The following interview by John Sides is posted by permission from the Washington Post (August 15, 2016). Sides is an Associate Professor of Political Science at George Washington University. He specializes in public opinion, voting, and American elections. Robert P. Jones is the founding CEO of the Public Religion Research Institute (PRRI), and the author of the new book The End of White Christian America (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2016). Note that the interview was published three months before the American presidential election.

Let’s start with a graph from the book. I think this won’t strike many readers as surprising, but tell us what you see and how you interpret it.

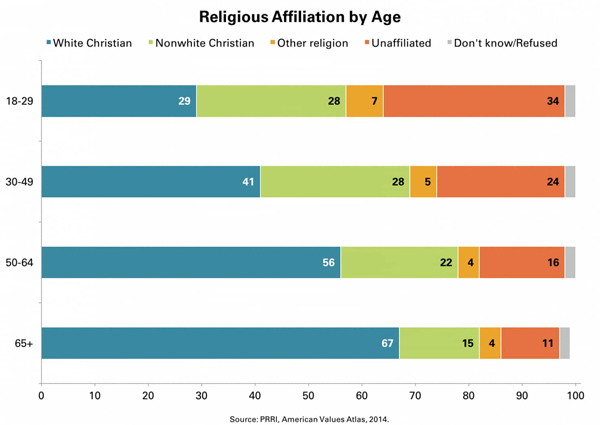

The chart below reveals just how quickly the proportions of white, non-Hispanic Christians have declined across generations.

Like an archaeological excavation, the chart sorts Americans by religious affiliation and race, stratified by age. It shows the decline of white Christians among each successive generation.

Today, young adults ages 18 to 29 are less than half as likely to be white Christians as seniors age 65 and older. Nearly 7 in 10 American seniors (67 percent) are white Christians, compared to fewer than 3 in 10 (29 percent) young adults.

Although the declining proportion of white Christians is due in part to large-scale demographic shifts — including immigration patterns and differential birth rates — this chart also highlights the other major cause: young adults’ rejection of organized religion. Young adults are three times as likely as seniors to claim no religious affiliation (34 percent versus 11 percent, respectively).

What’s the broader implication of this generational pattern?

The American religious landscape is being remade, most notably by the decline of the white Protestant majority and the rise of the religiously unaffiliated. These religious transformations have been swift and dramatic, occurring largely within the last four decades. Many white Americans have sensed these changes, and there has been some media coverage of the demographic piece of the puzzle. But while the country’s shifting racial dynamics are certainly a source of apprehension for many white Americans, it is the disappearance of White Christian America that is driving their strong, sometimes apocalyptic reactions. Falling numbers and the marginalization of a once-dominant racial and religious identity — one that has been central not just to white Christians themselves but to the national mythos — threatens white Christians’ understanding of America itself.

One thing you describe is how the decline of white Protestantism isn’t just about the decline of mainline denominations like the Episcopal, Methodist or Presbyterian Churches. It’s also about the decline of evangelical Protestantism. This conventional wisdom that traditional Gothic cathedrals are empty but the suburban mega-churches are bursting isn’t quite right.

Up until about a decade ago, most of the decline among white Protestants was confined to mainline Protestants, such as Episcopalians, United Methodists, or Presbyterians, who populate the more liberal branch of the white Protestant family tree. The mainline numbers dropped earlier and more sharply — from 24 percent of the population in 1988 to 14 percent in 2012, at which time their numbers generally stabilized.

But over the last decade, we have seen marked decline among white evangelical Protestants, the more conservative part of the white Protestant family. White evangelical Protestants comprised 22 percent of the population in 1988 and still commanded 21 percent of the population in 2008, but their share of the religious market had slipped to 18 percent at the time the book went to press, and our latest 2015 numbers show an additional one-percentage-point slip to 17 percent.

These indicators of white evangelical decline at the national level are corroborated, for example, by internal membership reports during the same period from the Southern Baptist Convention, the largest evangelical Protestant denomination in the country. It has now posted nine straight years of declining growth rates.

