The True End of True Prayer:

What I Pray and Why

By Dan Clendenin

For Sunday February 8, 2015

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year B)

Isaiah 40:21–31

Psalm 147:1–11, 20c

1 Corinthians 9:16–23

Mark 1:29–39

One of my earliest memories is of my mother putting me to bed at night in my down stairs bedroom, then praying while she scratched my back. My mother had six children by the time she was thirty-six, and there she was, doing the bed time ritual with her youngest: "Now I lay me down to sleep." In a ploy for more back scratching, I might advance to the Lord's Prayer. For that "adult" prayer I aimed for a greater gravitas with my little voice.

There are critical questions and spiritual conundrums concerning prayer. They are important and deserve our attention. Nonetheless, I still pray. Although I sometimes find it hard to pray, I generally find it impossible not to pray. Maybe I pray because of my mother's love, or because it's the "right" thing for a Christian to do.

I also pray because Jesus prayed.

I go to bed early and get up early, so I resonate with Mark's gospel: "Very early in the morning, while it was still dark, Jesus got up, left the house and went off to a solitary place, where he prayed." Luke includes this memory about Jesus, and adds several others.

Luke describes how "Jesus often withdrew to lonely places and prayed," and that one time he "went out into the hills to pray, and spent the night praying to God."

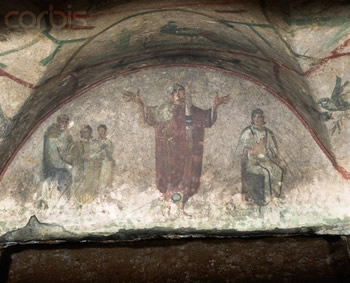

|

Catacomb fresco of a family praying. |

Jesus prayed for Peter "that your faith might not fail." He taught the disciples the "Lord's Prayer." One of his parables taught us "always to pray and never give up." In the last hours of his life he prayed a great Unanswered Prayer — "Let this cup pass from me," an excruciating Prayer of Dereliction — "My God, why have you forsaken me?" and a prayer for his executioners — "Father, forgive them."

In my morning darkness the house is quiet. I can hear the clock ticking and the furnace blowing. My neighbor starts his car at the same time every morning and leaves for work. The garbage trucks at the restaurant next door empty the dumpsters. At some point our golden retriever starts to whimper, a signal that prayer is over and the day begins.

My prayers are standard issue. I pray for family and friends, commending them to what Gerard Manley Hopkins called God's "far finer and fonder care." I try to remember people with special needs. I pray for what Isaiah called God's "awesome deeds we did not expect."

I also try to imitate the early desert monastics.

In the Sayings of the Desert Fathers, there's a story about Macarius the Great (born c. 300), a former camel driver. One day someone asked him how to pray. "There is no need at all to make long discourses," he advised. "It is enough to stretch out one's hands and say, 'Lord, as you will, and as you know, have mercy.' And if the conflict grows fiercer say, 'Lord, help!' He knows very well what we need and he shows us his mercy."

In his book Chapters on Prayer, Evagrius of Ponticus (345–399) offers this advice: "Pray not to this end, that your own desires be fulfilled. You can be sure they do not fully accord with the will of God. Once you have learned to accept this point, pray instead that 'thy will be done' in me. In every matter ask him in this way for what is good and for what confers profit on your soul, for you yourself do not seek this so completely as he does."

When I'm really on my game, I aim for two things in prayer — candor and confidence.

First, I try to be honest before God. It's not easy. Moving beyond pious platitudes, spiritual cliches, and tired habits is hard. So, I keep returning to that marvelous prayer that begins so many Anglican services, that before God all my thoughts are known and none of my secrets are hid. I might as well try to be honest.

This might sound like the worst sort of exposure, but it's really an embrace. I can be my true and unadorned self before God, no editing required.

This is why the Psalms are so instructive. All those prayers of discouragement and despair. Prayers about unanswered prayers. Questions about God's silence and absence. Prayers of imprecation against your enemies. Prayers of presumption that God is for Us and against Them. Prayers of manic praise, prayers of wonder and gratitude. In short, prayers that run the gamut of human emotions.

For some contemporary prayers of brutal honesty, I recommend the book Idiot Psalms (2014) by the poet Scott Cairns.

I pray with Peter, "Lord, I'm a sinful man." I pray with Paul, who admitted that we don't know how to pray. I pray with Isaiah, "Woe is me, I am a man of unclean lips." I pray with the publican, "Lord have mercy on me, a sinner." And I definitely pray with the Gerasene demoniac: "My name is legion" — all those voices in my head. Crazy dreams. The time I waste. My obsessions and compulsions, my fears and worries.

|

Early fresco of woman at prayer. |

In prayer we seek what John Cassian (360–430) called "integrity of heart" or "integral wholeness." But when you're honest before God, that can feel far off.

Here's Cassian's self-diagnosis in his Institutes and Conferences — lethargy, sleeplessness, unsettling dreams, impulsive urges, self-justification, seething emotions, sexual fantasies, pious pretense that masked as virtue, self-deception, clerical ambition and the desire to dominate, crushing despair, confusion, wild mood swings, flattery, and the dreaded "noonday demon" of acedia ("a wearied or anxious heart" that suggests close parallels to clinical depression).

Cassian further admits that "there are many things that lie hidden in my conscience which are known and manifest to God, even though they may be unknown and obscure to me." And this is a monk who had devoted his entire life to prayer!

So, when I pray, I aim for candor. I try to keep it real. To be honest with myself and before God. To confess our Sunday eucharistic prayer that "we break this bread for our own brokenness."

This isn't self-hatred or self-help. It's just acknowledging part of what it means to be human. Best of all, in a wonderfully felicitous phrase, Cassian says we admit our brokenness "without any obfuscating embarrassment."

When I pray I also try to be confident — that is, to remember that I'm loved.

1 John 3 reminds us: "See what great love the Father has lavished on us, that we should be called children of God! And that is what we are!" Paul says that "nothing can separate us from God's love."

For those of us who like to earn our way, or prove ourselves to God, ourselves, and to others, it's hard to do nothing at all but accept God's love. Edwina Gateley's beautiful poem is full of wise advice:

Be silent.

Be still.

Alone.

Empty

Before your God.

Say nothing.

Ask nothing.

Be silent.

Be still.

Let your God look upon you.

That is all.

God knows.

God understands.

God loves you

With an enormous love,

And only wants

To look upon you

With that love.

Quiet.

Still.

Be.Let your God—

Love you.

Yes, God is infinite and Wholly Other, and therein lie the mysteries of prayer. But in his own prayers Jesus reminds us that God is also intimate, like a Loving Father.

To experience God's love is the true end of all true prayer.

Paul prays for the Ephesians that, "being rooted and established in love, you may have power, together with all the Lord’s holy people, to grasp how wide and long and high and deep is the love of Christ, and to know this love that surpasses knowledge — that you may be filled to the measure of all the fullness of God."

And so, says the English mystic Juliana of Norwich (1342–1416), "the greatest honor we can give Almighty God is to live gladly because of the knowledge of his love."

Image credits: (1) Wikimedia.org and (2) CorbisImages.com.