For Sunday February 7, 2021

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year B)

Isaiah 40:21-31

Psalm 147:1-11, 20c

1 Corinthians 9:16-23

Mark 1:29-39

In her 1989 book, The Writing Life, Annie Dillard reminds us of something that is at once obvious and shocking: “How we spend our days is, of course, how we spend our lives. What we do with this hour, and that one, is what we are doing.”

I can’t speak for you, but I find this straightforward truth disconcerting. Why? Because much of the time, I’m not impressed by how I spend my days, and I don’t want them to “count” as my life. So I tell myself that this day, or that shapeless string of days last week, or that dull six-month stretch two years ago, don’t count. I erase them. What will count (I promise myself), are the days I plan to live in the future. Days filled with intention, purpose, and meaning. Days meticulously scheduled and faithfully executed. Days marked by attentiveness, order, devotion, and beauty. When I get around to living those days — maybe tomorrow? Maybe next month? — then I will begin to sculpt my life.

It’s a fantasy, of course, because Dillard is right. How we shape the quotidian is how we shape our existence. Our mundane hours are just as illustrative — more so, really — than our occasional mountain top moments. How we spend our days is how we spend our lives.

In our Gospel reading this week, St. Marks shows us a day in the life of Jesus. As the Messiah begins his public ministry, we have an opportunity to follow him around for twenty-four hours, observing what he does, what he says, and what he prioritizes.

In typical Markan fashion, this section of the Gospel races from one event to the next, favoring speed over depth. Still, if we look carefully, we can find moments to linger over, and lessons to savor. What might we learn if we journey with Jesus through a day of his life?

|

Before we delve in, though, a reminder of grace: my intention is not to hold up Jesus’s daily schedule as a formula or measuring stick for our own. The point isn’t to compare our days to his, and despair at our inadequacy. The point is to trust that we are saved not only by Jesus’s death and resurrection, but also by his life. Reflecting on that life is nourishing and salvific; it moves us closer to Christlikeness, and closer to the compassionate heart of God.

So, a day in the life. Here’s how Jesus spends it:

He makes the home sacred: Our lectionary begins with Jesus leaving the synagogue after Sabbath worship, entering the home of Simon and Andrew, and spending the rest of the day in that domestic space. This might sound like a trivial detail, but I love the fact that Jesus lingers at home, blessing a humdrum, everyday location with his presence, and honoring it as a sacred site where the work of God’s kingdom goes forward.

We know from the rest of the gospels that some of Jesus’s most significant encounters happen in homes. He performs his first public miracle at a home in Cana. He raises Jairus’s daughter in the synagogue leader’s house. His friend, Mary anoints him with oil at her home in Bethany. Salvation comes to Zacchaeus when the despised tax collector welcomes Jesus as a houseguest. And the disciples on the road to Emmaus recognize Jesus when he breaks bread at their dinner table.

Holy things happen in the places we call home. God’s power and presence are not limited to “official” sacred spaces. Our living quarters are not “second best” when it comes to seeking and finding Jesus. If anything, Jesus delights in the domestic.

For me, this delight is a particular comfort during these days of Covid, when I am largely confined to my home. There have been so many days in the past year when I’ve felt restless, trapped, and in limbo, as if “real life” has been suspended, and nothing spiritually significant will happen until the world’s lockdowns and quarantines are over. I’m grateful to know that Jesus isn’t put off by the mundane as I am; he does amazing work in spaces I consider familiar and ordinary. What would it be like for us to honor our homes as Jesus honors Simon’s in our Gospel reading? To elevate our living spaces as sites for the sacred?

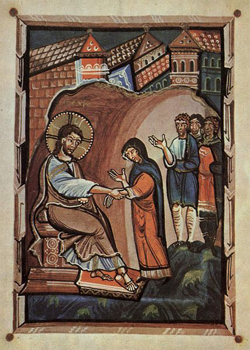

He heals: Jesus’s first act in this week’s reading is to heal Simon’s mother-in-law. Hearing that she’s feverish and bedridden, he goes to her side, takes her by the hand, and lifts her up. Immediately, the fever leaves her body, and is restored to health. Some hours later, the “whole city” gathers around Simon’s door, likewise seeking healing from various diseases and demons. Again Jesus cares for them as a compassionate healer, curing many.

I’ll be the first to admit that I don’t always know what to do with Jesus’s healing stories. Is it just me, or have things changed rather drastically since he walked the earth two thousand years ago, ushering in God’s kingdom with all manner of miraculous signs and wonders?

“The problem with miracles,” Barbara Brown Taylor writes, “is that it is hard to witness them without wanting one of your own. Every one of us knows someone who is suffering. Every one of us knows someone who could use a miracle, but miracles are hard to come by.”

This has always been true, but I find Taylor’s words particularly piercing in the context of the pandemic. Don’t get me wrong — I love the healing stories in the Gospels. I love the power and compassion with which Jesus touches the sick and the suffering. But sometimes I wish that Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John had included a few less dramatic stories in their books, too. Did Jesus ever, for example, visit a feverish woman, take her hand, and offer only the comfort of his presence — without curing her? Did he ever sit in the dark with a profoundly depressed man — just sit? Did he ever keep vigil at a deathbed, and cry with the family as they said goodbye? No resurrection — just tears? Did he ever experience God’s “no,” or God’s “wait,” when he sought to heal someone?

|

Obviously, I don’t know the answer to these questions. But I hang onto them as possibilities. What I know is that Jesus spent many hours of his life offering whatever compassion, healing, and liberation he could. In this week’s story, he heals “many” — not all. He casts out “many demons” — not all. But the “not all” doesn’t stymie him; he still touches everyone who reaches out for help, because touch in and of itself is an instrument of hope and healing. He loves without measure, because love cures many ills. He doesn’t assume that illness and demon possession are punishments from God, because such assumptions are cruel and wounding.

