For Sunday June 20, 2021

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year B)

1 Samuel 17:1a, 4-11, 19-23, 32-49

Psalm 9:9-20

2 Corinthians 6:1-13

Mark 4:35-41

My son is taking a "Philosophy 101" class this semester, one of those broad undergraduate courses that offer students a sweeping overview of a huge academic field. The syllabus includes many of the big questions that have stimulated human thought for millennia: do we have free will? How can we know things? What does it mean to be moral? Is there a God?

For better or for worse, my son’s professor has been honest and vocal about his own atheism, offering his students numerous arguments to support the view that God doesn’t exist. Unsurprisingly, the problem of evil, or (in more theological terms), the question of theodicy, has been central to his claim. In short: an omnipotent, omniscient, benevolent, and loving God would not allow evil, chaos, and suffering to exist within God’s good creation. But of course, evil, chaos, and suffering do exist. So God does not.

It’s an ancient argument, and the aim of this essay is not primarily to refute it. As a Christian who does believe in God, though, I am very interested in the ways we church folk dance around the question. If we begin with the assumption that God exists, then what do we do when chaos engulfs our lives? What mental and spiritual gymnastics do we engage in? How do we bridge the gap between our theism and our suffering?

Some versions of Christianity teach us that suffering is a result of faithlessness. If only we’d believe more, trust more, pray more, worship more, then God would grant us the immunity that is our true Christian birthright. Some churches teach its members that chaos and suffering are direct punishments from God. People who face painful trials in such churches are exhorted to confess their “secret” sins and return to holy living, so that God will relent and forgive them. Other (perhaps more “liberal”) versions of Christianity attempt to get around the problem by positing a God who is more transcendent (above, beyond, and detached) than immanent (personal, affectionate, and directly involved in our everyday lives.)

|

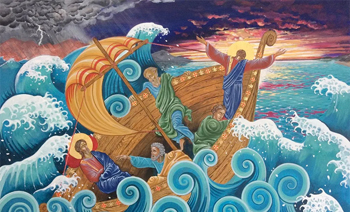

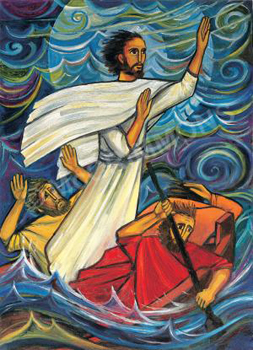

In our Gospel reading from Mark this week, Jesus’s disciples offer us yet another iteration of this all-too-human dance. The setting is late evening on the Sea of Galilee — a body of water 680 feet below sea level, surrounded by hills, and prone to sudden, violent windstorms. After a long day spent preaching, Jesus is curled up at the stern of a boat, sleeping soundly as his disciples steer the vessel. According to Mark, their boat is surrounded by a small fleet of others. All at once, the winds pick up, huge waves lash the boat, and the disciples, seasoned fishermen though they are, fear for their lives.

In desperation, they rouse the still-sleeping Jesus: "Teacher, don't you care that we are drowning?" It’s not a question; it’s an accusation. A ghastly, hidden terror that the disciples’ dire circumstances pull to the surface: “Jesus, this is not the way things were supposed to go! You told us to get into this boat, and now we’re in deathly trouble. We followed you. We trusted you. Aren’t you supposed to do something? Why are you asleep? The only possible explanation is that you don’t care.”

I can’t tell you how many times, in how many subtle and not-so-subtle ways, I have flung this accusation at God. How many times I’ve linked my suffering to God’s (apparent) lack of care. How many times I’ve bruised my faith on the assumption that chaos is always and everywhere an unholy aberration, its very existence in my life a proof of God’s apathy, God’s coldness, God’s indifference — and maybe even God’s non-existence.

|

Never mind that in Genesis, God creates and hovers over chaos (an earth without form, void, watery, and dark) before God creates order. Never mind that in his nighttime conversation with Nicodemus, Jesus describes the Holy Spirit as a wild, free wind that blows where she wills — a wind that will not be traced or controlled. Never mind that Jesus’s entire ministry on earth is steeped in the “chaos” of upended hierarchies and rocked boats.

How quickly all of this nuance disappears when the sky darkens and the waves swell. “Don’t you care that we are drowning?”

To be fair, the disciples’ response to the sleeping Jesus has a rich and storied Biblical history. The Hebrew scriptures are full of such questions and accusations. Where are you? Why won’t you save us? How much longer? Rouse yourself, Lord! Why have you forsaken us?

I take refuge in this history because it means I’m in good company. It’s not a sin to ask God hard questions. It’s not unfaithful to wonder “Why?” or “When?” or “How much longer?” It’s not wrong to be afraid; God has wired us to experience fear when we’re threatened.

The problem isn’t fear; the problem is where fear leads. When I face fearsome circumstances, my go-to position is not trust or even curiosity; it's full-on suspicion. In my fear, I conjure up a God who is stony-faced, implacable, and loveless. A God to whom I am expendable. A God who withdraws. Once I’ve conjured that God, I withdraw, too. I curl up tight and focus on mere survival, convinced that I’m alone. All capacity for reflection disappears.

But consider this: in Mark’s story of the storm, the obvious (but wholly overlooked) fact is that Jesus is just as present in the raging water as he is in the soothing calm that follows. Despite the disciples’ inability to perceive it, there is no point in the night when God is absent or even distant. In that vulnerable boat, surrounded by that swelling, terrifying water, the disciples are in the intimate company of Jesus. He rests in their midst, tossed as they are tossed, soaked as they are soaked.

|

I think I will spend the rest of my life seeking this one grace — the grace to experience God’s presence in the storm. The grace to know that I am accompanied by the divine in the bleakest, most treacherous places. The grace to trust that Jesus cares even when I’m drowning. The grace to believe in both the existence and the power of Love even when Jesus “sleeps.” Even when the miraculous calm doesn’t come.

In his great tenderness, Jesus waits until the nightmare is over before he invites his disciples to take spiritual inventory. “Why are you afraid?” he asks them. I don’t read his question as an accusation. I read it as an invitation to take stock, to reflect, to learn, to grow. Why are we afraid as Christians? What false assumptions do we harbor about the character of God? What damaging lessons have we learned about the relationship between chaos and care that we need to jettison? Are we more interested in God being with us, or doing things for us?

After Jesus calms the storm, the stunned disciples ask the most important question of all: "Who is this man?" Indeed. Who is this man, this Christ, this God, who sleeps through storms, accepts our accusations, and offers us his quiet, mysterious presence in wild and wind-swept places? Who is this God who loves us in the chaos?

In one of our conversations about his philosophy class, my son noted that suffering and evil don't always lead to a loss of faith. Often, the harsh realities of this broken, disordered world are what draw people to faith. We seek the good because we experience the bad. We yearn for justice because injustice surrounds us. We pray for calm because chaos brings us to our knees.

It’s after the vicious storm that the disciples recognize the holy in their midst. It’s after the boat fills with water that they are “filled with a great awe.” It’s after Jesus accompanies them in the chaos that they realize who he is. May the same be true of us.

Debie Thomas: debie.thomas1@gmail.com

Image credits: (1) Bible Matrix; (2) Icons and Their Interpretation; and (3) Artsy Wanderer.