Jesus: "The Irresistible Incomprehensible"

For Sunday August 24, 2014

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year A)

Exodus 1:8–2:10 or Isaiah 51:1–6

Psalm 124 or Psalm 138

Romans 12:1–8

Matthew 16:13–20

This summer I read the novel Americanah by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. The New York Times named it one of the top ten books of 2013. Adichie is routinely mentioned as one of Africa's most important contemporary writers. Her work has been translated into thirty languages.

Americanah is a story about how race and place shape our personal identity and sense of belonging. Ifemelu, the protagonist and narrator, never thought of herself as black until she moved from Nigeria to America. The color of her skin and the texture of her hair were only two aspects of her personal identity that assumed new meaning in a new place. There was also language.

|

Head of Christ by Warner Sallman (1940). |

Whenever her Aunty Uju spoke to white Americans in the presence of white Americans, she spoke with an American accent. But that artifice came with a cost — there "emerged a new persona." Ifemelu felt like America had "subdued" her Aunty Uju, and she vowed that wouldn't happen to her. She even remembers the exact day when she stopped speaking with an American accent and reverted to the natural lilt of her Nigerian language.

Immigration intensifies Ifemelu's search for her true self, for living in a new place is often a time when we reinvent ourselves, willingly or not, knowingly or not, into new versions of our old selves. She leaves her Nigerian boyfriend and falls in love with both black and white American men. She observes differences between African Americans and American Africans.

Wherever she turned, Ifemelu encountered "slippery layers of meaning that eluded her" — music, food, church, school, and work. Even the bearing and demeanor of her cousin revealed "that fine-grained mark that culture stamps on people."

Returning to Nigeria thirteen years later was just as difficult: "She was no longer sure what was new in Lagos and what was new in herself." At a meeting of Nigerian "returnees" from the west, she feared that she had become the smug cosmopolitan "Americanah" that she had vowed never to become. Still, she couldn't help but see Nigeria through American eyes. Her identity had been shaped by race, place, and a host of other powerful forces.

The gospel this week is about the personal identity of Jesus. One day he asked his disciples, "Who do people say that I am?'

It's instructive that this question was raised, and that it survives in our historical records. It indicates that the earliest memories of the earliest believers were agitated about the personal identity of Jesus. Exactly who was he? From then until now, the question has always elicited controversy rather than clarity.

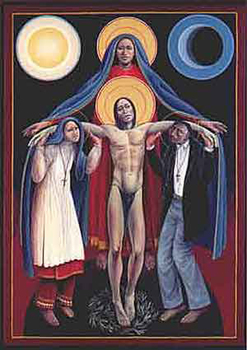

|

Black Joseph with the Young Jesusby Wiktor Szostalo. |

There were rumors of miracles, healings, and exorcisms. He itinerated from village to village with rich women who supported him. He forgave sins. His brothers didn't believe in him. Conscientious Jews were shocked that he violated purity laws, ate with sinners, and embraced Gentiles. Many of his closest supporters stopped following him. Others said that he told people not to pay their taxes.

And so Rome executed him as a criminal. Jesus was executed not as an innocent victim or because of a miscarriage of justice, says William Stringfellow. No, "Of the charges against him," — subverting the nation and undermining its very existence, Jesus was "guilty beyond any doubt."

Who was Jesus? Nobody could agree. "Some say John the Baptist, Elijah, Jeremiah, or one of the prophets."

Jesus then turns his theological question into a personal query. "What about you? Who do you say that I am?" And so my own identity is bound up with the identity of Jesus.

Peter, the early confessor and later denier, responded, "Thou art the Christ, the son of the living God."

This description of Jesus as the son of God recurs throughout the gospels: at Gabriel's annunciation to Mary, at his baptism, his transfiguration, with adoration by his disciples and mockery by his enemies at his crucifixion. Jesus himself claimed a unique filial relationship with God, whom he called "Abba." John says that he wrote his gospel "so that you may believe that Jesus is the Messiah, the Son of God."

In his book What Jesus Meant (2006), the historian Garry Wills writes, "He intended to reveal the Father to us, and to show that he is the only-begotten Son of that Father. What he signified is always more challenging than we expect, more outrageous, more egregious."

Even if we identified the original "Jesus of history" behind the later "Christ of faith," he would become more rather than less mysterious to us.

|

Native American Christ. |

And so, concludes Wills, "tremendous ingenuity has been expended to compromise these uncompromising words. Jesus is too much for us."

