It's my pleasure to welcome Erin McGraw back to JwJ for this conversation about art, faith, and the imagination. (You can read the 8th Day essays she's written for us here and here). Erin is the author of six books of fiction, most recently Better Food for a Better World: A Novel. Her short work has appeared in such magazines as The Atlantic Monthly, Good Housekeeping, The Southern Review, The Kenyon Review, STORY, and Image. A former Stegner Fellow at Stanford University, she has received fellowships from the Ohio Arts Council and the corporations of MacDowell and Yaddo. She is a professor emerita at the Ohio State University, and lives in Tennessee with her husband, the poet Andrew Hudgins.

Debie: Erin, welcome once again to JwJ. Thank you so much for joining us.

Erin: This is a complete pleasure. I'm delighted to be here.

I'd like to begin by asking you about the intersection of faith, art, and vocation in your own life. In an 8th Day essay you wrote for us last year, you described yourself as a "stealth Christian." You argued that artists are not the same thing as preachers. ("We who are not preachers are not called on to preach.") What do you feel called to as an artist of faith? How does your Christianity shape your vocation as a writer, and what role does "stealth" play in that vocation?

Can I answer that backwards? Whatever vocation I have insists that I not write stories of Christian uplift. I'm not interested in writing about how the faithful should behave in any situation, but I'm very interested indeed in writing about how believers, especially wobbly ones, often do behave when the heat gets turned up.

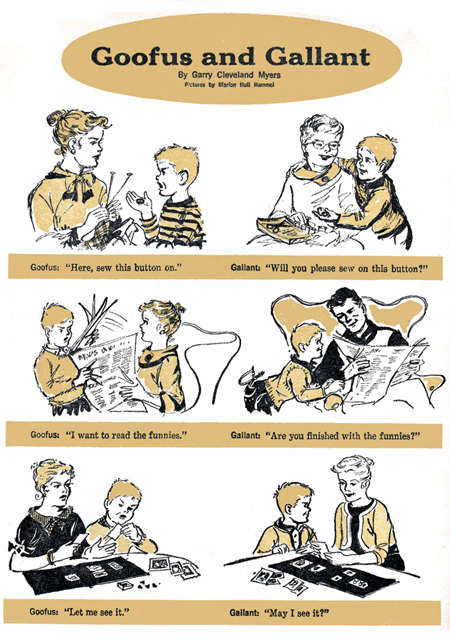

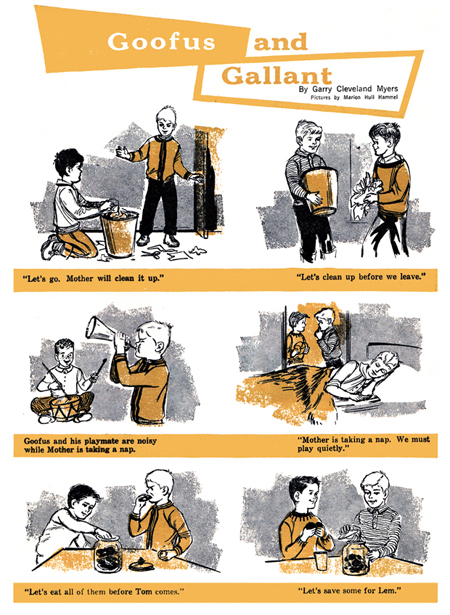

Good literature doesn't exist to provide moral exemplars. As any kid who read "Goofus and Gallant" in doctor's waiting rooms can tell you, perfectly upright people are dull, and they're mercifully rare in real life, which tells me we don't need to spend a lot of time thinking about them. Why else would we so commonly turn on the news to hear that yet another politician who presented herself as ethically unsmirched is revealed to be pretty darn smirched? I generally find those stories grimly entertaining; they certainly ratify my world view.

This isn't to say that I think good literature requires perpetually tawdry characters; good literature isn't automatically cynical any more than it's automatically high-minded. Those two responses are merely opposite faces of the same coin. Fiction — good fiction, successful fiction — doesn't start out plumping for either virtue or evil. Fiction investigates characters' motivations to find their seams and contradictions as well as their unexpected moments of harmony. To do less is to sell both art and truth short.

