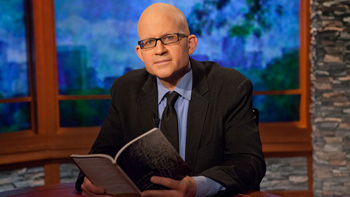

Christian Wiman (born 1966) is an American poet, the author of seven books, and from 2003 to 2013 the editor of the journal Poetry, the oldest poetry magazine in the United States. On his thirty-ninth birthday, he was diagnosed with a rare form of cancer. His many treatments included a bone marrow transplant. At about the same time, Wiman fell madly in love with and married his wife, Danielle. Today they have two children. Percolating underneath all of this was a long latent faith from his childhood days in West Texas. Since 2013 Wiman has taught at the Yale Divinity School and Yale Institute of Sacred Music. His most recent book is Joy:100 Poems (New Haven: Yale, 2017).

This interview by Krista Tippett originally aired on her show "On Being" on April 12, 2012, and was later updated and reposted on January 4, 2018. Used by permission.

Krista Tippett, host: Christian Wiman is a writer who has come to give voice — to his own surprise — to the hunger for faith and the challenge of faith for people now. His Texas upbringing was soaked in both a history of violence and a charismatic Christian culture. He wasn’t formally religious for years after he left home, lived all over the world, and became a poet. Then, when he was in his late 30s, he married the love of his life, found God again, and was diagnosed with an incurable, unpredictable cancer. So Christian Wiman is more aware of his mortality than most of us, and he’s bearing a kind of poetic witness to something new happening in himself and in the world.

Christian Wiman: I am convinced that the same God that might call me to sing of God at one time might call me, at another, to sing of godlessness. Sometimes, when I think of all of this energy that’s going on, all of these different people trying to find some way of naming and sharing their belief, I think it may be the case that God calls some people to unbelief in order that faith can take new forms.

Christian Wiman: I am convinced that the same God that might call me to sing of God at one time might call me, at another, to sing of godlessness. Sometimes, when I think of all of this energy that’s going on, all of these different people trying to find some way of naming and sharing their belief, I think it may be the case that God calls some people to unbelief in order that faith can take new forms.

Ms. Tippett: Christian Wiman is a professor in religion and literature at the Yale Institute of Sacred Music. He’s published several volumes of poetry and prose; most recently, Hammer Is the Prayer. I spoke with him in 2012, when he was the esteemed editor of Poetry magazine. He’s a prolific writer of essays that are philosophical or theologically reflective and always, in their own way, both honest and poetic.

One called “The Limit,” for example, begins with this arresting sentence: “I was 15 when my best friend John shot his father in the face.” But details of that shooting, at which he was present, and of Christian Wiman’s own destructive anger as a child, mingle with observations like this: “It was nearly dusk, my favorite time in west Texas, the light like steeping tea, shadows sliding out of things.”

Ms. Tippett: I always talk to people about this, and I’ve heard and read a lot of stories about the interesting ways religion and spirituality get communicated to us as children. I have to say, Christian, that your story, of all of them that I’ve heard all these years, is the most familiar to me: growing up absolutely immersed in this religious universe, which meant everything.

Mr. Wiman: Right.

Ms. Tippett: But then, when I left that place — and like you, I went far, far away — the religious piece stopped to make sense, as well, because it was the whole package.

Mr. Wiman: I think, for me, it was a big loss. I didn’t realize exactly how large a loss, for years, because I just — like so many people — dispensed with it and became an agnostic or whatever you want to call it. But I wonder; I’ve got little kids now, and I do think about what I should teach them and how I should teach them, in terms of their spiritual lives, because I greatly value the way I was raised, which was completely immersed in that culture.

Ms. Tippett: Did you go to church twice on Sunday, and Wednesday night?

Mr. Wiman: Yep, yep; sometimes, even more. And we had to learn Bible verses and say them over the meals.

Ms. Tippett: And the hymns, the singing.

Mr. Wiman: We knew the hymns and had the singing. And there was no possibility of puncture to that world. I never met anybody who didn’t believe, until I went off to college. Never met a soul. And I value the coherence of it, and I value the intensity of it and the momentum that it’s given my life. But it’s also created all kinds of difficulties, as I’m sure you know.

