For Sunday July 29, 2018

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year B)

2 Kings 4:42-44

Psalm 145:10-18

Ephesians 3:14-21

John 6:1-21

I grew up with parents who were always feeding people. I can barely remember a weekend when we didn’t have people — parishioners, college students, relatives, neighbors — sitting around our dining table at dinnertime. In fact, my earliest memories all involve warm, bustling kitchens, tables laden with food, and countless guests enjoying food and fellowship. My mom garnishing fragrant pans of lamb biryani with cashews and raisins for a crowded church potluck. My dad presiding over hamburgers, hot dogs, and tandoori chicken at our annual Sunday School barbecue. Waking up to the fragrance of onion-ginger-garlic (India’s culinary “trinity”) frying on our stove as my mom and my aunts prepared a traditional Easter breakfast for our extended family.

Of course, as a child, I had no concept of how much time, effort, and commitment went into my parents’ lifestyle of hospitality. Neither did I understand that my parents valued feeding people so much because they knew firsthand what it felt like to go hungry. Only as a teenager did I learn that each of them remembered lean times back in India, times when drought, recession, or failed crops rendered food scarce. My father, in particular, had vivid memories of going to bed hungry as a little boy. As I came to appreciate later, it was my parents’ own, acute awareness of hunger — of what it feels like to need and not get — that motivated them to extend an open table to others.

This week, our lectionary reading centers around Jesus's multiplication of the loaves and fishes — the only Jesus story that appears six times across the four gospels. Clearly, this event meant a lot to the early church. But what can it mean to us, here, now, in the 21stcentury?

|

In its original setting, I can easily imagine how Jesus' actions would have resonated with the crowds who flocked around him. They were colonized peasants. Overworked, underpaid, and malnourished. They knew the agony of an empty table. The agony of watching their children cry for bread.

But me? Not so much. I've never been hungry like that. I've never had to wait more than a few hours for a meal. So where is the resonance — the challenge, the indictment, the power — of this miracle for me?

When I was little, my parents, brother, and I often spent our summers in the villages my parents grew up in, back in rural South India. There, too, food was central. I still remember how my grandmother chased down poultry, haggled with the fish-sellers, sent a farm-hand up a tree to cut down coconuts, gathered peppers and green beans from her garden, and hand-ground spices on a slab of stone in the backyard to make the mouth-watering curries she took such pleasure in feeding us.

In that world, food was a gift. To prepare it with care was an act of generosity and deep love. To receive it with gratitude was a matter of honor and respect. As my mother constantly reminded me when we had to visit several relatives in one afternoon, and every last one of them insisted on stuffing treats into my mouth: "Eat something. At least a bite. There's no worse insult you could offer than to refuse their food."

In contemporary Western culture, though, it's much harder to honor food as a gift. We tend to treat it like dynamite. Often, we carry our beautiful hors d'oeuvres to our church potlucks, circle the laden tables with fear in our eyes, nibble a little here and a little there — always afraid of who might be watching — and then carry our beautiful, barely-touched dishes home again.

|

I'm not judging anyone; I think we've come by the problem honestly. Jesus' feeding miracles were intended to speak abundance into a culture of scarcity. But we live in a culture of excess. Excess messaging, packaging, consuming, and dieting. We hardly know how to hear the word "abundance" in a positive light; we're too scared of its dangers to trust in its promise. For some of us, food is an idol. For others, an enemy. For still others, an addiction coated in secrecy and self-loathing.

How would we respond if Jesus performed a loaves-and-fishes miracle now, in our contemporary midst? Would we allow ourselves to enjoy his generosity? Savor his offering? Or would we hem and haw and hesitate? St. Mark’s version of this miracle says that the crowds “ate and were satisfied.” Would we be able to say that? Or would we say something more like:

"We ate, and looked around to see if we’d eaten more or less than the people sitting next to us.”

"We ate, and immediately started calculating: 700 calories? 900? How long on the treadmill to undo this damage?”

"We ate, but only the fish, not the bread. You know. Carbs."

"We didn’t eat. We gorged."

When Jesus fed the multitudes, people sat down together, taking only what they needed so that everyone got enough. The point was not to scheme, conserve, or quantify. The point was not to clamor for more. The point, very simply, was to enjoy the gift of a single day's portion in the company of others. Abundance didn't have to lead to gluttony. Food didn't have to lead to fear, isolation, and shame.

But when Jesus fed the multitudes, he was also acknowleding what we so often try to forget: that we are physical beings, with legitimate physical needs. We're not airy spirits; we have bodies, and those bodies themselves are gifts from God. Gifts worthy of honor and care.

In fact, I would argue that Jesus was able to perform the miracle he did precisely because he took basic human need so seriously. When his disciples looked at the crowds, they saw only their own insufficiency. Their own scant resources. The impossibility of the situation.

|

But Jesus allowed himself to see genuine need, and he allowed that need to hit him squarely in his own gut. In the face of the crowd’s deep hunger, despair couldn’t be an option; someone had to act. Maybe it’s only when we get in touch with our own deepest needs — for nourishment, for companionship, for help, for love — that we can extend a generous table to others. Maybe we need to be felled by our own hungers before we can turn abstract compassion into life-saving action.

The crowds ate and were satisfied. Is this because they ate in the presence of Jesus? What would that be like? To invite him to our tables? To let him watch and partake as we eat? To welcome the Incarnate Jesus into the intimate realm of our bodily hungers? Where might such brave communion lead?

In the end, Jesus' feeding miracles were his self-revelations. He gave bread because he is Bread. He fed hungry bodies because he, too, inhabited and honored a body.

At my church, we say this prayer during Eucharist. May it be ours this week and always: Lord, be known to us. In our own bodies, which are your temple. In the giving and receiving of good gifts. In the breaking of the bread.

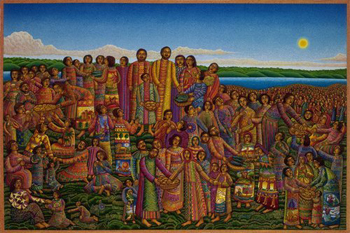

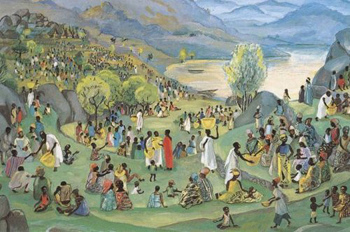

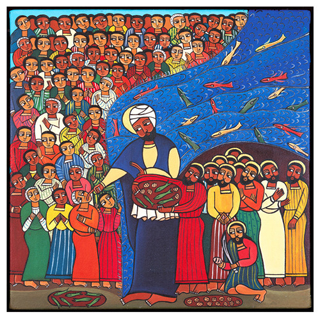

Image credits: (1–3) Global Christian Worship.