This isn't to say that I think good literature requires perpetually tawdry characters; good literature isn't automatically cynical any more than it's automatically high-minded. Those two responses are merely opposite faces of the same coin. Fiction — good fiction, successful fiction — doesn't start out plumping for either virtue or evil. Fiction investigates characters' motivations to find their seams and contradictions as well as their unexpected moments of harmony. To do less is to sell both art and truth short.

Let's say a person wants to write a story demonstrating that godly people defend their faith. No sooner has our writer defined her task than characters and situation are flattened, because everything that happens in the story must illustrate how our main character, busily uplifting faith, is godly. It sounds awful even in concept, doesn't it?

A very different imaginative environment is created if a person — let's say Philip Roth — begins a story about a new Jewish recruit at boot camp, struggling to sort out cultural expectations and his own faith while being watched by his sergeant. By focusing on the specific pressure that faith and culture put on two well-defined characters, Roth is able to write an immense, genuinely great story about the pain of assimilation, the demands of patriotism, the particular clash between two recognizable human personalities — and how godly people defend their faith. That story is called "The Defender of the Faith," and it is one of the superb literary accomplishments of the 20th Century, in part because it's willing to look at faith not as an automatic good, but as a product of the human mind, susceptible to manipulation and skepticism.

For some believers, this definition is going to make literature seem hostile to faith. I don't think it is. I think that literature is a healthy sparring partner to faith, allowing the faithful to try on new postures and attitudes. And I think that is precisely what a believer, at least a stealth believer like me, is called to do. Not to ask questions in order to disprove the relevance of faith, but to prove faith's durability.

If I enter into writing by saying, "I am a Christian!", I have very little room to move imaginatively. All the space has been taken up by the huge, bulky apparatus of Christianity. If I enter into writing by saying, "What would happen if a priest suffering a crisis of faith were forced by circumstance into a close relationship with a struggling parishioner?", I have a lot more space to explore. In that space, I hope to find Christ's love in some guise I might not have expected before I started writing the story.

I love that, the possibility of finding Christ's love in some new guise. Is there an example of that you'd be willing to share? An aspect or incarnation of Christ's love that became available to you specifically through your engagement with literature — either as a writer or as a reader?

There are so many! One aspect of my stealth Christianity is how often I assigned glorious books and stories about faith in my classes. These were English classes, so we stuck to talking about craft and symbolism, but I always hoped that I was sneaking a little bit of extra nourishment into the reading. A great example is Graham Greene's peerless The Power and the Glory, a novel about a Catholic priest under persecution in Mexico in the 1930s. The priest is an alcoholic and a coward and has fathered a child, and Greene patiently reveals him to be a man of staggering spiritual depth. Not only is that novel a model to me of what literature can do at its best, but every time I read it, I am filled with frightened hope. I made you read it, didn't I?

Yes, you did, and I'm still grateful; the whiskey priest is forever seared into my heart and mind. Let's rewind a bit. You grew up in the Church. Did you also grow up writing? I'm wondering how, if at all, your faith journey shaped your artistic vocation. Was there a point when you felt "called" to write?

Oh, heavens, no. Writing seemed like so much work. I liked to read a lot better. But the time came that I had to get a job, and nobody would pay me to read. People would, it turned out, pay me to teach writing.

Yes, I imagine there are hordes of English majors out there who suffered shock when they realized that no one would pay them to read great books! So you spent your career teaching in secular universities. What was that like, given the fact that we live in a culture that's often neutral and even hostile towards religious faith? How can an artist working within a faith tradition navigate such an environment?

Be sneaky. Things aren't nearly as bad as they were twenty years ago, when open hostility to religion was the rule of the day. To confess to being a Christian in those charged times was to self-identify as a backward-looking moron. Institutions — magazines, universities, foundations — are considerably more open to Christianity now, though there's still a knee-jerk suspicion of Christians, who sometimes need to prove that they don't want to throw bombs at Planned Parenthood clinics before they'll be fully accepted.

A lot of the fundamental challenges of Christianity — how do I clear the path to God's kingdom on earth; how do I learn to extend real hospitality to my enemy — don't need to be couched in traditionally Christian settings. If I want to explore the difficulty of loving the family member who sets my teeth on edge, I can write a story that explores the cost of charity. Readers will, I hope, see Jesus's lessons in action. Interestingly, the great American fiction writer Flannery O'Connor used exactly the same tactic, but thought she was being loud and eye-catching, not sneaky. Shows you how sixty years can change context.

