For Sunday June 28, 2015

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year B)

2 Samuel 1:1, 17–27 or Wisdom of Solomon 1:13–15; 2:23–24

Psalm 130 or Psalm 30 or Lamentations 3:23–33

2 Corinthians 8:7–15

Mark 5:21–43

In his book Through the Eye of a Needle (2012), the historian Peter Brown of Princeton debunks two myths about faith and wealth in the early church — that of "the primal poverty of the early Christians," and second, that the conversion of Constantine unleashed massive contributions by the mega-rich.

Enormous wealth eventually poured into the church, but not until the late fourth century. Until then, Brown credits the down-market "mediocres" or "in-betweeners" with being the church's biggest supporters. He calls them the "middling people" who were neither rich nor poor — artisans, small farmers, town clerics, tradesmen, and minor officials. These people were "the solid keel of the Christian congregations through the fifth century."

Brown's socio-economic scenario rings true in this week's epistle. Recall how Paul described the Corinthians: "Not many of you were wise by human standards; not many were influential; not many were of noble birth."

In 2 Corinthians 8-9 Paul encourages these "middling" Corinthians in "the grace of giving" to a famine relief effort to feed people in Jerusalem. Paul was repeating himself here. He had already addressed this matter in 1 Corinthians 16, instructing them to set aside money each week for "your gift to Jerusalem."

There's a bitter irony here. It was the original Jewish disciples in Jerusalem who sold their possessions, shared equally with all who were in need, and organized a "daily distribution of food" to their widows. Now, they were the needy, and it was the Gentiles who supported them.

Famine relief flowed to Jerusalem from several far flung churches. In Acts 11, the believers in Antioch sent money to Jerusalem during the reign of the Roman emperor Claudius, who ruled from 41-54 AD. Ancient historians like Tacitus, Seutonius and Josephus describe the food shortages, crop failures, droughts, and bad harvests during his reign.

Paul also describes this "contribution for the poor among the saints in Jerusalem" in Romans 15:26. And just like he does in writing to the Corinthians, he mentions the generosity of the churches in Macedonia — Philippi, Thessalonica, and Berea. Despite their "severe trials" and "extreme poverty," the Macedonians distinguished themselves with their "rich generosity" that was "even beyond their ability."

|

|

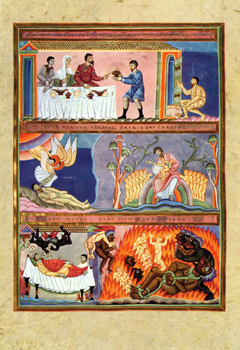

Lazarus and the Rich Man, illuminated mss., 11th-century Codex Aureus Echtermach.

|

Three centuries later the pagan emperor Julian the Apostate (361–363), who vehemently opposed Christians and stripped them of their rights and privileges, acknowledged the generosity of Christians: "The godless Galileans feed not only their poor but ours."

It's remarkable to see how early formal relief efforts were organized, how sophisticated they were, and how they came to characterize Christians. In Brown's telling, this was due to the extraordinary generosity of the ordinary faithful — the people of Main Street, not Wall Street, the neither rich nor poor, every day believers who helped others a thousand miles away in Jerusalem.

But times changed, and so did the relationship between faith and wealth. In Brown's newest book, The Ransom of the Soul (2015), he turns from the role of wealth in this life to its connection with the soul in the afterlife.

He takes his title from Proverbs 13:8, "The ransom of the soul of a man is his wealth;" and the words of Jesus in Matthew 19:21 and Luke 12:33 about storing up treasure in heaven. Jesus seems to say that there's a transfer of earthly treasure to heaven through alms giving, a spiritual reward for financial generosity.

Christians helped the poor for many reasons. There's no timeless "master narrative," says Brown. He documents the different ways that the social imaginations of early believers grappled with wealth — radical renunciation by the super rich, the "anti-wealth" of the ascetics, care of the poor, the generosity of ordinary believers, and, finally, the clerical stewardship of massive wealth that was accepted as God's providential gift.

Brown's second book, though, focuses on one particular motive for giving to the poor. Eventually, and for many, giving alms became a "purely expiatory action" for the forgiveness of sin. It was a way "to heal and protect one's soul."

Brown admits that this quid pro quo of giving in order to get is an "acute embarrassment" to moderns in general, and "abhorrent" to Protestants in particular. But that's our historical record.

Gary Anderson explores this same theme in Charity: The Place of the Poor in the Biblical Tradition (Yale, 2013). He argues that alms giving is not just a utilitarian act of social justice to help the poor (Bill Gates does that), an ethical act done purely out of principled altruism with no element of self-interest or expectation of reward (Kant), or even merely a sign of a believer's personal faith (the Protestant Reformers).

Rather, for Anderson, a Catholic professor of Old Testament at Notre Dame, alms giving is a "merit-worthy" deed and "the privileged way to serve God." There's a spiritual reward for financial generosity. God will repay the loans we've made to him.

The logic of such thinking led to horrible abuses. By the sixteenth century, Johann Tetzel, Grand Commissioner for indulgences in Germany, was credited with the rhyme, "As soon as the coin in the coffer rings, the soul out of purgatory springs." The original German is just as pithy: "Sobald der Pfennig im Kasten klingt, die Selle aus dem Fegfeuer springt."

|

|

Fresco of Lazarus and the Rich Man at the Rila Monastery in Bulgaria.

|

The selling of indulgences — that is, purchasing the remission of your punishment in purgatory, made Luther's blood boil. Tetzel's ditty even made it into his Ninety-Five Theses (#27): "They preach only human doctrines who say that as soon as the money clinks into the money chest, the soul flies out of purgatory."

On this point, I'm a good Lutheran. I'm opposed to Tetzel and his tribe. You can't pay your way into paradise. Forgiveness is free.

But we shouldn't throw out the baby with the bath water. We shouldn't separate alms and the afterlife too quickly or completely. To borrow from Brown, there must be some way in which heaven and earth are "joined by human agency."

Jesus connected alms in this life with the soul in the afterlife in his Matthew 25 parable about separating the sheep and the goats based upon our care for the hungry, the thirsty, the naked, and the prisoner. And there's his parable about the rich man and Lazarus in Luke 16.

Mother Teresa joined faith and wealth in a counter intuitive way. In her heavenly scenario, there's a grand role reversal — the poor are the benefactors and creditors, while the rich are the beneficiaries and debtors: "Only in heaven," she said, "will we learn how much we owe the poor for helping us to love God as we should."

For my money, that sounds about right.

Image credits: (1, 2) Wikipedia.org.