Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year B)

1st Samuel 17: 1a, 4-11, 19-23, 32-49

Psalm 9:9-20

2 Corinthians 6:1-13

Mark 4:35-41

In his 1993 book, Wishful Thinking: A Seeker's ABC, Frederick Buechner offers this advice about Scripture: "Don't start looking in the Bible for the answers it gives. Start by listening for the questions it asks."

Here are some questions the Bible asks — questions which speak powerfully to the wisdom of Buechner's advice:

"Where are you? (Genesis 3:9)

"Am I my brother's keeper?" (Genesis 4:9)

"My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?" (Psalm 22:1)

"Who is my neighbor" (Luke 10:29)

"What did you go out into the desert to see?" (Matthew 11:8)

"How many loaves do you have?" (Matthew 15:34)

"What are you looking for?" (John 1:38)

"Do you want to get well?" (John 5:6)

"What is truth?" (John 18:38)

Buechner goes on to say this: "When you hear the question that is your question, then you have already begun to hear much. Whether you can accept the Bible's answer or not, you have reached the point where at least you can begin to hear it, too."

|

|

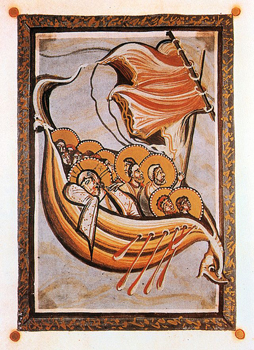

Calming the Storm — Hitda Codex, after 1000.

|

I'm particularly grateful for Buechner's advice right now, because the Gospel reading for this week is difficult for me, and my efforts to read it for "the answers" have been frustrating. Luckily, the reading is chock full of questions, and those questions resonate powerfully in my mind and heart.

The lectionary reading is from the Gospel of Mark, and the miracle it describes — Jesus' calming of the sea — is one of the most dramatic and beloved ones in the New Testament. The setting is the Sea of Galilee, a body of water 680 feet below sea level, surrounded by hills, and prone to sudden, violent windstorms.

The time is evening. After a long day spent preaching to the multitudes, Jesus is curled up in the stern of a boat — his head on a cushion — and sleeping soundly as his disciples steer the vessel to the other side. All at once, the winds pick up, the waves grow huge, and the boat threatens to capsize. Though many of the disciples are seasoned fishermen, they realize quickly that their efforts to bail water from the boat and save their wind-whipped sails are futile; the storm is far too powerful.

In desperation, they rouse the still-sleeping Jesus. Not with a gentle plea for help, but with a question so full of bewilderment, accusation, and panic, I feel its bite across the centuries: "Teacher, don't you care that we are drowning?"

Boom. Question One. "Don't you care that we are drowning?"

I know this question; I know it far too intimately to judge the disciples for asking it. Some Christians, I'm sure, come easily to the belief that Jesus cares for them. Others, for various reasons, do not. Some of us have been wounded by bad religion. Others have suffered forms of abuse — emotional, physical, sexual — that make it very hard to trust in anyone's goodness, even God's. Others have cried out for help in the midst of life's catastrophic storms, and experienced a sleeping Jesus.

Intellectually, I know that the answer to the question is always yes. Yes, our Teacher cares when we are drowning. But as the saying goes, the greatest distance on earth is the distance between our minds and our hearts. For me, the question is a dynamic one — I have to keep living it, asking it, facing it. I can't grab hold of the answer and then put it away; I have to hold it before my eyes day after day. For me, the "yes" of God remains a promise to grow into.

The next two questions in the story come from Jesus. He asks them after he wakes up, rebukes the wind, and stills the sea. In the deep calm after the storm, he turns to face his now-even-more-bewildered disciples. "Why are you afraid?" he asks. "Do you still have no faith?"

"Why are you afraid?" Well, duh. Is Jesus kidding?

When I was twelve years old, my little brother, two older cousins, and I snuck off to play by a river near my father's ancestral home in South India. If our parents had guessed what we were up to, they would have hit the roof; it was monsoon season, and the river was swollen, fast-moving, and treacherous.

We didn't intend to play in the river. But in the predictable way that kids' adventures go awry, one dare turned into another, and soon we were knee-deep, waist-deep, chest-deep in the churning water. I can't remember who lost their footing first. But soon enough, three of us were in serious trouble, pulled under the current, unable to swim, and drowning. One cousin — the eldest among us — was left with the ghastly responsibility of attempting three rescues.