In short, he offers the sick and the broken his steady presence, his warm grip and embrace, and the good news of a kingdom that is coming — a kingdom without sickness, without sorrow, without fear. And his offers are enough.

Maybe our task as healers isn’t to perform magic. Maybe spending our days as Jesus spent his means living graciously and compassionately in this vast and often terrible in-between. To offer the comfort of our steady presence to those who suffer. To encourage those in pain to hang on, because the work of redemption is ongoing. To create and to restore community, family, and dignity to those who have to walk through this life sick, weak, and wounded — without cures. And to make sure that no one who has to die — and that’s all of us, in the end — dies abandoned and unloved if we can help it.

He liberates and commissions: Mark’s Gospel tells us that as soon as Jesus heals Simon’s mother-in-law, she “begins to serve.” I’ll be honest: my initial reaction to this detail was disappointment and frustration. Of course, I thought, the poor woman has to leap out of bed and serve the men in her house the second her fever leaves her. Of course no one allows her to rest and regain her strength for a few hours. Of course the men don't serve her. Isn’t that so typical of this sexist world?

Maybe. Maybe what we’re reading in this story is sexism, pure and simple. But I wonder. The verb St. Mark uses to describe the mother-in-law’s service is the same verb the gospels use to describe the angels who attend Jesus after his forty days in the wilderness. It is the same verb Jesus uses to describe himself when he washes his disciples’ feet: “I am among you as one who serves.” And it is the same verb the early church uses to commission deacons, the “servant” leaders of the church.

What if Simon’s mother-in-law is not an undervalued woman in a patriarchal system, but the church’s first deacon? The first person Jesus liberates and commissions into service for God?

If nothing else, it is interesting to note that this unnamed woman recognizes and pursues her calling long before her son-in-law and his friends do. While Simon and his gang bumble around, getting in Jesus’s way, this woman gets to work without hesitation or self-consciousness, engaging in grateful ministry alongside Jesus. In healing her, Jesus also liberates and commissions her. Though we know little else about the woman’s life, we can safely assume that her ministry is effective. In 1st Corinthians, we read that Simon Peter’s wife accompanies him on his apostolic journeys after Jesus’s resurrection and ascension. Clearly, Simon's mother-in-law has a profound and long term impact on the faith of her daughter and her extended family.

Insofar as we are invited to heal, we are also invited to free others for the service of God. We’re invited to pay attention, to notice, and to bless the gifts and abilities of those around us. Like Jesus, can we spend our days as liberators, commissioning God’s beloved to serve in gratitude and love?

|

He prays. The next morning, St. Marks writes, while it’s still dark, Jesus goes to a deserted place to spend time with God. This is not a one-off; we know from the other gospels that prayer was one of Jesus’s daily practices: "But Jesus often withdrew to lonely places and prayed” (Luke 5:16). “After he had sent the crowds away, he went up on the mountain by himself to pray; and when it was evening, he was there alone" (Matthew 14:23).

In seemingly "minor" verses like these, we see glimpses of Jesus' deeply rooted spiritual life, the source of his strength and vision. We see his need to withdraw, his hunger for solitary prayer, his inclination to rest, recuperate, and reorient his heart. These glimpses take nothing away from Jesus' divinity; they enhance it, making it richer and all the more mysterious. They remind us that the Incarnation truly is Christianity's best gift to the world. The Christ — the Messiah of the whole universe — prays, rests, reflects, and meditates. He needs time alone. He needs time alone with God. He is just like us.

Also like us, Jesus understands the ongoing and necessary tension between compassion and self-protection in a world bursting with desperate need. Jesus lives with this tension every day, and he is unapologetic about his need for rest and solitude. Even as the crowds throng to him, he feels no shame in retreating when he needs a break.

This is an apt lesson for those of us who live in cultures where tireless striving is a virtue, and the need for rest is considered a weakness. It’s also a challenge to those of us who might think about prayer a lot — without actually setting aside time to pray. When our hours and days are measured, how many of them will we have spent alone with God?

He moves on: Our gospel reading ends with Jesus leaving Simon’s house so that he can take the good news of God to other towns, other synagogues, other homes. He makes this decision despite the fact that his disciples interrupt his prayer time to tell him that “everyone” is still searching for him back at Simon’s house. Clearly, there are compelling reasons for Jesus to stay where he is. But his response is to set a boundary. To say no. To move on in keeping with his own sense of mission and timing.

Given Jesus’s compassionate heart, I can’t imagine that he makes this decision lightly. I imagine it costs him something. But after a morning of prayer and reflection, he recognizes and trusts the voice that says, “It’s time to go.”

Can we learn anything from Jesus’s choice? Can we learn to hold calling, timing, and need in productive tension? Can we trust that sowing a seed and walking away is sometimes enough? Can we relinquish fame and power, and choose obscurity instead? Can we risk the new and the unknown? Can we hold firm to our sense of vocation even when our loved ones don’t understand or agree with our choices? Can we establish and honor healthy boundaries? As we sculpt the hours that make up the days that make up our lives, who or what directs our decisions? Are we, like Jesus, able to let go and move on?

How we spend our days is how we spend our lives. May we, like Jesus, spend ours well.

Debie Thomas: debie.thomas1@gmail.com

Image credits: (1) Aleteia.org; (2) BigBible.uk; and (3) Jerusalem Perspective.