Ms. Tippett: I think there are a lot of people like us, though, in this country, and especially in, I don’t know, what we call the Bible Belt. But I’m not sure — when you get outside the Bible Belt, I’m not sure it’s a narrative people recognize.

Mr. Wiman: I think that’s true. I have discovered that there is an enormous number of people in this country who are — they have some kind of religious language that they’re just unhappy with. It doesn’t accord with their feelings of the sacred or their feelings of what spirituality means, and they’re casting about for some new way of believing. And yet, you can’t just jettison everything that you have.

Ms. Tippett: I also wonder about the origins of your life as a poet. In one of your essays, you start by saying that when you were 20 years old, you set out to be a poet. But I guess I’m curious too, about where you see the inklings of that, or the impulses or hungers or habits that were there earlier in your life, that then somehow came to life at that point, when you were 20.

Mr. Wiman: Well, I certainly wrote, when I was a little kid; I just didn’t really know that they were poems. My mother is a creative person. She would paint, and she would write things herself. We weren’t a family that read; there weren’t books around. But I did try to emulate the hymns that I heard, and I would write these little fragments of things and little songs. And in fact, when we were — I think I was six or seven years old, we went to the First Baptist Church in Dallas, which, at the time, was the largest Baptist Church in the world. I don’t know if it still is, but it took up four city blocks, was this massive place.

And the guy’s name was Brother Cristobal. I forget his first name. But they published the Southern Baptist newsletter out of there, and it was just this enormous place. And at the end of the service, they would have what I’m sure you grew up with — they would have the call for people to be saved. And people would flood the aisles at this place, because there were thousands of people in the congregation. So one day, when I was six or seven years old, I left my family and ran down there. Didn’t even tell them. They thought I was going to get saved. And I just handed him a poem that I had written, and the poem was, “I love the Lord, and the Lord loves me. I will not forget, and neither will He” — the whole thing.

Ms. Tippett: Wow.

Mr. Wiman: And then it turned up in the Southern Baptist newsletter. He published it. I turned around and ran back, and he published it in the Southern Baptist newsletter. And they had this little poem in there when I was — probably, my biggest publication. [laughs]

Ms. Tippett: [laughs] That’s right. And I would bet that you were the only editor of Poetry magazine who’s ever had his first poem published in the Southern Baptist magazine.

Mr. Wiman: That’s probably true. That’s probably true, although there have been editors who were very interested in theology. Henry Rago was very interested in theology.

Ms. Tippett: And then, of course, on another level, somewhere you wrote that your childhood was “the very forge and working-house of poetry.” In terms of the raw materials of drama and pathos and emotion, your childhood was — there’s so much violence in there, in your family.

Mr. Wiman: Well, I think — my family’s very chaotic, but I would not say that I had had a difficult childhood, compared to a lot of people I’ve seen since then, because I was loved by my family. And a lot of people grow up without love.

Ms. Tippett: Your mother watched her father kill her mother.

Mr. Wiman: Yeah, that happened when my mother was 14. She watched — her father came in and shot her mother, and my mother and her two brothers were sitting at the table. And then — it’s really an awful story. She turned around — my grandmother, her mother, turned around and said, “Oh, Fred, no,” and she realized what had happened — she got shot in the back. And the kids ran out, and then her father just lay down beside his wife and shot himself.

And my mother moved from place to place. That happened when she was 14 years old, and all those kids got separated. And they all came out — emerged out of that, but not psychologically intact.

Ms. Tippett: I suppose what’s just striking me right now, as we talk, is, that story gets told. And it’s very dramatic, about that murder. But really what’s astonishing about the story is, as you say, you were raised by this woman who went through that when she was 14. And she loved you. And that was this defining thing that she was able to do, despite that.

