For Sunday November 11, 2018

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year B)

1 Kings 17:8-16

Psalm 146

Hebrews 9:24-28

Mark 12:38-44

"The Widow's Mite" is a classic Gospel story — a go-to narrative for Stewardship Season. Who hasn't heard the moving account of the widow who slips quietly into the Temple, drops her meager offering into the treasury, and slips away? Who hasn't squirmed when a well-meaning pastor brings the story to its inevitable, “How then shall we live?” conclusion: "If a desperately poor widow can give her sacrificial bit, how much more should we — so comfortably wealthy by comparison — give out of our abundance to further the Lord’s work?

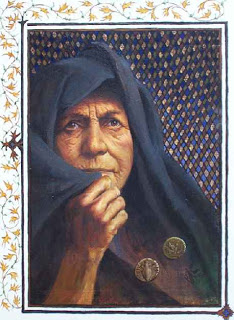

I'll admit it; I've squirmed, but not so much because the question indicts my giving. I've squirmed because this woman's brief appearance in Mark’s Gospel haunts me; her story is sharp-edged and troubling. Something in me doesn't want her reduced to a moral, or exploited for the sake of capital campaigns and annual budgets. Something in me feels indignant. I wish I knew her name. I wish I knew for sure that her real-life fierceness exceeded the piety we've imposed on her. I hope — I hope — she died in peace.

Died? Yes. Died. She died, probably mere days after she dropped those two coins into the Temple treasury. In case that's a surprise, consider again what Jesus said about her as she left the Temple that day: "She out of her poverty has put in everything she had, all she had to live on." The Greek word behind “all she had to live on” is bios (from which we derive “biology.”) It means “life.” In other words, the widow sacrificed her whole life.

|

As far as I can tell from reading the Gospels, Jesus wasn't given to exaggeration. If he says the woman gave everything she had, well, she gave everything she had. We know she was a widow in first century Palestine, a woman living on the margins of her society. She had no safety net. No husband to advocate for her, no pension to draw from, no social status to hide behind. She was impoverished and vulnerable in every single way that mattered. Two pennies short of the end. If I'm getting the timing right, Jesus died four days after the events in this story. I wonder if the widow did, too.

So here's why I'm troubled by this Gospel reading: what does it mean to applaud a destitute woman who gave her last two cents to the Temple, before slipping away to starve? Is this really a story of selflessness? Or is it a cautionary tale about naivete? Should we cheer, weep, or complicate the story further?

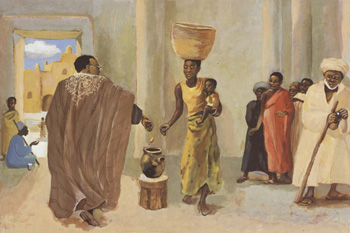

St. Mark prefaces the widow's offering with an account of Jesus blasting the religious leaders of his day for their greed, pomposity, and crass exploitation of the poor. "Beware of the scribes," Jesus tells his followers. "They devour widow's houses and for the sake of appearance say long prayers." Their piety, in other words, is a sham, and the religious institution they govern is corrupt — not in any way reflective of the God the Psalmist calls a "Father of orphans and protector of widows."

|

Indeed, in the days leading up to the widow's last gift, Jesus offers one scathing critique after another of the economic and political exploitation he witnesses around him. He makes a mockery of Roman pomp and circumstance when he processes into Jerusalem on a donkey's back. He cleanses the Temple's money-mongering with a whip. He refuses to answer the chief priests, scribes, and elders when they demand to know the source of his authority. He confounds religious leaders on taxes, indicts them with a scathing parable about a vineyard and a murdered son, defeats them on the question of resurrection, and bewilders them with riddles about his Davidic ancestry.

So why on earth would he turn around and praise a woman for endangering her already tenuous life to support an institution he considers corrupt?

The simple answer is, he doesn't. Read the story carefully; he doesn't. Centuries of stewardship sermons notwithstanding, Jesus never commends the widow, applauds her self-sacrifice, or invites us to follow in her footsteps. He simply notices her, and tells his disciples to notice her, too.

This is a moment in the story when I'd give anything to hear Jesus's tone of voice, and to see the expression on his face. Is he heartbroken as he tells his disciples to peel their eyes away from the rich folks and glance in her direction instead? Is he outraged? Is he resigned? Does he tell one of his friends to run after the woman and give her a bit of bread, or at least a drink of water? What does it mean to Jesus, mere seconds after he's described the Temple leaders as devourers of widows' houses, to witness just such a widow being devoured? And worse, participating in her own devouring?

|

Here's a telling postlude: immediately after the widow leaves the Temple, Jesus leaves, too, and as he does, an awed disciple invites Jesus to admire the Temple's mammoth stones and impressive buildings. Jesus's response is quick and cutting: "Not one of these stones will be left upon another; all will be thrown down."

Ouch. I wonder if the widow is still on Jesus's mind as he predicts the destruction of the Temple. He has just watched a trusting woman give her all to an indefensible institution, one that refuses to protect the poor. No edifice steeped in such injustice will stand.

Back to my earlier question: should we cheer or weep in the face of this story? Or — here's a third alternative — should we call out (as Jesus did) any form of religiosity that manipulates the vulnerable into self-harm and self-destruction? Any form of piety that privileges long-winded prayers over works of compassion and liberation? Any version of Christianity that valorizes soul-killing suffering as redemptive? Any practice of faith that coddles us into apathy in the face of economic, racial, sexual, and political injustice?

Jesus notices the widow. He sees what everyone else is too busy, too grand, too spiritual, and too self-absorbed to see. For me, this is the only redemptive part of the story — that Jesus's eyes are ever on the small, the insignificant, the unloved, and the hidden.

What did Jesus notice? I don't know for sure, but I'll hazard some guesses.

|

I think he noticed the widow's courage. I imagine it took quite a bit of courage for her to make her “insignificant” gift alongside the rich with their fistfuls of coins. Even more to allow the last scraps of her security to fall out of her palms. And more still to swallow panic, desperation, and the entirely human desire to cling to life no matter what — and face her end with hope.

I think Jesus noticed her dignity. Surely she had to steel herself when widowhood rendered her worthless — a person marked "expendable" even by the Temple she loved. Surely she had to trust — in the face of all the evidence piled up around her — that her tiny gift had value in God's eyes. In her astonishing generosity, Jesus recognized a kind of power: those two coins were her gestures of defiance. They marked her subversive resistance to dehumanization.

And finally, I think Jesus noticed her vocation. Whether she knew it or not, the widow's action in the Temple that day was prophetic. She was a prophet in the sense that her costly offering amounted to a holy denunciation of injustice and corruption. Without speaking a word, she spoke God's Word in the ancient tradition of Isaiah, Elijah, Jeremiah, and other Old Testament prophets.

But she was also prophetic in the Messianic sense, because her self-sacrifice prefigured Jesus's. She, too, gave up her life in the face of the unjust system that exploited her. Perhaps what Jesus noticed was kinship. Her story mirroring his. The widow gave everything she had to serve a world so broken, it killed her. Days later, Jesus gave everything he had to redeem, restore, and renew that world.

Image credits: (1) The Good Heart; (2) Fr. Alexis Luzi, OFM, Cap.; (3) Katie Hoffman Fine Art; and (4) RevGalBlogPals; ~creating community for clergywomen~.