For Sunday December 11th, 2016

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year A)

Isaiah 35: 1-10

Psalm 146: 5-10

James 5: 7-10

Matthew 11:2-11

The third Sunday of Advent is traditionally called “Gaudete” or “Rejoice” Sunday in the Christian calendar. In many churches, the penitential purple of the season is put aside in favor of a lighter, happier rose, and the week's lectionary readings encourage hopefulness and joy. "The wilderness and the dry land shall be glad, the desert shall rejoice and blossom," promises Isaiah. "Happy are those whose help is the God of Jacob, whose hope is in the Lord their God," declares the Psalmist.

I don’t know about you, but I find these calls to joy difficult. “Rejoice" is a churchy word I don’t use in regular life, so I feel clumsy and hesitant around it. “Joy” itself is a word so overused in America’s commercialization of Christmas, it has become opaque and trivial.

So it's with a mixture of confusion and relief that I wrestle with this Sunday's Gospel reading, which places me in a context quite different from Isaiah's blooming wilderness. Maybe God has an ironic sense of humor, or maybe the lectionary has a wisdom shrewder than I knew. Whatever the case, the Gospel of Matthew has me squatting in a prison cell on this Gaudete Sunday, offering uneasy company to a broken John the Baptist.

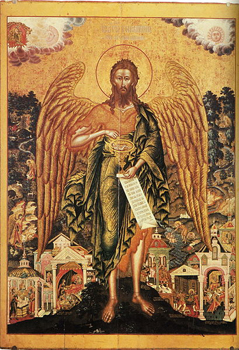

Joy is not evident here behind the bars that hold the fiery Baptizer. Imprisoned for speaking the hard truth to Herod, John is in chains and in crisis, wondering if he has staked his life on the wrong promise and the wrong person. The Messiah, as far as John can tell, has changed nothing. He was supposed to make the world new. He was supposed to bring justice, fairness, and order to human institutions, such that a tyrant like Herod would no longer sit on the throne, and a righteous man like John would no longer languish in a rat-infested prison. Jesus was supposed to finish the costly work John started so boldly in the wilderness — to wield the axe, bring the fire, renew the world.

|

But nothing — nothing at all — has worked out as this disillusioned prisoner thought it would, and all he has left as he paces his cell is an anguished question for the would-be Messiah: Are you the one who is to come, or are we to wait for another?

If you know John's backstory, his crisis of belief might surprise you. After all, this is John the Baptist we're talking about. John, whose very conception occasioned an angelic visit. John, who leapt in his mother's womb at the first glimpse of a pregnant Mary. John, whose fiery preaching drew huge crowds to repentance. John, who saw the heavens open up and the Spirit of God descend like a dove on the newly baptized Jesus.

If we Christians have a uni-directional way of telling our conversion stories — "I journeyed from darkness to light, from ignorance to knowledge, from despair to joy"-- then John's story should stop us in our tracks, because it is an anti-conversion story. By our stock logic, John's journey is a backwards one. From certitude to doubt. From boldness to hesitation. From knowing to unknowing. From heavenly light to jail cell darkness.

Should we call this a case of spiritual failure? Of faithlessness? Of "backsliding?" Jesus doesn't. Instead, he responds to his cousin's pained question with perfect composure, gentleness, and — I would argue — relief. As if to say, "Okay, good. You're willing at last to let go of your preconceptions. You're ready for the saving work of disillusionment. Now you can get to know me — the real me."

"Go and tell John what you hear and see," Jesus tells the disciples who bring him John's question. Tell him that "the blind receive their sight, the lame walk, the lepers are cleansed, the deaf hear, the dead are raised, and the poor have good news brought to them. Blessed is anyone who takes no offense at me."

In other words, Jesus says: go back to John and tell him your stories. Tell him my stories. Tell him what your eyes have seen and your ears have heard. Tell him what only the stories — quiet as they are, scattered as they are, questionable as they are — will reveal. Why? Because who I am is not a pronouncement. Not a sermon, a slogan, or a billboard. Who I am is far more elusive, mysterious, and Other than you have yet imagined. Who I am will emerge in the lives of ordinary people all around you — but only if you'll consent to see and hear.

I wonder what version of Jesus would emerge for me now if I took this invitation to heart. I wonder where and how God would appear if I were more attentive to the stories that usually lie beneath my notice. I wonder how much divine richness I've squandered by mistaking certainty for faith.

| |

There are many places in the Gospels where I wish the writers had given us just one more paragraph, just one more extension of plot and characterization. John's prison is definitely one of those places. How did he respond to Jesus's answer? Did it satisfy him? Did it quell his doubts? Did it renew his joy?

We don't know. All we know is that the liberation Jesus spoke of did not come to John in this earthly life. Yes, the blind saw, and the deaf heard, and the poor received good news. But those joyful stories came to John second-hand; they never became his own. His own story ended in death — a meaningless, grisly death that made a mockery of the divine justice he preached and sought all his life.

If John's untimely death doesn't rattle you, if it doesn't shake your faith even a little bit, then I'd ask you respectfully to pay attention to why. It has always seemed odd to me that Christians who worship the Crucified One have a hard time staying put in the presence of extreme suffering. Somehow, we feel a need to blunt the edges. To soften the blows. To make God okay by making ourselves and each other okay.

But this story is not "okay," and many of our own stories aren't okay either. The prison bars that hold us don't always give way. Our doubts don't always resolve themselves. Justice doesn't always arrive in time. Questions don't always receive the answers we hunger for.

Jesus calls us to see and hear all the stories of the kingdom — and that includes John's story, too. "Blessed is anyone who takes no offense at me," Jesus says. Offense runs away. Offense quits. Offense erects a wall and hides behind it because reality is harsher and more complicated than we expected it would be. Yes, some stories are terrible, period. They break hearts and end badly. People flail and people die, and this, too, is what the life of faith looks like. Don't take offense. Don't flee.

What are we to make of John's story on Gaudete Sunday? Laugh if you will, but John the Baptist is the patron saint of spiritual joy. He was still a fetus when he first leapt at the presence of Mary and Jesus. When it was time for him to “decrease” so that the Messiah could “increase,” he did so willingly, saying, “My joy is now complete.” But as far as we know, his life on this earth ended in darkness and unknowing.

Or maybe it didn't. Maybe John understood something hard and flinty about joy. Joy in a prison cell isn't about sentimentality. Or happiness. Or the pious suppression of our own most painful crises and questions.

|

Maybe he understood that joy is what happens when we dare to believe that our Messiah disillusions us for nothing less than our salvation, stripping away every lofty expectation we cling to, so that we can know God for who he truly is. Maybe he realized that God's work is bigger than the difficult cirumstances of his own life, calling him to a selfless joy for the liberation of others. Maybe John's joy was otherworldly in the most literal sense, because he understood that our stories extend beyond death, and find completion only in the presence of God himself.

"Are you the one who is coming?" John asked in despair.

"You decide," Jesus answered in love.

Silence reigned until John joined the community of saints. But can you hear his answer now? It is filled with joy. YES.

Image credits: (1) Wikipedia.org; (2) Wikipedia.org; and (3) Wikipedia.org.