Mr. Wiman: Yeah, well, I was raised in a very masculine culture. I played football and went hunting, and I got in tons of fights when I was a kid. And I had that sort of masculine inclination and imperative in me and around me, all the time. But when I look back at my life, it’s my mother and my grandmother who really shaped me, both of them. It’s feminine consciousnesses that I responded to. And both of them — my mother is a more educated person than my grandmother, and my grandmother had a kind of consciousness that, really, it took me a long time to understand, because I think many people would simply say it was unconsciousness. She lived within that religious culture that we talked about that was completely saturated and defined by Baptist theology. But she also lived in her world in a way that is unlike anyone I’ve known since, actually. She knew her world down to the least flower, the least creature that was in her yard, and every person that was in her life. And it was a kind of passive consciousness — and I’d like to use the word “passive” without any pejorative meaning, but a kind of passive consciousness that seems to me, in some ways, exemplary. And I think poetry comes out of that.

Ms. Tippett: You say “passive,” but what I also think of is embodied consciousness, physical, incarnational, almost, you could say; that in consciousness, it all manifests itself in physical reality and is in touch with that.

Mr. Wiman: Yeah, I love that definition, actually. I think that’s a great definition of the way she was. And I have a — there’s a section in this book that is about her. Here we go. It says, “She who in her last days loved too well to lose / A single weed to namelessness, in creosote, / Blue gramma, goatsbeard that is not thriving, is, / Amid the cattails’ brittle whisper whispers / O, Law’, Honey, ain’t this a praiseful thing.”

Ms. Tippett: So one thing I really like in your poetry — and I think it connects, also, to your faith — is this real tie to reality, which also gets intellectualized, the notion of reality. Do you know what I mean? [laughs]

And I don’t know — when I was reading through you, I also found a lot of reference to reality from Simone Weil: “It is necessary to have had a revelation of reality through joy in order to find reality through suffering.” Or even in this essay you wrote, “Hive of Nerves,” you talked about Christ using metaphors, speaking “the language of reality in terms of the physical world.” So tell me about how you think poetry works with reality, uniquely.

Mr. Wiman: Well, I think — I’ve been sick, lately, and I actually had a bone marrow transplant and was in the hospital for quite a long time. And one of the things — poetry died for me, for a while. I found that it just wasn’t speaking to me. And I think I had certain expectations that it took me a while to realize were false expectations.

I think we often talk about poetry getting us beyond the world, taking us to the very edge of experience and then getting us into the ineffable. And I have to say, when I was faced with the actual ineffable, I didn’t want poetry that gave me more of the ineffable. What I wanted was some way of apprehending the world that was right in front of me that was slipping away. I wanted the world in front of my eyes. And the poems that I found useful were absolutely concrete: sometimes not at all about religious things and not at all about spiritual things, but simply reality, and reality rendered in such a way that you could see it again.

There’s a great quote from the mid-20th century literary critic, R.P. Blackmur. He’s talking about John Berryman. He said that his work “adds to the stock of available reality.” It added to the stock of available reality. And that’s a good way to think about what a real poem can do. It suddenly makes the amount of reality that you have in your life greater. You’re able to apprehend more of it.

Ms. Tippett: Recently, I was talking to a physicist, a string theorist who’s working with a new kind of mathematical language. And the analogy we were talking about is the difference between poetry and prose, so the fact that there are truths you simply can’t convey in a factual sentence. And it seems, possibly, that there are physical realities that you can’t convey with an equation, but that a more visual mathematics might be able to convey.

Mr. Wiman: Gosh, that’s interesting. I think that’s why physics is so fascinating to so many of the poets, to contemporary poets, these days. There is some kind of reality that’s being revealed that we can only reach through oblique ways. I think it reaches way back. It’s why I’m drawn to mystics like Meister Eckhart — and more contemporary ones, like Simone Weil; and language of apophasis, where you state something, but the statement sort of un-states itself so that Meister Eckhart said, “We pray to God to be free of God.” We ask God to be free of God.

I don’t think he wanted to give up his religion. The idea wouldn’t have occurred to him. But he wanted to give up that idea of God as being this thing outside of our consciousness. And I think one thing poetry can do is take us to those places where reality slips a bit; what we think of as reality slips a bit, like those equations in physics, and suddenly we’re perceiving something differently than before. And it’s not all airy-fairy mysticism either. It’s quite angular and hard, hard-edged, and that’s what I think the analogy is with physics and with physical science.

Ms. Tippett: So it’s very interesting that your return to faith was very much connected to finding love.

Mr. Wiman: Yeah, it was.

