nations, beginning at Jerusalem." In his parallel passage, Mark renders the meaning more emphatic by writing "all creation." Similarly, in Luke's sequel to his gospel, Jesus told his timid followers, "you will be my witnesses in Jerusalem, and in all Judea and Samaria, and to the ends of the earth."

Fast forward another two thousand years to today. God's promise to Abraham and its fulfillment in Jesus have become an empirical reality. The book of Acts begins in Jerusalem, proceeds geographically outward, and ends with Paul imprisoned in Rome. His last recorded prayer before martyrdom was for "all nations" (Romans 16:26).

But that was only a modest beginning. Starting with a few uneducated, bedraggled disciples, today about a third of the world identifies itself as Christian, nearly twice as many as those who follow Islam or Hinduism (roughly one billion each).

The particular story of the one man Jesus includes a universal welcome to every person of every time and place. Jesus unites what divides us. In him our many causes of exclusion become opportunities for embrace. Jesus, himself a man on the margins of society, brings the outsider inside. "No outcasts were cast out far enough in Jesus's world to make him shun them" (Wills).

The readings this week show how this is true in the areas of sexuality and nationality.

Ancient Israel excluded eunuchs from its community as "blemished" people: "No one who has been emasculated by crushing or cutting may enter the assembly of the Lord" (Deut. 23:1). People with "damaged testicles" (Levit. 21:20) were only one of many groups of people who were stigmatized as disfigured and defective, and so excluded by the community.

Whether by birth or by castration, eunuchs could not reproduce. They were biologically inferior and therefore liturgically excluded. Eunuchs were deformed and incomplete human beings. Castrating your enemy was a way to humiliate him even after death (1 Samuel 18:27). Eunuchs were at best "safe" and harmless people who could serve in a king's court.

|

Jesus grants the wish of the Canaanite woman. |

Isaiah 56 describes how God reverses this exclusion: "Let not any eunuch complain, 'I am only a dry tree.' To the eunuchs who keep my Sabbaths, who choose what pleases me and hold fast to my covenant — to them I will give within my temple and its walls a memorial and a name that will not be cut off."

The play on words is shocking: your genitals might be cut off, but your name will not be cut off from God. Instead of being rejected from the temple, eunuchs will be remembered in the temple.

Jesus goes beyond eunuchs who were "born that way or made that way by men." He honors those who've made themselves eunuchs for the kingdom of God (Matthew 19:12). The brilliant scholar Origen (185–254) is perhaps the best example in the early church of taking Matthew 19:12 literally. And in Acts 8 Luke portrays the Ethiopian eunuch as a paradigm of vibrant faith rather than of liturgical exclusion.

So, that which was a source of humiliation and exclusion, a sexual "deformity," has in God's economy become a sign of divine acceptance.

Psalm 67 does for nationality what Isaiah does for sexuality; it expands the boundaries of God's embrace to include people who were vilified as enemies and outsiders.

I'm always amazed at how some of the psalms move beyond the parochial to the global. The ancient poet comes from a geo-politically marginal people, yet he prays for God's blessings to fall on "all nations." God is not a territorial god, he says; he's the lord of all nations and peoples. He invites "all the ends of the earth" to offer praise and thanks.

Jesus reinforces this point in this week's gospel. A Canaanite woman who knew that in the eyes of the Jews she was a despised "dog" nevertheless earned praise as a woman of great faith (Matthew 15:28).

It's a short step from the categories of sexuality and nationality to economics, politics, gender, and socio-economic class. "In Christ," writes Paul, "there is neither Jew nor Greek, slave nor free, male nor female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus."

Christians are thus radical egalitarians when it comes to the love of God. We are all equidistant from the heart of God.

In the epistle for this week, Paul levels the playing field. He says that we're all in the same boat. "God has bound all people over to disobedience so that he might have mercy on them all" (11:32).

Image credits: (1) Christusrex.org and (2) Christuxrex.org.