In Reading Jesus (2009), Mary Gordon describes how a few years ago she was stuck in a taxi in New York City. When the driver turned on the radio, she was forced to listen to some Christian program. Gordon, the Millicent C. McIntosh Professor in English and Writing at Barnard College, has written fifteen novels, memoirs, and works of literary criticism. Raised as a Catholic, she was vaguely familiar with the Scriptures.

But listening to the radio that day provoked a realization that filled her with "a clutch of anxiety and shame." She was almost sixty but had never read the four gospels straight through from the beginning of Matthew to the end of John. Her book describes that "disturbing and exhilarating enterprise."

Gordon doesn't settle for a superficial reading: "It seemed to me that if I were going to take this project seriously, I would have to question my own reading, and examine its lacunae: I would have to ask myself, do I really know what the Gospels are about, or have I invented a Jesus to fulfill my own wishes?" Her book thus aims "for a tone that is personal and self-questioning."

She first explores what draws her to Jesus as the "irresistible incomprehensible." Beginning with the prodigal son, she wonders about God's "economy of mercy" that invites celebration, joy, and generosity, but that also questions us, "are you envious because I am generous?"

And so "the radical challenge of Jesus: perhaps everything we think in order to know ourselves as comfortable citizens of a predictable world is wrong."

The second half of her book explores problem texts, "for there are as many reasons for being appalled by Jesus as there are for being drawn to him." She admits that it's tempting to excise from the Bible the parts that you don't like, but she's far too honest to take the easy way out.

Miracles are a problem for post-Enlightenment moderns dedicated to the scientific method, but in the end she would not delete them. Calls to asceticism and self-denial make her wonder about happiness and pleasure. The call to "be perfect" sounds ideal but it's impossible. Apocalyptic language is violent, and encourages readers to see themselves as elect and their enemies as damned. The anti-Semitism of John and the divinity of Jesus complete her survey of problem texts.

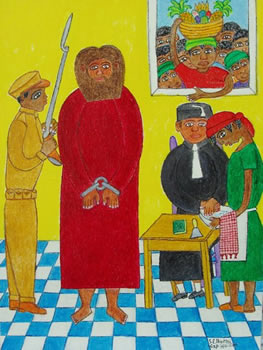

|

Jesus before Pilate, Seymour E. Bottex, Haiti. |

In a final chapter Gordon contemplates the seven last words of Christ. "What words could be plainer than these? The plainness of the language gives me the courage for a plain assertion, an assertion that I find embarrassing to make. But embarrassment is not one of the great emotions, and these words demand the attempt at a response that does not mire itself in self-regard. So now I say: these words are the foundation and basis of my religious life. They serve for me as a filter, or a funnel, in which everything that has gone before in the Gospels pours itself, and arrives at the end as a pure tincture: clear, usable, entirely free of sediment and residue. The living water. The water of life."

These are not the last words of Oedipus, Lear, or Alexander the Great, says Gordon. "They are the seven last words of Jesus." And so she concludes, his life and death either "have no meaning or create a meaning unique in the history of the world."

For further reflection:

Marcus Borg, Jesus; Uncovering the Life, Teachings, and Relevance of a Religious Revolutionary (San Francisco: Harper, 2006), 343pp.

Marcus Borg and John Dominic Crossan, The Last Week; A Day-by-Day Account of Jesus's Final Week in Jerusalem (San Francisco: Harper, 2006), 220pp.

Margaret Bullitt-Jonas, Christ's Passion, Our Passions; Reflections on the Seven Last Words from the Cross (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Cowley Publications, 2002), 92pp.

Harvey Cox, When Jesus Came to Harvard; Making Moral Choices Today (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2004), 338pp.

Richard Wightman Fox, Jesus in America: Personal Savior, Cultural Hero, National Obsession (San Francisco: Harper, 2004), 528pp.

Mary Gordon, Reading Jesus; A Writer's Encounter with the Gospels (New York: Pantheon Books, 2009), 205pp.

Andrew Greeley, Jesus; A Meditation on His Stories and His Relationships with Women (New York: A Tom Doherty Associates Book, 2007), 172pp.

Stanley Hauerwas, Cross-Shattered Christ; Meditations on the Seven Last Words (Grand Rapids: Brazos, 2004), 108pp.

Paul Johnson, Jesus: A Biography from a Believer (New York: Viking, 2010), 242pp.

Stephen Prothero, American Jesus: How the Son of God Became a National Icon (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2003), 376pp.

Joseph Ratzinger, Pope Benedict XVI, Jesus of Nazareth (New York: Doubleday, 2007), 374pp.

Garry Wills, What Jesus Meant (New York: Viking, 2006), 144pp.

Image credits: (1) Beliefnet.com; (2) Szostalosculpture.com; (3) www.actd.ca; and (4) Trocadero.com.