Ms. Tippett: [laughs] And I’m resisting saying “falling in love,” because we do throw it around so much, and it’s something you fall into and fall out of. But what you have really, really dug into — love as something that puts us in touch with transcendence and with mystery. You were just really aware of that and articulate about it.

Mr. Wiman: Well, I think — it was a revelatory time for me, because I certainly would never have said those things in the past. I had to have the experience to be able to write about it. In fact, I would have actively denigrated the notion, probably.

Ms. Tippett: The notion of …

Mr. Wiman: Oh, the notion that love could open up the world for you in that way. We just published a poem in the magazine by a poet named Spencer Reece, who’s become an Anglican priest, as it happens. And he’s talking about — the whole poem is an elegy for someone he knew, and is trying to get at the truth of his life. And he says, “All I know is that the more he loved me, the more I loved the world.” And I think, in any genuine love — and it’s not simply romantic love…

Ms. Tippett: Right, it’s other loves, yes. It’s our love for our children. It’s friendships.

Mr. Wiman: Right, I think there’s some kind of excess energy. We tend to think of love as closing out the world, and we can only see the face of the beloved, and that everything else goes quiet or goes numb. But actually, what I experienced was that — and I’ve experienced it again with my children — is that the love demanded to be something else. It demanded to be expressed beyond the expression of the participants. It kept demanding more.

And that excess energy, I think, is God. And I think it’s God in us, trying to return to its source. I don’t know how else to understand it. But if I think of myself as having returned to faith — and I do think of that, although I feel like I’m a desperately confused person, and when people look to me for advice or direction on faith, I just feel, sometimes, like it’s hilarious — but I think we have these experiences, and they are — people react against the word “spiritual” these days, but I don’t know what other word to use, at this point — they are spiritual experiences. And then religion comes after that. Religion is everything that we do with these moments of intense spirituality in our lives, whether it’s whatever practice we have; whether it’s going to church; whether it’s how we integrate sacred text into our lives.

Being religious, or taking on some sort of religious elements in your life, you are not necessarily saying, “I agree with everything that this religion says.” What you are saying is that I’ve had these incredible experiences in my life — of suffering or joy, or both, and they have demanded some action of me and demanded some continuity of me. And the only way that I know to do this is to try to find some form in it and to try to share it with other people.

Ms. Tippett: I actually wanted to ask you about the words “faith” and “belief.” You’ve written, “Faith is not a state of mind, but an action in the world, a movement towards the world.”

Mr. Wiman: The way I’ve defined it to myself is, I think of belief as having objects. Faith doesn’t have objects. Faith is an orientation of your life, or it’s an energy of your life, or however you want to define it. But I think it is objectless.

Ms. Tippett: Doesn’t have to be “faith in,” because I think that’s how it gets…

Mr. Wiman: Right, and that has helped me to at least understand those terms somewhat, and to explain to myself why I do need some sort of structures in my life. I do need to go to church. I need specifically religious elements in my life. I find that if I just turn all of my spiritual impulses — if I let them be solitary, as I am comfortable in being — I’m comfortable sitting reading books and trying to pray and meditating. Inevitably, if that energy is not focused outward, it becomes despairing. It turns in on itself, and I will look up in a couple of months, and I find that I’m in despair. And so I think that one of the ways that we know that our spiritual inclinations are valid is that they lead us out of ourselves.

Ms. Tippett: Your story, to me, is very much an example, also, of this phenomenon of our time where we choose these things, where we create our spiritual lives, which is really new. You were given this religious world as a center of gravity in your childhood, which a lot of people were until just a decade or two ago. And then there’s the image I have of you and your fiancée standing outside this church, the day you got engaged.

Mr. Wiman: That’s right, and not going in.

Ms. Tippett: Not going in, but then eventually deciding to go in.

Mr. Wiman: Yeah, I think it’s a perilous difficult situation for people — for everyone — to be left on their own, trying to choose their spiritual lives. [laughs]

Ms. Tippett: To have charge of this. [laughs]

Mr. Wiman: Right, and I think that’s — a lot of mid-century Protestant theology, led by Karl Barth, was a reaction against this: that you can’t simply trust your gut, trust your impulses; that we’ve got to have some way of finding God together. And for him, it was the Bible, and he was very conservative, in certain ways. And I just cannot go there; I cannot follow. I don’t think we can just recovery orthodoxy in that way.