As a result, both white mainline Protestants and white evangelical Protestants are graying. In 1972, white Protestants’ median age was 46 years old, only slightly higher than the median age of the American population (44 years old). Today, white Protestants’ median age is 53, compared to 46 among Americans as a whole. Notably, by 2014, there was no difference between the median ages of white evangelical and mainline Protestants.

What about Catholicism? You focus on the decline of white Protestantism. Where do Catholics fit in this story?

Catholics simply do not fit neatly into the story of White Christian America. In the book, I use White Christian America as a metaphor for the dominant cultural and institutional world built primarily by white Protestants, which until recently set the terms and tone for national debates and served as a kind of “civil glue” for the country, to borrow a term from E.J. Dionne.

While anti-Catholic sentiment has generally cooled today, it remained strong up through the 1960s, as President John F. Kennedy’s campaign demonstrated. In the 19th and early 20th century, many Catholics were seen as neither “white” nor “Christian.” For example, Irish immigrants were often classified by U.S. immigration officials not as “Caucasian” but as “Celts.” And even the more liberal mainline Protestants saw Communists and Catholics as the twin threats to American democracy up through the middle of the 20th century.

I think the decline in the “white” part of “White Christian America” is well known, given the country’s obviously increasing ethnic diversity. But let’s talk about the decline of the “Christian” part and particularly the increasing number of people who aren’t affiliated with any religious tradition. Why are the ranks of the unaffiliated increasing?

The rise of religiously unaffiliated Americans over the last few decades is one of the most important and dramatic shifts in American religious history. As recently as the 1990s, less than 1 in 10 Americans claimed no religious affiliation. By 2014, the religiously unaffiliated rivaled Catholics’ share of the religious marketplace, with each group making up 22 percent of the American population.

Looking ahead, there’s no sign that this pattern will fade anytime soon. By 2051, if current trends continue, religiously unaffiliated Americans could comprise as large a percentage of the population as all Protestants combined — a thought that would have been unimaginable just a few decades ago.

The reasons for the growth of religiously unaffiliated Americans are complex. First, it should be noted that the growth of this group has come almost entirely at the expense of white Christian denominations, both Protestant and Catholic. African American Protestants have maintained their market share, and the ranks of Latino Catholics, Latino Protestants and Asian-Pacific Islander Protestants have been growing.

When PRRI surveys have asked religiously unaffiliated Americans who were raised religious why they left their childhood religion, respondents have given a variety of reasons — stopped believing in teachings, conflicts with science, lack of time, etc. — but one issue stands out, particularly for younger Americans. About 70 percent of millennials (ages 18-33) believe that religious groups are alienating young adults by being too judgmental about gay and lesbian issues. And 31 percent of millennials who were raised religious but now claim no religious affiliation report that negative teaching about or treatment of gay and lesbian people by religious organizations was a somewhat or very important factor in their leaving.

You are not particularly sympathetic to the perspective of the “New Atheists,” like Sam Harris or Richard Dawkins. But you could imagine that they’d read your findings about the growth in the religiously unaffiliated as a vindication. After all, why would the ranks of the unaffiliated be increasing if they weren’t fundamentally skeptical about the existence of God, or deeply opposed to theistic religion generally? Are the unaffiliated really non-believers? What does PRRI’s data tell us about them?

The rising number of religiously unaffiliated Americans has more to do with people being less likely to claim a formal connection with organized religion than it does with widespread doubts about the existence of God. While there has been an uptick in the number of Americans who identify as atheist or agnostic, this has not been the main driver of growth of the religiously unaffiliated.

As the number of religiously unaffiliated Americans has increased, so has the internal diversity of this group. PRRI’s 2014 American Values Atlas identifies three distinct subgroups among the unaffiliated: about half (52 percent) who describe themselves as secular or not religious, about one-quarter (24 percent) who describe themselves as religious (“unattached believers”) and about one-quarter (24 percent) who identify as agnostic or atheist. This is an evolving and complex group.

Many unaffiliated Americans, for example, still believe in God, even as they are happily unconnected to any church and show little interest in seeking out institutionalized religion. PRRI actually has a survey in the field right now to get a better portrait of this important group and should have updated numbers by the end of the month. Stay tuned.

