For Sunday March 14, 2021

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year B)

Numbers 21:4-9

Psalm 107:1-3, 17-22

Ephesians 2:1-10

John 3:14-21

What happened at the cross? How exactly did Jesus’s crucifixion two thousand years ago secure salvation for humanity? Which “theology of atonement” is the “correct” one?

I spent many years agonizing over these questions. When the version of the atonement I was taught as a child fell apart for me (the version that says Jesus died as my “substitute,” absorbing God’s fury over my wickedness into his own body), I scrambled to enthrone a new one. As if this greatest of mysteries — this deep, holy well of love, grace, mercy, judgment, sinfulness, pain, death, and reconciliation — wouldn’t hold and wouldn’t work, unless I pinned it down and figured it out.

Thankfully, I no longer believe this. I know now that it’s neither lazy nor wishy-washy to approach the cross with awe rather than analytical acumen. Not because my curiosity is wrong, but because all of our explanations of God’s saving work are necessarily partial and incomplete. What the cross offers (if we can bear to receive it) is overabundance — a vast richness of meanings, approaches, angles, and truths. The gift God gives us at Calvary is the gift of contemplation — not the gift of perfect comprehension.

During this fourth week of Lent, our lectionary offers us one approach, one way of asking the question, “What happened at the cross?” Again, it’s not an exclusive or exhaustive way. But it’s a compelling way, as challenging as it is beautiful, and I’m grateful to have it as one option among many.

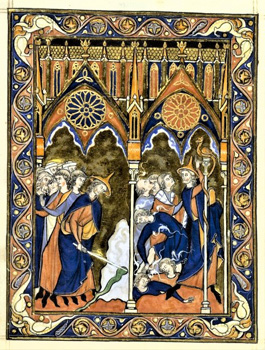

We find it via a pairing of stories — one from the Old Testament Book of Numbers, and one from the Gospel of John. In the Old Testament story, the Israelites, having lost patience yet again with the hardships of life in the desert, speak out against God and Moses. “Why have you brought us up out of Egypt to die in the wilderness?” they ask. “For there is no food and no water, and we detest this miserable food.”

|

Their complaint is the final one in a long line of “murmurs” — murmurs that until this point in the post-Egypt narrative, God answers with compassionate, long-suffering care. When the Israelites complain that their drinking water is bitter, God instructs Moses to sweeten it. When they grumble about their hunger, God provides them with manna. When they cry out in thirst, God instructs Moses to strike a rock and produce abundant water. When they despair for lack of meat, God causes flocks of quail to fly into their camp.

This time, though, God’s response to their complaining is not so benign. According to the text, God answers their “we-want-to-go-back-to-slavery” whine-fest by sending poisonous serpents into their midst. The serpents bite them, and several of them die of the fiery, painful bites.

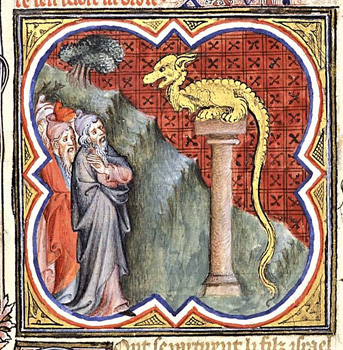

Yes, it’s an inconvenient story that raises thorny questions about sin and judgment, and it’s okay to wrestle with it. But for the purposes of approaching the cross and the atonement, I want to focus on what happens next. The people repent of their sin, and beg Moses to pray on their behalf. When Moses does so, God says, “Make a poisonous serpent, and set it on a pole; and everyone who is bitten shall look at it and live.”

As instructed, Moses makes a serpent of bronze, and sets it high on a pole. When the people who’ve been bitten look up at the serpent, their snakebites are healed, and they live.

