The Outsider Prophet

By Debie Thomas

For Sunday January 18, 2015

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year B)

1 Samuel 3:1-20

Psalm 139 1-6, 13-18

1 Corinthians 6:11-20

John 1:43-51

The story of the prophet Samuel's call in the temple of Shiloh is a Sunday School teacher's dream. It's dramatic and suspenseful, it has a pleasing narrative arc, and it's blessedly brief. (Always a plus with the under-ten set.). More importantly, it's one of only a handful of Bible stories in which a child plays the starring role.

I heard the story fairly often when I was growing up. I also heard the lessons I was supposed to absorb from it, lessons about going to church (Samuel heard God's voice in the temple), obeying my elders (Samuel did exactly as Eli instructed), and opening my heart to God (Samuel invited God to speak to him).

But when I was a kid, those lessons didn't quite take; I was too spooked by the possibility that Samuel's story could happen to me. I knew I was supposed to feel excited at the prospect of a call from heaven. I knew the story meant that even the youngest of us have roles to play in his kingdom. I even knew what I was supposed to say if my moment in the noctural spotlight ever came: "Speak, Lord, for your servant is listening."

|

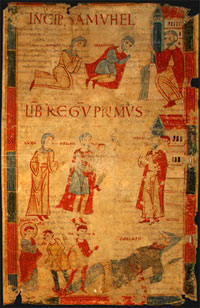

Four Scenes from the First Book

of Samuel, late 11th century, miniature on vellum. |

But I also knew myself. I was a high-strung kid with a radar for creepy things, and I actively feared the night. I knew that if I heard a strange voice calling my name in the darkness, I wouldn't be able to speak a word for terror. I would bolt out of bed, run to my parents' room, crawl into bed between them, and refuse to budge till morning.

These days, if I hear a voice in the night, I probably won't call up my parents. But I will question my sanity. Or cut back on caffeine. Or sign up for yoga. I'll probably do everything but believe that God is talking to me. If my childhood issue with Samuel's story was that it felt too real for comfort, my issue now is that feels too un-real. Impossible to integrate into the world I live in.

"The word of the Lord was rare in those days; visions were not widespread," the writer of 1st Samuel says by way of a preface. Sound familiar? As Christians, we profess belief in a God who longs to speak to his children. Abandoning us to silence is presumably not what God desires to do. But as modern, scientifically-inclined people, we don't sit easily with voices and prophetic callings. What would it take in our skeptical age to once again welcome the voice of God? What would it look like to retrain our secularized imaginations? To honor what we know of human psychology and suggestibility, and still hear the sacred when it breaks into our lives?

|

God calls Samuel, anonymous, Utrecht, c. 1430. |

These are huge questions, and I don't claim to know the answers. But Samuel's story does point me in a direction I find intriguing — a direction somewhat different from the one I heard in Sunday School.

As the story begins, Samuel is "ministering to the Lord under Eli." In a vivid sermon on this Old Testament passage, Barbara Brown Taylor describes what the boy prophet's life in the temple might have looked like:

"We can only guess what it was like for Samuel as the faithful brought their burnt-offerings, their sin-offerings, and their guilt-offerings to the temple. They were burdened, ashen-faced people, most of them, hauling their stubborn animals up to the altar to be killed. There was a great deal of blood, blood splashed on the altar and blood sprinkled on the veil that separated the Holy of Holies from the rest of the sanctuary. The burning incense did battle with the smell but could not beat it; the place stank, no getting around it. Maybe Samuel tended the cauldron where the sacrificial meat was boiled, or helped Eli locate the portion he was allowed to eat as the temple priest. Maybe Samuel was allowed to feed on some of the scraps himself; there was little else for a growing boy to eat."

"At night he lay down by the ark of God, the legendary throne of the invisible king Yahweh that Israel carried into battle at the head of her armies. It was reputed to contain all the sacred relics of the nation's past: a container of manna, Aaron's budded rod, the tablets of the covenant. Sleeping next to it had to be like sleeping in a graveyard, or under a volcano."

|

God calls Samuel, French, c. 1250. |

Not, in other words, a day — or a boyhood — spent in the park. But a boyhood spent in close proximity to all that was considered sacred in his day. A boyhood spent in the very household of God.

Having grown up a pastor's daughter, always in and around the church, I can't help but relate in a tiny way to this aspect of Samuel's life. Over the years of his apprenticeship, he would have enjoyed an insider's view of religious life. The language of faith would have been his first language — the language he spoke most fluently. He would have handled holy objects, listened to whispered prayers, and witnessed moving conversions. Granted, he would also have seen the contradictions, the intrigues, the scandals. But his circumstances would have primed him to know God early and well.

Or so I'd like to assume. What the story reveals, however, is a surprise: "Samuel did not yet know the Lord, and the word of the Lord had not yet been revealed to him."

The easy interpretative move to make here is to say that there's a big difference between knowing about God, and knowing God. Which is true. But I wonder if the writer of 1st Samuel is also saying something bolder. Something about the spiritual risk involved in becoming too insular, too "churchy." Something about the shadow side of human institutions — even the most well-meaning and well-run religious ones. Something about the necessary role of the outsider-as-prophet.

When I think about my own God-saturated upbringing, I am filled with gratitude. I'm so glad I had the privilege to grew up in the Church. To be shaped from earliest memory by its rituals and rhythms. But Samuel's story gives me pause. Is it possible that my over-familiarity has made it harder for me to hear new and unexpected words from God? Is it possible that my churchiness dulls my ears to his call?

|

Samuel anoints Saul as King, Maciejowski Bible (13th century illuminated manuscript). |

If so, I take comfort in the fact that God didn't give up on Samuel. He called, called, and called again. He called until Samuel learned how to listen.

According to the religious hierarchies of the day, the people who should have heard God's voice in this story were Eli and his sons. They were the authorities, the ultimate insiders by birth and by vocation. But they were not the ones God chose.

Instead, God chose Samuel. A child. A boy on the periphery, one whose capacity for openness and wonder was dulled, perhaps, but still recoverable. A child who wasn't bound by the political interests of his elders. A child who could tolerate an unfamiliar voice and an uncomfortable message — a message that would upend the very institution he knew best.

This week, people around the world honor the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., America's great Civil Rights leader and prophet. King was an outsider, perfectly positioned to speak truth to power. Like Samuel, King was willing to make his listeners uncomfortable — even at great cost to himself.Image credits: 1) National Gallery of Art; (2) Biblical Art on the WWW; (3) Biblical Art on the WWW; and (4) www.medievaltymes.com.