It struck me that evangelical Protestantism comes in for particular criticism in the book. They are on the wrong side of racial integration and civil rights, particularly white Southern churches and especially Southern Baptists. They are on the wrong side of homosexuality and the rights of gays and lesbians. Indeed, you argue that they’re also far behind in acknowledging the end of “White Christian America.” So part of your message to them is that they should affirm gay marriage and racial equality — which are also positions associated with the political left. That seemed like, well, a hard sell!

I’m certainly critical of the way that white evangelical Protestants have historically intertwined racial segregation and Christianity. That’s a normative perspective, but I don’t take it to be a controversial one.

White evangelicals have themselves started disentangling Christianity and racism, albeit slowly and recently. For example, the Southern Baptist Convention did not get around to apologizing for the role slavery played in the denomination’s founding and for its consistent failure to support civil rights until 1995. And only this year, 2016, did the SBC vote to officially disavow the display of the Confederate battle flag.

There are important leaders, such as Russell Moore, the president of the SBC’s Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission, leading the way here, but there is a long road ahead toward anything like racial reconciliation. There is some progress, and at least a motivation among key white evangelical leaders, to take seriously the demands of addressing centuries of racial inequality. While the issue of racial inequality has without a doubt driven political polarization, I don’t see it as one necessarily owned by the political left.

The issue of LGBT equality is more complicated and more divisive. But even here, attitudes are shifting. Generational differences make it clear that opposition to gay rights will ultimately lose its power as the culture war weapon of choice. Anti-gay rhetoric is unlikely to appeal to younger religious Americans, regardless of their religious affiliation.

For example, 45 percent of young evangelicals (ages 18-29) and 43 percent of young Mormons favor same-sex marriage, compared to only 19 percent of white evangelical seniors and 18 percent of Mormon seniors. Most notably, the data show that young Republicans have passed the tipping point: 53 percent of young Republicans now support same-sex marriage.

Maybe I can push you even more on this point. One route you see for a revitalized Christianity is for it to be less white — that is, for individual church communities to be more racially and ethnically diverse. Certainly the “segregation of Sunday mornings” is and has been a perennial concern. But the churches you describe that fit this mold — Middle Collegiate Church in New York City and Oakhurst Baptist Church in Atlanta — are also churches where it appears that the majority of members are, essentially, pro-gay and outraged by the deaths of black men like Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown and Eric Garner. So, again, it seems like your recipe for a more vital American Protestantism also coincides with a progressive political agenda.

Embedded in this question is whether being concerned about the equal treatment of African Americans by police and supporting the equal application of laws to gay and lesbian citizens is circumscribed to a progressive political agenda. I think younger evangelicals and younger Republicans are increasingly challenging the assumption that equality before the law is a progressive value.

Also, it’s important to note that neither of these two churches started off as successful multiracial congregations and neither historically held particular concerns about racial inequality or gay rights. The key decision for both churches was that, as the areas were changing around them, they decided to stay put and be committed to being a neighborhood church, regardless of the racial and ethnic composition of the neighborhood.

For example, in 1963, the then all-white Oakhurst Baptist Church received an award from the Southern Baptist Convention for being the model church of the year — certainly not an award given for being progressive. But the decision to stay in the neighborhood slowly transformed the membership’s conceptions about racial inequality and, later, LGBT rights. In other words, they didn’t start off with an ideological commitment but with a basic decision to be a church to the neighborhood. The other changes flowed organically from that basic commitment.

There’s a real irony in the timing of this book. It’s being published in the middle of a presidential campaign in which several Republican candidates — and especially Donald Trump — have embraced what you call the “white Christian strategy.” You describe it as “an outgrowth of the Southern strategy” that used racially coded messages to appeal to whites. You also say that it is “a sentimental vision of midcentury heartland America” and “a narrative of cultural loss.” You say that, politically speaking, this strategy amounts to an “outdated playbook.” But it seems to be Trump’s playbook. What’s going on?

I completed the final text of the book in the early fall of 2015, just as Donald Trump was announcing his candidacy, and the book does not mention Trump at all. But I do think the book casts some much-needed light on white evangelicals’ attraction to Trump.