As a professor of creative writing, you've advised many young writers of faith over the years. Do you believe Christian writers face unique challenges when they sit down to write? Are there common pitfalls you advise students against? Dangers?

The biggest pitfall is the same as the biggest danger, and that is to let faith shackle imagination. Often Christians new to writing are terrified of straying from catechism, and so their writing becomes mannerly, obedient, and dull. A character might transgress — say, shoplift a lipstick — but then a strong but gentle second character, full of forbearance, will step forward, show the shoplifter the error of her ways, and the shoplifter ends the story chastened but happy. This kind of tale has, as far as I can tell, zero to do with most human interactions.

God made us, and knows better than we do what we are capable of. A glance at the front page of the newspaper any day makes it clear that all the time people are coming up with options for behavior that never would have occurred to me; whatever I write in a story isn't going to shock God. But I believe that God is glorified when we deliver our full strength in art, which means our full imaginative strength. What if that shoplifter nods obediently at the lecture, promises to reform her ways, and then heads straight out and shoplifts again — a leather jacket this time? Doesn't that seem a lot more interesting and likely? Now God's got something to work with, and so does the writer, and so does the reader. Once a real battle is joined, everybody has a reason to care.

That makes perfect sense. "Only trouble is interesting," is a line I still remember from graduate school. Meaning, good literature can't shy away from complexity and conflict.

That makes perfect sense. "Only trouble is interesting," is a line I still remember from graduate school. Meaning, good literature can't shy away from complexity and conflict.

Because we are complex, conflicted beings. One reason that a certain kind of pious fiction — a kind that Greene mocks in The Power and the Glory — makes me angry is that it squashes human beings and takes away our infinite capacity for strange, unexpected actions. A Hasidic parable says, "God made man because He loves the stories." Isn't that wonderful? That right there makes it worth having a faith.

Absolutely. The possibility that God takes pleasure in our stories — both lived and written — is so wonderful. But that's God's pleasure. What about yours? Is writing a spiritual practice for you? A form of nourishment? Or, to ask the bigger question, how is God present to you when you write? Are there ways in which writing fiction, specifically, reveals God?

This is an essential question for me. I grew up in California in the 1960s and '70s, surrounded by people who were quick to proclaim their spirituality and equally quick to deride traditional faith practices. Druids were fine; Sunday school was not. I knew a lot of people who said that their writing was their worship, and I had nothing but disdain for those people. Still, I'm afraid, do. For many years I maintained a very high wall between my prayer practice and my writing time.

I'm starting to suspect that I have been foolish to do this. God is surely not contained to my prayer time. God is present when I chop tomatoes for dinner, and when I walk the dogs, and therefore also when I write, right? To the extent that I am able to acknowledge and praise God in all I do, I hope that I am pleasing God. And for Pete's sake, why would I want to close God out of my writing life? I need all the inspiration I can get.

Writing fiction is a way to live another life, and when it's done well, it allows both reader and writer to experience pressures and rewards that we might not have guessed. To do this — to channel the experience of a character whom you are making up on the spot — requires a specific, infused kind of imagination that might be godly. Certainly St. Ignatius Loyola knew all about this kind of imagination when he created the Spiritual Exercises. If they aren't divinely inspired, they're the next thing to it.

Yes, let's talk about the imagination a little bit. I didn't grow up in a Christian tradition that valued it much. Our currency was doctrine, not "flights of fancy." Why is the imagination important to a life of faith? If you could make a case for art/literature as essential to a vital Christianity, what would that case be?

Fancy doesn't need to fly. Fancy is often earthbound, trudging along in close companionship with the imagined human being who is struggling with normal human pain or difficulty — grief, maybe, or yearning, or resentment. Imagination allows us to pour ourselves into that imagined person. If we enter into a scene imaginatively, we don't stand back at a sanitary distance and make judgments about what the character should do. We become the character, we feel and react with him, and we are therefore enlarged because we've seen an aspect of our own souls that we hadn't seen before.

Some years ago I published a novel about my grandmother, who abandoned her young children and ran away. After the book came out, I talked to book clubs, and many readers told me that they wouldn't read my book because they didn't believe mothers should abandon their children. Well, neither do I. I wrote the book to explore what would drive a woman to do such a thing, and what were the consequences. I came away, as I hope my readers did, with a deeper compassion. Isn't that what God requires of us?