To this day, we don't know how he did it. I do know that for long moments, I experienced the terror of near-drowning — struggling for air, gulping water, choking, and contemplating the possibility that I was about to die a painful death. Afterwards, the cousin who saved us said that if he had failed, he would have jumped right back into the river and taken his life — better that than go home to face our families.

|

|

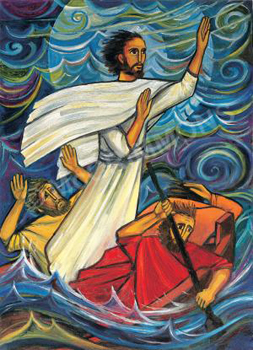

Jesus Calming the Storm — Irish Illuminated Manuscript, 11th Century.

|

I tell this story only to illustrate how completely I sympathize with the disciples' fear. And that's just my personal reaction, borne of nothing more than the memory of some pre-teen recklessness. At the time of this writing, several hundred African migrants, many of them fleeing violence, persecution, and poverty, have drowned in the Mediterranean Sea. Several people have lost their lives in the floods that are ravaging parts of Texas and Oklahoma.

If we extend the meaning of "drowning" to include all the ways in which we human beings find ourselves in over our heads — overwhelmed, overpowered, and terrified — then Jesus' question sounds ludicrous. Why are we afraid in the midst of earthquakes, tsunamis, wars, droughts, terrorist attacks, mass shootings, mass graves, large-scale starvation and catastrophic disease? Why are we afraid when we face broken marriages, depressed children, unfriendly neighbors, grinding jobs, and financial uncertainty?

Um, because we're human? Because fear is a reasonable response to a frightening world? Because God created us with the capacity to feel fear, so that we'll know to pay attention and take reasonable measures to protect ourselves?

I wish I had a neat, uplifting bow to wrap around this question, but I don't. It baffles me. All I can do right now is hope that Jesus asks it of me in love, not irritation. All I can do is trust that the question is an invitation to be honest with God and with myself.

Why am I afraid? I'm afraid because I haven't made my peace with death — mine or anyone's. I'm afraid because I want God to be my life preserver, and it offends me to know that my physical well-being — and the well-being of my loved ones — is not his top priority. I'm afraid because Jesus apparently meant it when he said, "Take up your cross and follow me," and I'm not sure I'm ready.

The next question is a little easier. "Do you still have no faith?" Well, sometimes I do and sometimes I don't. One of the odd things about this story is that Mark surrounds it with a perplexing set of contrasts. In the chapters preceding the calming of the sea, Jesus describes the kingdom of God as small, secretive, and quiet. The kingdom is like a mustard seed, so tiny it's almost invisible. The kingdom of God is like a sower scattering seeds — seeds so vulnerable, they're often snatched by birds or choked by weeds. The kingdom of God is like a farmer whose seeds defy manipulation — they grow when they please.

|

In the chapters which follow, however, Jesus manifests a kingdom of dramatic, supernatural power. He casts out demons, raises a little girl from the dead, heals a hemorrhaging woman, feeds five thousand people with a few handfuls of bread and fish, and walks on water.

To have faith is to hold these two pictures of the kingdom in tension. To allow God to reveal himself in both. Yes, sometimes Jesus demonstrates his power in miraculous, Technicolor ways; we're not wrong to hope for such demonstrations. At other times, though, he wants us to trust that his Incarnation — his quiet, abiding presence in our lives — is enough. Sometimes, Jesus' power is paradoxical; it comes to us in seeming weakness, in quiet whispers and tiny gestures. The hiddenness of God, in other words, is simply that. Hiddenness, not absence.

The last question in the story returns us to the disciples. After Jesus calms the storm, Mark writes, the disciples "fear a great fear." It's no longer the elements that terrify them; it's Jesus. "Who is this man?" they ask each other in awe. "Even the wind and waves obey him!"

I hope I'll always find the courage to ask this question. That is, to allow Jesus to make himself strange to me. Strange, new, unnerving, Other. The disciples thought they had him pegged, but they didn't. He was wilder, more powerful, less predictable, and more mysterious than they had yet imagined.

If we have Jesus pegged, then we're in serious trouble. If he's familiar enough to make us either complacent or contemptuous, then it's time to defamiliarize him one more time. It's time to ask the question again.

"Teacher, don't you care that we are drowning?"

"Why are you afraid?"

"Do you still have no faith?"

"Who is this man?"

When you hear the question that is your question, you have begun to hear much. When you hear the question that is your question, press in close and listen: God is near.

Image credits: (1) Wikipedia.org; (2) Pinterest.com; and (3) ArtsyWanderer.WordPress.com.