For Sunday March 24, 2019

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

Isaiah 55:1-9

Psalm 63:1-8

1 Corinthians 10:1-13

Luke 13:1-9

In his beautiful book of narrative theology, In the Shelter: Finding Welcome in the Here and Now, poet and healer Pádraig Ó Tuama describes the Buddhist concept of “mu,”or un-asking. If someone asks a question that’s too small, too flat, too confining, Ó Tuama writes, you can answer with this word mu, which means, “Un-ask the question, because there’s a better question to be asked.” A wiser question, a deeper question, a truer question. A question that expands possibility, and resists fear.

If I could sum up this week’s Gospel reading in a single word, I would adopt Ó Tuama’s. Mu. As St. Luke describes the scene, some folks come to Jesus with headline news of horror and tragedy. Pontius Pilate has slaughtered a group of Galilean Jews, and mingled their blood with the blood of sacrifical lambs. Meanwhile, the tower of Siloam has collapsed, crushing and killing eighteen people. The reporters accompany these brutal accounts with a question as old as the human race: why? Why did these terrible things happen? Why is there so much pain in the world? Why does a good God allow human suffering?

Jesus’s response? Mu. Ask a better question.

For two thousand years, questions of theodicy have plagued Christianity, and for two thousand years, we Christians have failed to find answers that satisfy us. Yet we can’t stop asking the questions. We still crave a Theory of Everything when bad stuff happens. We still look for formulas to eradicate the mystery. Everything in us still longs to make sense of the senseless.

As Luke’s Gospel makes clear, the people who ask Jesus their versions of the “why?” question already have an answer in mind. They don’t approach Jesus blank slate; they show up hoping to confirm what they already believe. That is, they come expecting Jesus to verify their deeply held assumption that people suffer because they’re sinful. That folks get what they deserve. That bad things happen to bad people.

|

It’s tempting for us 21st century Christians to look at such beliefs and feel smugly superior in comparison. But how different, really, are the beliefs we hold about human suffering? When the unspeakable happens, what default settings do we revert to? “Nothing happens outside of God’s perfect plan.” “God is testing and refining your character though this tragedy.” “This is the refiner’s fire.” “The Lord never gives anyone more than they can bear.” “Buck up — other people have it worse.” “This vale of tears is not your true home; everything will be restored in eternity.”

The problem with every one of these answers is that they hold us apart from those who suffer. They innoculate us from the searing work of solidarity, empathy, and compassion. They keep us from embracing our common lot, our common brokenness, our common humanity. When Jesus challenges his listeners’ assumptions and tells them to repent before it’s too late, I think part of what he’s saying is this: any question that allows us to keep a sanitized distance from the mystery and reality of another person’s pain is a question we need to un-ask. “Mu,” Jesus says to the folks who bring him the news about Pilate and Siloam. “Mu,” he says to us when we wax eloquent about “them” and “us.” Their sinfulness and our piety. Their conservative backwardness and our progressive sophistication. Mu. You’re asking the wrong questions. You’re mired in irrelevance. You’re losing your life in your effort to save it. Start over again. Ask a better question. Go deep. Be brave.

Okay. But what is the better question? If asking “why?” won’t get us anywhere, what kind of question will? In typical fashion, Jesus addresses the problem with a story. A landowner had a fig tree planted in his vineyard, Jesus tells his listeners. One day, the landowner went looking for fruit on the tree, and found none. Incensed, he confronted his gardener: “For three years I have come looking for fruit on this fig tree,” he said, “and still I find none. Cut it down! Why should it waste the soil?” But the gardener begged his employer for more time: “Sir, let the tree alone for one more year, until I dig around it and put manure on it. If it bears fruit next year, well and good; but if not, you can cut it down.”

|

What an odd story to tell at such a moment! What on earth does a fruitless fig tree have to do with Pilate’s heinous killing spree, or with the massive technological failure that toppled the tower of Siloam? What is Jesus saying?

Well, for starters, he’s saying, “Engage in story rather than platitude.” Platitudes are flat. Formulas are reductive. Theories don’t heal. And questions that call for shallow answers aren’t worth asking in the face of tragedy. But stories? Stories open up possibility. Stories include, unmake, and transform us. Why did those Galilean Jews die? Why did the tower fall? Okay, sit down, let me tell you about a fig tree…

The parable Jesus tells invites questions in several directions at once. I can’t possibly exhaust them — none of us can — but here are a few to get us started:

In what ways am I like the absentee landowner, standing apart from where life and death actually happen? How am I refusing to get my hands dirty? Wallowing in futility and despair? Pronouncing judgments I have no right to pronounce? Am I prone to look for waste, loss, and scarcity in the world — or for potential and possibility? Where in my life — or in the lives of others — have I prematurely called it quits, saying, “There’s no life here worth cultivating. Cut it down.”

In what ways am I like the fig tree? Un-enlivened? Un-nourished? Unable or unwilling to nourish others? In what ways do I feel helpless or hopeless? Ignored or dismissed? What kinds of tending would it take to bring me back to life? Am I willing to receive such intimate, consequential care? Will I consent to change? Might I dare to flourish in a world where I have thus far been invisible?

In what ways am I like the gardener? Where in my life am I willing to accept Jesus’s invitation to go elbow-deep into the muck and manure? Where do I see life where others see death? How willing am I to pour hope into a project I can't control? Am I brave enough to sacrifice time, effort, love, and hope into this tree — this relationship, this cause, this tragedy, this injustice — with no guarantee of a fruitful outcome? Can I, in the words of Bishop Ken Untener, be the prophet of a future not my own?

|

I won’t lie: I’m a pro at asking the why question. “Why?” is the question I stick in God’s face whenever bad stuff happens; I ask it more often than all other questions combined. I ask because I want to understand. I ask because I’m afraid. I ask because mystery unnerves me.

And yet, every time I ask why, Jesus says “mu.” He says it because “why” is just plain not a life-giving question. Why hasn’t the fig tree produced fruit yet? Um, here’s the manure, and here’s a spade — get to work. Why do terrible, painful, completely unfair things happen in this world? Um, go weep with someone who’s weeping. Go fight for the justice you long to see. Go confront evil where it needs confronting. Go learn the art of patient, hope-filled tending. Go cultivate beautiful things. Go look your own sin in the eye and repent of it while you can.

In short: imagine a deeper story. Ask a better question. Live a better answer. Do it now. Why? Because there is no “us” and “them.” Because there are no guarantees. Because all of us are beloved, all of us are perishing, and all of us need the care of a hopeful, patient gardener. Ask a better question. Do it now.

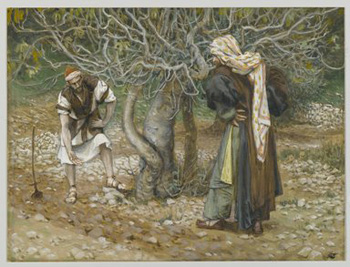

Notes on Art:

- “The Vine Dresser and the Fig Tree” by James Tissot (1836-1902)

- Unknown

- Unknown

Image credits: (1) BrooklynMuseum.org; (2) Vridar.org; and (3) Wordpress.com.