For Sunday August 5, 2018

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

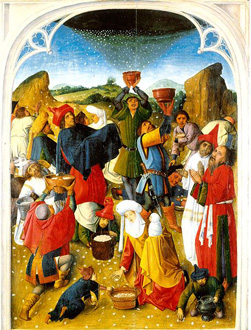

Exodus 16:2-4, 9-15

Psalm 78: 23-29

Ephesians 4:1-16

John 6:24-35

Am I hungry? If yes, what am I hungry for? If no, what has made me full? These are some of the questions I’ve been wrestling with as I linger over this week’s Gospel reading. Here are others: Am I ashamed of my hunger? Does fullness scare me? What kinds of bread do I substitute for Jesus?

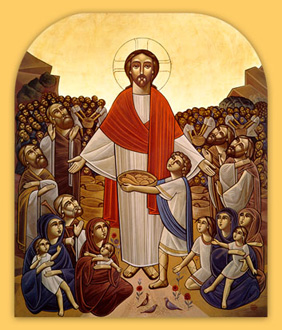

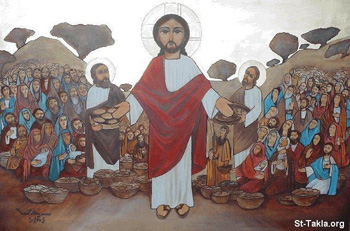

Every three years, the lectionary invites us — or forces us! — to spend five long weeks in John’s Gospel, contemplating Jesus’s self-description as “the bread of life,” or “the bread which comes down from heaven.” It’s a daunting business, to stay with one metaphor for so long. After all, bread is bread, right? What earthly thing could be more basic and simple? As far as its spiritual implications go, we know that Jesus fed the multitudes, we believe he’s mysteriously present at the Communion table, and we generally agree that Christians should donate to food banks or volunteer in soup kitchens. What else is there to understand?

Nothing. Because understanding is not the issue. At least not for me. Not anymore.

Growing up, I was taught that being a Christian meant understanding and believing the right things. To accept Jesus, to be "born again," was to affirm a set of doctrines about who Jesus is and what he accomplished through his death and resurrection. To enter into orthodox faith was to agree that certain theological abstractions about God, Jesus, the Holy Spirit, the human condition, the Bible, and the Church, were true.

But this way of doing Christianity — this way of defining faith as an intellectual assent to precisely codified doctrines — has fallen apart for me. Not because I can't assent, but because my assenting, in and of itself, has not fostered anything close to the communion I desire to have with God. If anything, intellectual assent has become a smokescreen and a stumbling block. Comprehension hasn’t sated my hunger.

|

But neither has the “progressive” perspective I’ve been introduced to more recently, in which Jesus is little more than a wisdom teacher or moral exemplar. Jesus is a wisdom teacher and a moral exemplar, no doubt. He taught with deep insight and authority, and the compassionate life he lived is more than worthy of our emulation. But there’s a problem with reducing Jesus to a clever guru or Generic Good Guy — a problem Jesus articulates very carefully in the lectionary readings we’re lingering over this summer. He doesn’t stop at telling the crowds to “Believe in me,” “Learn from me,” or even “Follow me.” He doesn’t bother with, “Understand me,” either. Jesus says something far more intimate and provocative when he calls himself our bread. He says, “Eat me.” Eat me, and never be hungry again.

What’s at stake for me in this strange invitation is whether or not I will move past religion and into intimacy. Past abstraction and into communion. Past self-sufficiency and into radical, whole-life dependence on a God I can taste but never control. We become what we eat, after all. So what am I becoming?

In her beautiful meditation on Jesus as bread, theologian and Episcopal priest, Lauren Winner writes: “In calling himself ‘the bread of life,’ — and not, say, crème caramel or caviar — Jesus is identifying with basic food, with sustenance, with the food that, for centuries afterward, would figure in the protest efforts of poor and marginalized people. No one holds caviar riots; people riot for bread. So to speak of God as bread is to speak of God’s most elemental provision for us.”

Which brings me back to my original question. Am I hungry? Am I hungry for God? Do I feel in my gut that Jesus is “elemental provision?” Not appetizer, not dessert, not occasional-dietary-supplement, but essential, everyday food without which I will starve and die?

In this week’s lectionary reading, Jesus invites the crowds to recognize the hungers beneath their hungers. Of course they’re hungry for literal bread; they’re poor, food is scarce, and they need to feed themselves and their families. There’s nothing wrong, substandard, or “unspiritual” about their physical hunger — remember, Jesus tends to their bodily needs first, without reservation or pre-conditions. But he doesn’t stop there. Instead, he asks the crowds to probe the deeper soul hungers that drive them restlessly into his presence — hungers that only the “bread of heaven” can satisfy.

|

What are those hungers? I can only answer for myself, so here’s my list: a hunger for meaning and purpose. A longing for connection, communion, intimacy, and love. A desire to know and to be known, deeply and authentically. A hunger for delight, for joy, and for creative engagement with the world in all its complexity, mystery, and beauty. And an ongoing need for healing, wholeness, and steady courage in the face of fear.

That’s my list, today and right now. What’s yours?

Of course, it’s one thing to name our hungers, but quite another to trust that Jesus will satisfy them. After all, we’re so good at finding substitutes for communion with God. Mine include perpetual busyness, social media, books, movies, the 24-hour-news-cycle, exercise, chocolate, and other people. Do I really trust that Jesus is my bread? My essential sustenance? Very often, the answer is no. Very often, Jesus is an abstraction. A creed. A set of Sunday rituals I consider pleasant but optional. Why? Because I don’t come to him ravenous. I don’t recognize my daily, hourly dependence on his generosity. In short, I just plain don’t expect to be fed by him. Instead, I hide my hunger, because I'm ashamed to want and need too much.

In a powerful sermon on God’s generosity, Lutheran minister Nadia Bolz Weber describes the shame that often keeps us from feasting on Jesus: “It’s hard to accept not just that God welcomes all, but that God welcomes all of me, all of you. Even that within us we wish to hide: the part that cursed at our children this week, or drank alone, or has a problem with lying, or hates our body. That part within us that suffers from depression and can’t admit it, or is too fearful to give our money away, or is riddled with shame over our sexuality, or cheats on taxes. All these parts of us we wish Jesus had the good sense to not welcome to his table are invited to taste and see that the Lord is good."

|

I write tentatively this week, because I’m such a novice in the presence of this challenging lection on hunger, bread, and Jesus. I want to “taste and see that the Lord is good.” I long to feast on the bread that comes from heaven. But I recognize too well the shame and hesitation that Bolz-Weber describes.

So where should I — or we — go from here? Once we’ve named and probed our hungers, once we’ve moved an inch closer to trusting God with the scariest desires of our hearts, where do we head next? Into contemplation, I think. Into silence, openness, and deep vulnerability. Into a willingness to truly “eat” Jesus — to take him into ourselves day after day after day, through whatever spiritual practices work best for us. Prayer? Meditation? Lectio Divina? Song? Jesus wants to be so much more than a creed, a good example, or a teacher in our lives. He wants to be food. He is food. Are we hungry for him? Will we allow his substance to become ours? The bread of heaven is ours for the tasting.

May we absorb it. May we share it. May we desire it above all things. May its nourishment permeate us through and through until we, like Jesus, become life-saving bread for the whole world.

Image credits: (1) Wikimedia.org; (2) St-Takla.org; and (3) Wikimedia.org.