I think — I really feel that a whole new language is being created, and there’s too many people who are struggling with this. Traditional religious language is part of it and will be part of it, but a whole new thing is being created, and it’s going to involve other religions. It’s going to involve other practices. I don’t think you can simply resist it and say, “I’m going to just have my little corner and keep it safe and secure.”

Ms. Tippett: I think a lot about Dietrich Bonhoeffer in prison, before he died, in an extreme situation of having seen the church, in orthodoxy and religious language, be completely co-opted by evil, but saying — starting to talk about “What would religionless Christianity look like?” But also, saying that he thought that even as the language and the ideas might cease to be relevant, that the truths behind them would persist and — kind of what you just said — that new language and new forms would continually be recreated to express those.

Mr. Wiman: Yeah, I often — I love Bonhoeffer, and I’m struck by something else he said that — he said in a letter that he was often more drawn to atheists. He had felt more fellow-feeling with atheists than he did with his fellow believers, and he was trying to understand that in himself. I find Bonhoeffer an incredible figure, because — not simply because he returned to Germany when he could have had a safe life in the United States. He returned, and he felt like if he didn’t share in the destruction of Germany, then he couldn’t credibly participate in its restoration. And he also simply felt that he had a call. We wait and wait and wait for the right thing to do in our lives, but he says, “no, no, no. You’ve got to obey, follow that impulse, even as hazy as it is, and then your faith will come. You don’t get it first. You don’t get it first.” So he lost his life in that. He also said, at one point, “God has called us to be in a world without God.”

Ms. Tippett: Yeah, right.

Mr. Wiman: “Before God and without God, we stand with God.” Some of his statements have the feeling of poetry. They seem so wonderfully suggestive.

Ms. Tippett: Yes, absolutely. So when you said, a minute ago, “We’re developing a new language,” to me, that spiritual clarity and, in fact — well, let’s say Bonhoeffer also was orthodox, certainly.

Mr. Wiman: Yeah, he was, very orthodox.

Ms. Tippett: The spiritual clarity, orthodox clarity, and, for want of a better word, we can call openness to reality, let’s say — I feel like that’s what we’re grasping for now. So when you see, in somebody like Bonhoeffer, those things were not in contradiction, it was —

Mr. Wiman: There is some —

Ms. Tippett: And that’s what you’re describing in yourself.

Mr. Wiman: There is some combination of austerity and clarity that I think we, as a whole culture, are grasping toward. And the main movement of the culture is against it, all the political language; all that is just rot. But I do think there’s this huge cultural grasping toward something that won’t be so froufrou and slip out of our grasp and just make us think it’s ridiculous, and yet, also, something that is open enough to engage those parts of us that we don’t understand.

Ms. Tippett: You’ve written about God — just the word; well, not just the word, the idea — you’ve written about how it’s difficult for modern people. And you talk about existential anxiety, which is something that all the classic philosophers and theologians wrote about, even in the 20th century — Niebuhr — as our essential anxiety that’s at the heart of the human condition. When I’m reading you, I’m thinking, gosh, I don’t think there are lots of people now who are right in the middle of things, writing about this. But actually, what you helped me see is that we do talk about this all the time, but we don’t talk about it in that way. We talk about how our technology is driving us crazy, how we have to create downtime, and how we don’t have space in our lives for what matters. It’s just — the trappings of this existential anxiety are very different, and also, very new.

Mr. Wiman: Yeah, we talk about our —we’ve deflected the soul into questions of the self. There’s a great quote from Fanny Howe, where she talks about “the self has replaced the soul with the fist of survival” — that we’ve created a kind of climate in which, to survive, we all need to hone ourselves. And so we develop and hone ourselves, and we project those selves in all kinds of various ways, whether it’s Facebook or whatever we’re doing. We think of our lives as being successful to the extent that those selves are ratified by other people, and we’ve gotten away from the notion of the soul. It can be a real shock to find somebody who is suddenly talking about those things quite openly.