Art is essential to a vital Christianity because it changes and provokes our view of a world that God created, and that is larger and more various than we want to admit.

It sounds like you're talking — at least in part — about empathy. The ability to enter into another person's emotional and spiritual reality. There's been a lot of public debate about this in recent years. About whether art — literature, film, etc. — can make us more empathetic. I suppose the larger question here is about what art can do. What value it holds in the "real world." Any thoughts?

It's possible that I'm talking about empathy, but I think of it as acting. Around the house I keep copies of Stanislavsky's An Actor Prepares, the Gospel of Method Acting. The book is a wonderful source of exercises to help a person drop into the entire existence of someone else — the physical reality as well as the psychic one. This explains why I might spend some of my writing time rolling around on the floor, or gazing at the way I lift a glass of water. Stanislavsky encourages using the body as a means to explore a character's mind and history, and those things to reveal story. When I'm deeply inside a piece of fiction, I'm deeply inside a character, and I'm not asking, "What would X say here?" As X, I think what I am going to say. The difference in psychological and imaginative investment is big. When I emerge from that engagement, I don't feel more empathetic. Perhaps this is delusional, but I feel as if I have personal experience. Does it affect how I behave in the world? It sure does. My writing has made me a better person. That feels like a dangerous thing to say, and every day I see more clearly how much work I still have to do, but I think it's true.

It doesn't sound delusional. It sounds like the kind of deep engagement that opens us up. Makes us more roomy inside. And maybe that's a path to salvation. Speaking of, much of your fiction revolves around issues of belief, goodness, morality, and the weight of faith (religious or not) on individual lives. As a writer shaped by the Christian narrative of redemption, do you feel compelled to write redemptive stories? To "save" your characters?

Ha. My poor, beaten-up characters probably wish that once in a while I'd save them. My stories tend to end on a point of new insight for the character, and as you know, insight isn't always especially reassuring.

All those Californians I grew up with tended to be very big on redemption, though they wouldn't use that word. They believed in do-overs and personal re-creation, not being tied to the mistakes of the past. I can't start to tell you how many times people presented themselves, proudly announcing that they had been made new — usually by therapy, sometimes by a colonic. That newness would last a few months, until the next breakthrough. As a result, I am skeptical of claims of home-made renewal or redemption, and on the alert for the various forms of self-delusion we take on so ardently — and I am first among sinners in this regard. I'm forever finding my own sins in my characters, and it is my job to point those sins out to them and to myself, over and over. Awareness isn't the same thing as redemption, but maybe it makes redemption possible. At least if my illusions are stripped away, I can see what is actually needful. On a good day, I might be grateful for that.

Eugene Peterson writes about "a long obedience in the same direction." What you're saying about awareness and redemption sounds similar. Conversion as a lifelong process of stripping away, seeing anew, and trying again. I like the idea of having literature as a companion on that long journey.

Eugene Peterson writes about "a long obedience in the same direction." What you're saying about awareness and redemption sounds similar. Conversion as a lifelong process of stripping away, seeing anew, and trying again. I like the idea of having literature as a companion on that long journey.

Yes, yes, yes. I wish I had the elegance of Eugene Peterson. The conversion continues daily. It stays interesting, even though sometimes it stings.

Since we're "people of the book," I have to ask you this last question. How would you characterize your relationship with the Bible? Is "The Book" important to you as a writer of fiction? What about religious language (liturgy, hymnody) more broadly?

The Bible and I are cordial, but we are not fast friends. In the Catholic church I grew up in, the Bible was not central. I didn't read it Genesis to Revelation until I was in my 20s, and found the experience more baffling than revelatory, though it helped explain a lot of literary references I hadn't understood. The language of Catholic liturgy, though, is burned into my marrow, and that sense of communal prayer — prayer that lifts up a single believer — is precious to me.

Erin, this has been a fascinating conversation. Thank you again for exploring these questions with me. It was a pleasure to have you back at JwJ.

Thank you. I rarely know what I think until I say it, so this has been an exploration for me, and a treat.

Image credits: (1) dialbforblog.com; (2) Blogspot.com; and (3) dialbforblog.com.