I first identified the roots of this unlikely alliance back in a February column for the Atlantic, just after Trump won the GOP South Carolina primary, where nearly 7 in 10 voters were white evangelical Protestants. Trump’s appeal to evangelicals was not that he was one of them but that he would “restore power to the Christian churches” if he were elected president. This explicit promise, along with his anti-immigrant and anti-Muslim rhetoric, signaled to white evangelical voters that when he crowed about “Making America Great Again,” he meant turning back the clock to a time when conservative white Christians held more influence in the culture. Trump has essentially converted these self-described “values voters” into “nostalgia voters.”

The surprising ascendancy of Trump in the Republican primary, with his strategy of making strong appeals to a white Christian base, is also shaping up to be a test of a key argument I make in the book — that Mitt Romney’s 2012 campaign was the last campaign that could plausibly follow a “white Christian strategy” to the White House. So it looks like we’ll see whether I called that one too early or not! But even if Trump somehow manages to pull off a win by bringing out unprecedented numbers of white Christian voters, the patterns in the electorate are clear. Every four years, there is a shrinking pool of white Christian voters; if current trends continue, 2024 will be the first year white Christians will not make up a majority of voters nationwide.

I think my questions here reflect a little uncertainty about one of your more optimistic arguments. As you note, religiosity and partisanship have become increasingly tied together. Christians — or at least white Christians — and Republicans are increasingly the same people. You see this as lamentable. You want there to be a “new political playbook” that serves to loosen these ties between race, religion, and partisanship. Maybe I just see these ties as stronger than you do, or maybe I am just a little unclear on what this new playbook would look like. How do you think we can get to a world where how often you attend church doesn’t predict whether you identify as Democrat or Republican?

One preliminary point: The supposedly strong link between church attendance and partisanship deserves an asterisk. First, this relationship holds most strongly only among white, non-Hispanic Americans. It’s virtually nonexistent among African Americans, who attend religious services at comparable levels to white evangelicals and identify overwhelmingly as Democrats. The relationship is also is significantly muted among Hispanics.

Second, at least among Protestants, the top end of the traditional response categories this question employs (“more than once a week”) is biased toward evangelical Protestants. White evangelical churches offer multiple services per week and have internal expectations of higher attendance levels, while many white mainline churches only offer one service per week and the internal expectations are generally lower. A person who attends religious services once a month might be considered a solid member at a mainline congregation, but they might be put on the backsliding visitation list at an evangelical congregation. The upshot is that this measure may be capturing more identity than behavior.

My argument for a “new playbook” rests less on optimism and more on what will simply be necessary for the future success of any political party. The Republican Party’s post-mortem analysis of Mitt Romney’s 2012 loss, which came to be known as “the autopsy report,” was a serious reckoning with the realities of the changing demographics in the country. It concluded with a blunt call to move away from the Southern strategy that used race as a wedge to appeal to white Southern voters and to abandon anti-immigrant rhetoric in favor of comprehensive immigration reform that included a path to citizenship.

Of course, the Trump campaign has completely ignored these recommendations, so we are not seeing the impact of this new playbook. However, if the GOP wants to have a future as a national party, and not just the party of white Christian nationalism, it will have to find a way to move in these directions. Particularly if Trump loses, the Republican Party will almost certainly revisit these big-tent recommendations. And if they get implemented, it will provide some new openings for realignments along racial and religious lines.

There is an air of finality about your analysis, which is captured in the book’s title. But one other way of looking at the broad sweep of American religious history is to think in terms of cycles. So rather than definitive beginnings and endings, we might expect periods of decline followed by awakenings or reawakenings. Is such a cycle possible anymore? Could we expect a religious reawakening in this country, and what might that look like?

I begin the book with an obituary for White Christian America, and I conclude the book with a eulogy. This construction is consistent with the book’s stark title. My argument in the book is that we have already experienced the passing of White Christian America. While this claim is grounded in demographic changes, it is also supported by the fading power of major institutions, such as the National Council of Churches or the Christian Coalition of America. There are no indicators that the country will see the likes of White Christian America as a dominant cultural force again.

None of that analysis precludes the possibility of religious reawakening. But rather than a reassertion of any single religion’s power and influence, we would — and do — see that expressed today in a variety of ways: in diverse churches, but also in synagogues, mosques, temples, meditation centers and others.