I am a Christian. I believe that Christ comes alive in communion between people, and I think you — sometimes, I’ll think all kinds of things are wrong with my life. My job is messing me up. My writing is messed up. Something’s messed up. And then I’ll have a conversation with someone about a religious topic, or it’s spiritually informed in some way, and it’s honest. And even if we don’t get anywhere, even if we disagree, the air has been cleared in me, and I realize that, in some ways, that I was dealing with all these things that weren’t the ground, weren’t bedrock. They weren’t the ground of my being, and I’m trying to take care of things — the structures on top instead of the ground of my being. And I find that often, all you need is some kind of conversation with someone, even if it’s just expressing pure anxiety.

Ms. Tippett: Right, which just names that, even if it doesn’t tie it up.

Mr. Wiman: Exactly. Exactly, just names it and shares it — and that it can stabilize you in the world.

Ms. Tippett: And I think that something, also, that modern people will identify with — and the way you talk about faith — is about the animating aspect of doubt in that, even in your prayers; even in the act of going to church. It’s not something separate. It’s not a problem. It’s just part of it.

Mr. Wiman: Well, there’s this other poem — let me read this other poem from the same book, Every Riven Thing. It’s not adjacent to it in the book, but it is, in my mind. It’s called “Hammer Is the Prayer.”

There is no consolation in the thought of God, / he said, slamming another nail

in another house another havoc had half-taken. / Grace is not consciousness, nor is it beyond.

To here with remembrance, to here with heaven, / hammer is the prayer of the poor and the dying.

And as wind in some lordless random comes to rest, / and all the disquieted dust within,

peace came to the hinterlands of our minds, / too remote to know, but peace nonetheless.”

I wrote several poems, after that, like this one, where God is actually expunged from this poem. “There is no consolation in the thought of God,” this poem starts. And I wrote others that — not only did they not credit the idea of Heaven, they actually mocked the notion, actually made fun of it. And I didn’t do this purposefully. The poems got written; they happened to me. And so I sort of looked up in the aftermath of them and thought, “What in the world is going on? Why am I writing these?” And I think it’s very much what you said — that doubt is so woven in with what I think of as faith that it can’t be separated. And I am convinced that the same God that might call me to sing of God at one time might call me, at another, to sing of godlessness. And that sometimes, when I think of all of this energy that’s going on — all of this, what we’ve talked about, these different people trying to find some way of naming and sharing their belief — I think it may be the case that God calls some people to unbelief in order that faith can take new forms.

Ms. Tippett: Let’s go back to the idea that you discovered love at the same time that you discovered faith. In a mature relationship, in love as in faith, the feeling isn’t always there. That initial clarity and intensity is not a constant part of actually being vital and growing. But it’s part of the health of the thing.

Mr. Wiman: Yeah, I think that’s — I hadn’t thought of that, but that’s helpful for me to think of it that way. Yeah, I think that’s…

Ms. Tippett: If we’re grownups about this stuff, if we’re grownups about faith, then…

Mr. Wiman: Then why can’t we all get together and lament the fact that there’s no God? [laughs]

Ms. Tippett: [laughs] Right.

Mr. Wiman: I think — well, the Bible’s actually full of moments like that too.

Ms. Tippett: Yes.

Mr. Wiman: I think that is part of any mature faith, you’re right. But I, like so many people, tend to fall into despair at those moments and think, oh, my God, I don’t believe in anything.

Ms. Tippett: Yeah, well, we fall into those moments of despair in our love relationships as well, right? [laughs]

Mr. Wiman: That’s right, yeah.

Ms. Tippett: I wonder — there’s a lot of language about death in religion and in poetry. And I wonder if some of it feels — how your perspective on that has changed, being, as we’ve said, a person who’s more conscious of his own mortality than most of us. You’ve faced death as, possibly, something in the near term. And death and transcendence, death and beauty, death as a choice, death in discovering what really matters — do you hear that kind of language differently now?

Mr. Wiman: I sure do. I hear that kind of carpe diem language — there’s a famous line from Wallace Stevens: “Death is the mother of beauty,” meaning that we can’t, can’t ever perceive our lives until we look through it through the lens of death, but if you look through the lens of death, then it’s suddenly much more abundant and beautiful and sharp. And I have come to think that that is just a load of crap. [laughs] I think that — I think anyone who could write that line was someone for whom death was an abstraction, and a kind of pleasant abstraction, actually.

