When Less Is More

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year B)

For Sunday March 15, 2015

Fourth Sunday in Lent

Numbers 21:4–9

Psalm 107:1–3, 17–22

Ephesians 2:1–10

John 3:14–21

My Lenten disciplines are typically pretty standard fare. Last year I read through the four gospels. I've given up coffee and alcohol — and discovered that abstinence is easier than self-control.

Another time I ate just one meal a day in an attempt to identify with those billions of people who go hungry every day. Eating once a day was hard. By late afternoon I felt cold, even if I put on a sweater. I felt agitated as well, unable to concentrate on anything. My fast also led to legalistic hair-splitting — wasn't an afternoon snack the same as an early pre-dinner appetizer? And didn't gorging myself during my one meal defeat the purpose of fasting in the first place?

|

Moses and the Brazen Serpent, Belgium, c. 1160 (copper alloy, gold, enamel engraving). |

I think these disciplines were good for me, even though I struggled with my motives. Lenten practices of sacrifice and discipline serve a positive purpose in our culture of indulgence and entitlement.

Lenten disciplines also appeal to my ascetic streak. My wife complains that I'm an "all or nothing" sort of person who won't take an afternoon hike but will do a 500-mile pilgrimage. I remember right where I was sitting at the dinner table thirty years ago when a friend joked, "Dan, were you born serious?"

The early desert monastics warned of extremist zeal. They knew from their own experiences that there's a thin line between self-discipline and self-justification. In our culture of merit, I find that Lenten disciplines can become a way to prove myself, spiritually-speaking — to others, to myself, and certainly to God.

But trying to earn God's love is a fool's errand. It isn't necessary or even possible.

So, for Lent this year I'm trying something different. I'm doing nothing at all. I'm trying to follow Edwina Gateley's wisdom to be quiet and still before God. To say nothing. Ask nothing. And do nothing. Nothing, that is, except to "let your God / Look upon you with his enormous love. / That is all."

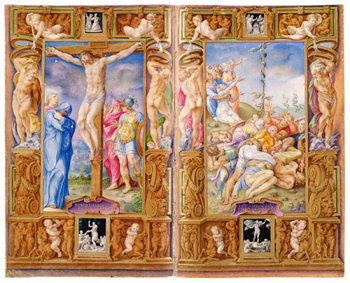

|

The crucifixion, Moses and the brazen serpent, illuminated mss. by Giulio Clovio, 1546. |

And that's hard in a whole different way.

I get support for my discipline-free Lent from my wife. She likes to joke that "Lent isn't in the Bible." She's on the right side of Scripture, but the wrong side of church history — since the fourth century, Christians have observed the 40 week days before Easter as a season of reflection, repentance, fasting, and acts of mercy. Nonetheless, she makes a good and very Protestant point.

A friend also encouraged me last week when he described how his spiritual director told him to abstain from all his tried-n-true ways of seeking God — conversational prayer, meditation, the rosary, "Christian" books, lectio divina, and the like. He's "fasting" from all that hard work he does to relate to God.

Our Jewish friends have an ancient ritual to address this problem of trying too hard. It's called Kol Nidre — in Aramaic, "all vows." The Kol Nidre is a declaration that is recited at the beginning of the service on the eve of Yom Kippur (Day of Atonement).

The cantor chants a prayer that begins with the first two words Kol Nidre:

|

Moses and the serpent, German stained glass, late 14th century. |

"All vows, obligations, oaths, and anathemas, whether called 'ḳonam,' 'ḳonas,' or by any other name, which we may vow, or swear, or pledge, or whereby we may be bound, from this Day of Atonement until the next (whose happy coming we await), we do repent. May they be deemed absolved, forgiven, annulled, and void, and made of no effect; they shall not bind us nor have power over us. The vows shall not be reckoned vows; the obligations shall not be obligatory; nor the oaths be oaths."

The idea behind Kol Nidre is that, however well-intended, we break our promises to God. So, I "repent" of my vows, and receive forgiveness for and freedom from them.

In John's gospel this week, Jesus describes our struggle between light and dark, life and death, salvation and condemnation, belief and unbelief. No one is immune from this struggle. Nobody gets a free pass. "All of us," says Paul in Ephesians, are implicated. And the struggle comes to us, he says, "by nature."

Indeed, "the basic and most fundamental problem of the spiritual life," said Thomas Merton, "is this acceptance of our hidden and dark self."

So, what am I to do? Double down on earnest religious effort?

|

Moses and the brazen serpent, Danish wall painting, c. 1520. |

John tells a story from Numbers 21 to point the way forward. Just as Moses lifted up a bronze serpent in the desert that healed people merely by looking at it, so today we only have to look to the love of God. There's nothing else we can or should do.

In his little epistle, John strips away all pious pretense with a shocking admission: "In this is love, not that we loved God, but that he loved us." The only thing I'm asked to do is "to know and rely upon the love that God has for us” (1 John 4:10, 16).

Paul says the same thing. I experience God's favor "by grace through faith," apart from any human merit. His goodness is a free gift, not a reward for my spiritual efforts. And my faith? Luther compared faith to "the beggar's empty hand" that receives a gift. God only asks me to accept his acceptance, in the words of the hymn, "just as I am, / without one plea."

This Lent I want to experience what Denise Levertov describes in her poem The Avowal.

As swimmers dare

to lie face to the sky

and water bears them,

as hawks rest upon air

and air sustains them,

so would I learn to attain

free fall, and float

into Creator Spirit’s deep embrace,

knowing no effort earns

that all-surrounding grace.

A true saint, said Merton, is not someone who has become good through strenuous disciplines, but someone who has experienced the free goodness of God.

For further reflection:

On Edwina Gateley's poem, see her book There Was No Path So I Trod One (2013).

Cf. Juliana of Norwich (1342–1416), from her Revelations of Divine Love.

The love of God most High for our soul

is so wonderful that it surpasses all

knowledge. No created being can fully know

the greatness, the sweetness, the

tenderness, of the love that our Maker has

for us. By his Grace and help therefore let

us in spirit stand in awe and gaze, eternally

marvelling at the supreme, surpassing,

single-minded, incalculable love that God,

Who is all goodness, has for us.

Image credits: (1) Victoria and Albert Museum (London); (2) The Morgan Library and Museum (New York, NY); (3) State Hermitage Museum (St. Petersburg, Russia); and (4) The-Orb.net.