Okay. Now fast forward several centuries, to the conversation John’s Gospel records between Jesus and a Pharisee named Nicodemus. When Nicodemus approaches Jesus under cover of night to inquire about God, they enter into a long and bewildering dialogue about birth, light, Spirit, and belief. At one point in the conversation, though, Jesus refers back to the ancient story from Numbers which Nicodemus must know inside out, and says this: “Just as Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, so must the Son of Man be lifted up, that whoever believes in him may have eternal life.”

|

“Just as Moses lifted up the serpent, so must the Son of Man be lifted up.” What an odd comparison, the loving, saving Messiah to the bronze replica of a poisonous snake. What does it mean?

I wonder if it means something about perspective. About seeing. About casting our eyes in a new and less comfortable direction. In the Old Testament story, God requires the Israelites to look up. To gaze without flinching at the monstrous thing their sin has conjured. It’s the thing they have wrought, the thing they fear most, the thing that will surely kill them if God in God’s mercy doesn’t intervene and transform the instrument of pain and death into an instrument of healing and life. In order to be saved, the people have to confront the serpent — they have to look hard at what harms, poisons, breaks, and kills them.

Sometimes, it’s hard to understand that the kind of love that will save us might “wound” us first. In this case, the Israelites have to see in the serpent the outworkings of their own failure to trust God — the God who delivered them from slavery, sustained them in the desert, and promised to guide them into the nourishing sweetness of a new homeland. They have to understand that their ongoing failure to trust in this God has stakes. It matters. What they need is not “belief” in the sense of intellectual assent to a set of abstract propositions about God — what they need is full-bodied, heart-and-soul confidence in God’s goodness, presence, provision, and love.

Hence the bronze snake, which forces them to stare the poison down until they see in it the grief, the anger, the judgment, and the unending mercy of a God whose love is vast but tough, deep but demanding. It’s a love that will heal but also expose truth — truth that hurts. It’s a love that will deliver but at the same time invite a change in perspective, a shift in apprehension, a bitter but ultimately salvific “looking up.”

What might this story of a serpent on a pole illuminate about the cross of Jesus? For those of us who struggle to reconcile the role of God's will in the death of God’s Son, perhaps this story offers a way in. It was the will of God that Jesus declare and embody the coming of God's kingdom. A divine kingdom of peace, of restorative (not retributive) justice, of radical and universal love, grace, freedom, and hope. A kingdom without violence, without oppression, without exploitation, without greed. In short, a kingdom dramatically unlike the all-too-broken, all-too-human one Jesus was born into.

|

So why did Jesus die? He died because he unflinchingly fulfilled the will of God. He died because he exposed the ungracious sham at the heart of all human kingdoms, holding up a mirror that shocked his contemporaries and still shocks us at the deepest levels of our imaginations. In other words, he unveiled the poison, he showed us the snake, he revealed what our human kingdoms, left to themselves, will always become unless God in God’s mercy delivers us. In the cross, we are forced to see what our refusal to love, our indifference to suffering, our craving for violence, our resistance to change, our hatred of difference, our addiction to judgment, and our fear of the Other must wreak. When the Son of Man is lifted up, we see with chilling and desperate clarity our need for a God who will take our most horrific instruments of death, and transform them, at great cost, for the purposes of resurrection.

The bronze snake of Moses’s day was not magical. It was not meant to be idolized. Neither is the cross we contemplate during this Lenten season. But insofar as the cross invites us to look up, to reorient ourselves, and to depend wholly on God to bring life out of death, light out of shadow, and healing out of pain, then the cross functions as a sacrament. A means of grace. A path to the divine. It reminds us that “belief” is far more than a cognitive exercise. To believe in the power of the cross is to rely on Jesus for our very lives. It is to trust that the lifting up of the Son of Man is our only hope, our only "anti-venom," our only means of rescue.

The cross of Christ is a great mystery — and that is as it should be. Among many other things, it is a stunning paradox of sorrow and hope, judgment and mercy, despair and healing, brokenness and hope. It’s okay not to understand — the invitation is to see. So look up. Don’t be afraid. Don’t refuse the pain. Don’t turn away. Look up and be saved.

Debie Thomas: debie.thomas1@gmail.com

Image credits: (1–3) Ad Imaginem Dei.