As it is, death is an abstraction for all of us. And even if you get, as I have been, close to dying in the last year — even if you get that close, it is still an abstraction; not as much of an abstraction, but you simply cannot imagine your own death, and the mind will not do it. And you can’t quite do it.

I think that we actually have to have the past and the future in any — if you think about it, we have no present. We’re always remembering. There is no actual present. It’s just the way reality is — it takes that long for our brains to process the instant. We’re always remembering events, and we’re always projecting some sort of future, and I think that’s where meaning — that’s how we get meaning in our lives. But I do — I feel, more, that my imagination keeps opening onto these eccentric heavens. And I have to give them credit. I have to give them their due.

Mr. Wiman: I’m much more moved — I think, if you think of someone like Wallace Stevens, he sat back and said, “Death is the mother of beauty; hence from her shall come fulfillment to all our dreams and our desires.” It’s very distant; it’s very detached. It’s a very abstract notion of how we live our lives. I’m much more moved by someone like the Russian poet Osip Mandelstam. And I happen to just have translated a few of his poems. And let me read you this — this is the last poem that Mandelstam wrote. Now Mandelstam was hounded to death by Stalin, and one of the reasons was, he wrote a famous poem that was a mockery of Stalin, which he recited to some friends. And in those days, people could — they were so used to hearing poetry and reciting poetry that they could hear it once and keep it in their heads. And someone memorized the poem from his recitation and then took it to Stalin, and his fate was sealed. So here’s the last day of Mandelstam’s writing life — not the last day of his life; he died in a transit camp not long after this. Picking through garbage was the last anyone saw of him. And he knew what was about to happen to him, and he knew all too well, and he was composing these poems right up until the end. And the last day he died, he wrote either two or three poems, depending on how you put these poems together. But this was one of them.

“And I was alive in the blizzard of the blossoming pear, / Myself I stood in the storm of the bird-cherry tree. / It was all leaflife and starshower unerring, self-shattering power, / And it was all aimed at me.

What is this dire delight flowering fleeing always earth? / What is being? What is truth?

Blossoms rupture and rapture the air, / All hover and hammer, / Time intensified and time intolerable, sweetness raveling rot. / It is now. It is not.”

Now that seems to me an incredible expression of hope and persistence. Seamus Heaney says, somewhere, that hope is a condition of your soul, not a response to the circumstances in which you find yourself. I’m mangling that somehow. But think of Osip Mandelstam writing this, knowing what he was going to, and compare that with Wallace Stevens sitting back and saying, “Death is the mother of beauty.”

Ms. Tippett: Right, right. [laughs] That line you said a minute ago, “the eccentric heavens,” this idea — I also hear that there.

Mr. Wiman: Yeah. These strange sort of ways of surviving seem to keep occurring to me, though if you ask me, Do I believe in heaven? — No, I don’t really believe in heaven in the way that people conceive of it. And yet, it somehow keeps asserting itself in my imagination.

Ms. Tippett: So if I ask you to think about yourself in church all those years ago in west Texas, the church you grew up in, which was just given to you like the air you breathed, and then when you’re in church now, what’s going on that’s different? How is that experience different?

Mr. Wiman: Well, it’s utterly different. I think it’s a weaker experience now. I’m just too conscious. I’m unable to let myself — I wish I were able to let myself go in ways that those people did in my childhood, and still do, when I go to my mother’s church now. It’s one of those big mega-churches, and I don’t agree with their theology, and I don’t like a lot of the ways that they commercialize their services, but it is an incredibly diverse church, and the people are intensely involved with their — they’re treating it as if their whole life were at stake. And the churches I go to, liberal Protestant churches, it seems pretty casual. I wish there were some credible middle ground. I wish there were some way of harnessing that — the intensity that I felt in my childhood — in more sophisticated ways.

Ms. Tippett: That may be another way of describing what — the new language that we talked about that a lot of people now are searching for. It’s not just new language. It’s new forms.

Mr. Wiman: Yeah, and I think art has a big role to play in that — encompassing art. If I think of some of the most intense experiences in my life, they are artistic experiences, and not simply making art, but responding to it. And I think if a church could allow those experiences to happen without necessarily putting them in place and saying they have to be — “They mean this in our liturgy,” or “They represent this”…

Ms. Tippett: Right. I think we’re very self-conscious when people just inject art into worship. That’s the danger there. You’re talking about, I think, part of that.

