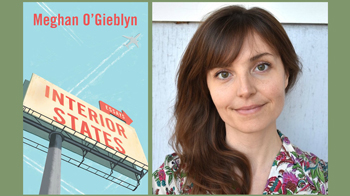

It's crazy to think that a girl who was home schooled until the tenth grade in a fundamentalist family, spent her summers in Bible camps, and attended Moody Bible Institute, now writes a monthly column for the Paris Review called "Objects of Despair." But so it is. In her debut collection of fifteen essays entitled Interior States (2018), Meghan O'Gieblyn explores the "interior states" of the Midwest where she grew up, and her Christian faith that she has lost. This interview with Nathan Goldman appeared in the Los Angeles Review of Books (November 3, 2018), and is used by permission.

Nathan Goldman is a writer living in Minneapolis. His work has appeared in The Nation, Literary Hub, The New Inquiry, and other publications. He is a blog editor for Full Stop.

NATHAN GOLDMAN: The essays that comprise Interior States span a considerable period of time — the earliest was published in 2011; the latest, this year. The majority appeared sometime between 2016 and now, but even so, I was struck by the sheer variety of ways in which the essays address your central concerns. At what point in the composition of these pieces did you begin conceiving of them as a unified project? Does having this body of work now collected and presented as something singular change how you think about the essays?

MEGHAN O’GIEBLYN: When I first started writing essays, around 2011, I had a dim idea that I wanted to write a collection and was quickly informed, by practically everyone who seemed to know anything about publishing, that collections are impossible to sell, particularly for a first-time author. Several people advised me to try linking my essays together into something that might pass as a memoir, and I tried this for almost a year before giving up. Part of the problem was that a memoir would have required me to tell the definitive story of how I left Christianity. I dreaded that finality. What I love about essays is the way you can approach an experience from a very particular angle, and the fact that you can keep returning to it across different essays, taking different approaches. Essays allowed me to circle that experience, over and over again, much the way certain contemplative or mystical theologians try to capture the nature of God through a series of negative or positive comparisons, while avoiding direct statements about the Divine nature itself.

MEGHAN O’GIEBLYN: When I first started writing essays, around 2011, I had a dim idea that I wanted to write a collection and was quickly informed, by practically everyone who seemed to know anything about publishing, that collections are impossible to sell, particularly for a first-time author. Several people advised me to try linking my essays together into something that might pass as a memoir, and I tried this for almost a year before giving up. Part of the problem was that a memoir would have required me to tell the definitive story of how I left Christianity. I dreaded that finality. What I love about essays is the way you can approach an experience from a very particular angle, and the fact that you can keep returning to it across different essays, taking different approaches. Essays allowed me to circle that experience, over and over again, much the way certain contemplative or mystical theologians try to capture the nature of God through a series of negative or positive comparisons, while avoiding direct statements about the Divine nature itself.

Because I’d been told it was impossible to sell collections, I didn’t think of these essays as a unified project until very late in the process — essentially until I was contacted by Gerry Howard at Anchor, who asked whether I had thought about collecting the pieces. And it was really his encouragement and enthusiasm for the project that made me realize it could be a book. Some of the subject matter that I’d considered discrete — I had several essays on the Midwest and several others on Christianity — were actually linked by similar concerns. For one thing, the form of evangelicalism I was writing about was very distinctive to the Midwest and grew out of the theology of Midwestern evangelists like D.L. Moody. I also realized that what I was writing about, across these essays, was the experience of loss, particularly the loss of telos. The directionless feeling that I felt after leaving my faith is analogous, in some sense, to what many people in the Midwest are feeling at a moment when the industries and ideas that built the region — manufacturing, the American dream — have begun to seem tenuous and uncertain. So there is, I think, an underlying unity to the book, but that unity is evidence of my own intellectual obsessions rather than any deliberate strategy.

I liked that, in addition to the note in the front of the book that mentions the publications in which the essays initially appeared, each original publication is listed — along with the year of publication — at the end of each piece. This practice helped me to understand the book as something heterogeneous as well as a whole. And, because it made clear that the essays are not arranged chronologically, I felt it freed me from mistakenly reading the book as structured around a temporal progression. Possibly I’m reading too much into this subtle choice, but: was that your decision? If so, what was the reasoning behind it?

Yeah, it was my decision to include those details. The essays do represent, as you mention, an evolution in my thinking, so I wanted to ensure that readers understood which ones were earlier and which were later. And because some of the essays are tied to cultural and political events, I felt it was important to signal what was happening when the piece was written. So much has changed in the Midwest, and in the country as a whole, over the past few years, so I wanted to announce, for example, whether an essay was written before or after the 2016 election. I’m not sure if the publications are as crucial for readers to know. That may have been a sentimental gesture on my part, since I really value the relationships I’ve developed with these magazines over the years. I feel very grateful that magazines like this one, like Boston Review, Guernica, and especially The Point (where three of the essays in the collection were published) provided a platform for my early essays, and that the editors at those venues allowed me to do work that was, in retrospect, fairly ambitious for a beginning writer.

In the preface, you link your project as an essayist to the evangelical tradition of “testimony,” which you contrast with another Christian lineage of “confession” associated with the personal essay. Do you see your use of your own life in your essays as at odds with that other, more confessional lineage?

Around the time I was pulling the collection together in manuscript form, there was a rash of criticism — several pieces that appeared within a month or so — on confessional writing, arguing that recent memoir and personal essays were gratuitous and self-indulgent. This happens every few years, and the complaint, of course, is a very old one. But as I was reading those arguments, I began thinking about confession as a religious term and a religious posture, and what struck me was that it was completely foreign to my experience as a protestant, evangelical Christian. We didn’t practice confession as a ritual…

To continue reading, click here.

Dan Clendenin: dan@journeywithjesus.net