For Sunday May 20, 2018

Pentecost Sunday

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year B)

Ezekiel 37:1-14

Psalm 104:24-34, 35b

Acts 2:1-21

John 15:26-27; 16:4b-15

At the church I attend, the lectors who read Scripture passages on Sunday mornings always conclude with an invitation. "Hear what the Spirit is saying to God's people,” they say, and everyone responds, “Thanks be to God.”

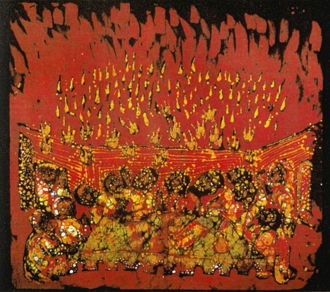

This week, we celebrate Pentecost, the birthday of the Church. From the Greek pentekostos, meaning "fiftieth," Pentecost was a Jewish festival celebrating the spring harvest, and the revelation of the law at Mount Sinai. In the Pentecost story St. Luke tells in this week’s lectionary, the Holy Spirit descended on 120 believers in Jerusalem. The Spirit empowered them to testify to God's great deeds, emboldened the apostle Peter to preach to a bewildered crowd of Jewish skeptics, and drew three thousand converts in one day. It’s a birthday story like no other, full of wild details that challenge the imagination. Tongues of fire. Rushing winds. Accusations of drunkenness. To put it bluntly: God showed up fifty days after Jesus’s resurrection and threw the world a party.

But he did more than that; he gave his followers a clear and startling picture of what Christ’s body on earth should look like. “Hear what the Spirit is saying to God’s people” is an invitation tailor-made for Pentecost. What did the Spirit say on that momentous morning? What did he reveal about God’s dream for the Church?

"All of them were filled with the Holy Spirit,” Luke writes, “and began to speak in other languages, as the Spirit gave them ability." "At this sound the crowd gathered and was bewildered, because each one heard them speaking in the native language of each."

|

Christians often speak of Pentecost as the reversal of Babel, the Old Testament story in which God divided and scattered human communities by multiplying their languages. But in fact, Pentecost didn't reverse Babel; it perfected and blessed it. When the Holy Spirit came, he didn't restore humanity to a common language; he declared all languages holy and equally worthy of God's stories. He wove diversity and inclusiveness into the very fabric of the Church.

Those of us who speak more than one language might be the best equipped to grasp the import of this divine declaration, this miraculous weaving. We understand intuitively that a language holds far more than the sum of its grammar, vocabulary, and syntax. Languages carry the full weight of their respective cultures, histories, psychologies, and spiritualities. To speak one language as opposed to another is to orient oneself differently in the world — to see differently, hear differently, process and punctuate reality differently. There is no such thing as a perfect translation.

If this is true, then what does it mean that the Holy Spirit empowered the first Christians to speak in an unmatched diversity of languages? Was God saying, in effect, that his Church, from its very inception, needed to honor the boundless variety and creativity of human voices? That he was calling it to proclaim the great deeds of God in every tongue — not because multiculturalism is progressive and fashionable, or because the Church is a "politically correct" institution — but because God's deeds themselves demand such diverse tellings? Could it be that there is no single language on earth that can capture the deeds of God?

Here's a detail I cherish about the Pentecost story: when the disciples and their friends began to speak in foreign languages, the crowds gathered outside their meeting place understood them. And this — the fact of their comprehension — was what confused them. They were not confused by the message itself; the message came through with perfect clarity in their respective languages.

|

What the crowds found baffling was that God would condescend to speak to them in their own mother-tongues. That he would welcome them so intimately, with words and expressions hearkening back to their birthplaces, their childhoods, their beloved cities, countries, and cultures of origin. As if to say, "This Spirit-drenched place, this fledging church, this new Body of Christ, is yours. You don't have to feel like outsiders here; we speak your language, too. Come in. Come in and feel at home."

As Christians, we place great stock in language. In words. Like our Jewish and Muslim brothers and sisters, we are People of the Book. We love the creation stories of Genesis, in which God births the very cosmos into existence by speaking: "And God said." "In the beginning was the Word," we read in John's dazzling poem about the Incarnate Christ. On Sunday mornings, we profess our faith in the languages of liturgy, creed, prayer, and music. In short, we believe that language has power. Words make worlds. And unmake them, too.

To attempt one language as opposed to another is to make oneself a learner, a servant, a supplicant. To speak across barriers of race, ethnicity, gender, religion, culture, denomination, or politics is to challenge stereotype and risk ridicule. It is a brave and disorienting act. How often do we engage in it in our churches?

Whether we like it or not, this is what the Holy Spirit required of Christ's frightened disciples on the birthday of the Church. Essentially, to stop huddling in their version of sameness and safety. To throw open their windows and doors. To feel the pressure of God's hand against their backs, pour themselves into the streets, and speak. When the Holy Spirit came, silence was no longer possible; they were on fire.

|

In the end, the Pentecost story required surrender on both sides. Those who spoke had to brave languages outside of their comfort zones. They had to risk vulnerability in the face of difference, and do so with no guarantee of welcome. They had to trust that no matter how awkward, inadequate, or silly they felt, the words bubbling up inside of them — new words, strange words, scary words — were nevertheless essential words — words precisely ordained for the time and place they occupied.

Meanwhile, the crowds who listened had to take risks as well. They had to suspend disbelief, drop their cherished defenses, and opt for wonder instead of contempt. They had to widen their circles, and welcome strangers with odd accents into their midst. Not all of them managed it — some sneered because they couldn't bear to be bewildered, to have their neat categories of belonging and exclusion explode in their faces. Instead, like their ancestors at Babel, who scattered at the first sign of difference, they retreated into the well-worn narrative of denial: "Nothing new is happening here. This isn't God. These are blubbering idiots who've had too much to drink."

But even in that atmosphere of suspicion and cynicism, some people spoke, and some people listened, and into those astonishing exchanges, God breathed fresh life.

Something happens when we speak each other's languages — be they cultural, political, racial or liturgical. We experience the limits of our own perspectives. We learn curiosity. We discover that God's "great deeds" are far too nuanced for a single tongue, a single fluency.

|

What is the Spirit saying to God’s people? Maybe that we live in a world where words have become toxic, where the languages of our cherished "isms" threaten to divide and destroy us? That the troubles of our day -- global, civilizational, catastrophic — cry out for the balm of a bold and creative Church willing to engage across barriers? That if we don't learn the art of speaking each other’s languages, we’ll burn ourselves down to ash?

It is no small thing that the Holy Spirit loosened tongues on the birthday of the Church. In the face of difference, God compelled his people to engage. From Day One, the call was to press in, linger, listen, and speak.

Because here's the thing: no matter how passionately I disagree with your opinions and beliefs, I cannot disagree with your experience. Once I have learned to hear and speak your story in the words that matter most to you, then I have stakes I never had before. I can no longer flourish at your expense. I can no longer abandon you.

Can we hear what the Spirit is saying to us, his people? God is doing something new. We can be a part of it. We can be on fire for the healing of the world. Thanks be to God.

Image credits: (1–4) Art & Theology.