Mr. Wiman: But I’ve seen it done well. Yes, I’ve seen it done well, where it is just — in fact, I’m just coming from — I was out on Whidbey Island at a conference, and the people there put on — I guess the students did it. They put on a sort of makeshift service, and it was made up of songs that clearly had been written by one of the people there and had just sort of been set to music on the spot; and there was a poem. It was unlike any service that I had been to. They just sort of did one thing after another, which were all addressed to God. And that was the service. And I found it very beautiful, very moving — sort of the perfect thing, for me.

Ms. Tippett: In the preface to Ambition and Survival, this collection of writings, which was — 2007, so it was a few years back — you wrote, “I still believe that a life in poetry demands absolutely everything — including, it has turned out for me, the belief that a life in poetry demands absolutely everything.” Would you tell me what you mean when you say that?

Mr. Wiman: Oh, no. What a paradox. [laughs]

Ms. Tippett: [laughs] It’s five years ago, so maybe it’s not still true. But if it is, what do you mean? I’m trying to wrap my mind around it.

Mr. Wiman: For years, I — there’s a poem I love, by a Canadian poet named Robert Bringhurst, and it starts like this:

“These poems, these poems, / these poems, she said, are poems / with no love in them. These are the poems of a man / who would leave his wife and child because / they made noise in his study, she said. These are the poems / of a man who would murder his mother to claim / the inheritance. These are the poems of a man / like Plato, she said, meaning something I did not / comprehend, but which nevertheless / offended me. These are the poems of a man / who would rather sleep with himself than with women, / she said. These are the poems of a man / with eyes like a drawknife, hands like a pickpocket’s / hands, woven of water and logic / and hunger, with no strand of love in them. These / poems are as heartless as birdsong, as unmeant / as elm leaves, which if they love love only / the wide blue sky and the air and the idea / of elm leaves. Self-love is an ending, she said, / and not a beginning. Love means love / of the thing sung, not of the song or the singing. / These poems, she said… / You are, I said, / beautiful. / That is not love, she said rightly.”

I didn’t mean to quote that whole thing, but for years, I carried that poem like it was a kind of totem in my mind. It was just — it expressed to me, so perfectly, what tensions that I felt between my life as an artist and my life. And I felt that I was giving everything to poetry, and you had to give everything to poetry; and yet, at the same time, I felt some sort of essential energy missing from some of my poems. And I had to eventually give up that notion that you could give your whole life to poetry, that poetry could be this abstract thing that you could devote your life to. I’d made a god. You talk about idolatry, I’d made a god out of it. And I had to have that shattered in order to come to write some of the poems that are in Every Riven Thing. I had to really have that notion tested severely.

Ms. Tippett: I think I’d like to end by having you read at least maybe one of the poems that illustrate what you just said — the place you’ve come to, where that paradox is less agonizing.

Mr. Wiman: So the title is “Every Riven Thing.” And “riven” is kind of an Old Testament word meaning “broken, sundered, torn apart.” This was actually the first poem that I wrote after years of silence, all those years I mentioned. I had gone — I think it was three years without having written a poem. And in the middle of all those dramatic things happening to me, this was one of them. I sat down one day and found myself writing again, and this poem came to me all of a sudden. And it was quite a shock to write a poem, and quite a shock to write a poem, especially, like this one.

“God goes, belonging to every riven thing he’s made / sing his being simply by being / the thing it is: / stone and tree and sky, man who sees and sings and wonders why

God goes. Belonging, to every riven thing he’s made, / means a storm of peace. / Think of the atoms inside the stone. / Think of the man who sits alone / trying to will himself into a stillness where

God goes belonging. To every riven thing he’s made / there is given one shade / shaped exactly to the thing itself: / under the tree a darker tree; / under the man the only man to see

God goes belonging to every riven thing. He’s made / the things that bring him near, / made the mind that makes him go. / A part of what man knows, / apart from what man knows,

God goes belonging to every riven thing he’s made.”

END: see https://onbeing.org/programs/christian-wiman-how-does-one-remember-god-jan2018/#transcript