For Sunday October 17, 2021

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year B)

Job 38:1-7, 34-41

Psalm 104:1-9, 24, 35c

Hebrews 5:1-10

Mark 10:35-45

NOTE: This essay looks at the Old Testament reading. For a reflection on this week’s Gospel, see “What Glory Looks Like,” from the JwJ archives.

Perhaps the first thing to say about this week’s reading from the book of Job is that we’re not meant to find it pleasing. Humbling? Yes. Baffling? Most likely. Infuriating? Perhaps. But not pleasing. Like the rest of this ancient and complicated text, the closing chapters of Job invite us to wrestle. To push our boundaries. To contend with the frustrating limits of our comprehension and knowledge. In many ways, God’s thundering response to Job’s anguished questions about human suffering is an invitation for us to accept what we’d much rather not accept: the unknowable.

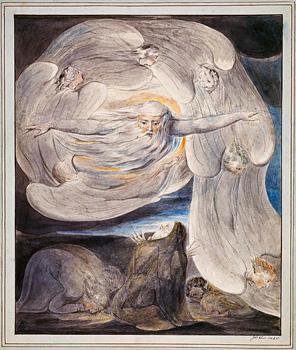

The reading opens just as God appears in a whirlwind and confronts his “faithful and upright” servant, Job. For thirty-seven chapters, we have waited for this climactic moment. In rapid, horrible succession, we’ve watched Job lose nearly everything he cherishes in this world. We’ve witnessed his sorrow, his bewilderment, his anger, his despair. We’ve sat with him in the ashes and contemplated the injustices that scar our own lives. We’ve listened to the unhelpful blather of Job’s friends, and recognized in their pious speeches some of the harmful things we ourselves believe about suffering. We’ve longed, like Job, for clarity. For answers. For vindication. For far too long, we’ve pleaded with God just as Job has, daring God to break God’s silence, and show up.

So what should we do now? How should we respond to the God who does, in fact, show up in our lectionary? Not to answer even one of Job’s searing questions, but to flatten the poor man with another set of questions that leave him speechless?

|

“Where were you when I laid the foundation of the earth? Who has the wisdom to number the clouds? Can you send forth lightning? Who can tilt the waterskins of the heavens? Who provides for the raven its prey? Have you entered into the springs of the sea, or walked in the recesses of the deep? Have the gates of death been revealed to you? From whose womb did the ice come forth, and who has given birth to the hoarfrost of heaven? Can you bind the chains of the Pleiades, or loose the cords of Orion?”

On and on and on God goes in this gorgeously poetic text, describing a cosmos so vast, so complex, and so intricate in its workings that even our modern, scientifically-oriented minds buckle. But why? Why is this barrage of impossible questions, this dazzling, dizzying tour of the natural world, God’s response to Job?

I wonder if the divine intention is two-fold. On the one hand, God honors and elevates Job by showing up and engaging him in dialogue. After all, what else has Job asked for since his good life shattered? He has asked for God’s presence, God’s voice, God’s nearness. In respecting this desire, God extends a “high” anthropology to Job -- a high view of humankind and its relationship with the divine. According to the author of Job, human beings are creatures with whom God interacts and argues. Human beings are free to question God, challenge God, doubt God. Human beings matter enough in the cosmic scheme of things to be confronted with hard truths by their creator. If anything, Job’s honest and impassioned response to his very human suffering -- a response wholly devoid of his friends’ smug pieties -- earns him the divine audience he craves.

|

At the same time, though, God’s cosmic nature lesson reorients Job, handing him a “lower” anthropology, a more modest position in God’s economy. Like most of us, Job organizes his theology around his own experience. He uses his own story, his own pain, as the foundation for his beliefs about God. Suffering does this to us; it narrows and clouds our vision, making a “big picture” perspective difficult.

Another way of saying this is that Job thinks he lives in an “if-then” universe that centers around his own tragedy. “If I do A, then B will happen. If I live righteously, then God will reward me.” God’s response to Job challenges this spiritual myopia. Humanity’s place in creation is honorable but not exclusive, significant but not central. God’s perspective on justice for humanity is not bound by Job’s retributive calculus. Of course God cares for Job. But God also cares for the creatures of the forest, the movements of the planets, the patterns of the weather, the currents of the sea. God’s concerns are much wider, broader, deeper, and higher than Job’s puny mind can fathom, and the way that causality might or might not work in God’s universe has nothing to do with Job’s wholly human-centered “if-then.”

I started this essay with the claim that God’s response to Job is not a pleasing one. It’s not a pleasing one if we come to the book of Job seeking a straightforward answer to the question of human suffering. To put it bluntly, God doesn’t answer the question. Instead God asks us questions, questions intended to show us how little we’re capable of knowing about God, the universe, and ourselves. Whatever the answer to Job’s question might be, this ancient text insists that we can’t approach, grasp, or comprehend it. It is as beyond us as the foundations of the earth, the wisdom of the clouds, the chains of Orion. In this sense, God’s response to Job is a tender one. A loving one. A parental one. It is the answer of a wise and careful parent who reminds her child that there are limits he must respect, whether he likes them or not.

|

Are we meant to feel a tad dissatisfied? I think so. It’s painful, after all, to be told, “No.” It’s frustrating to be confronted with the unknowable. Interestingly, Job doesn’t respond to God’s barrage of questions with displeasure. He responds with wonder, humility, and repentance: “I have uttered what I did not understand, things too wonderful for me, which I did not know…. Therefore I despise myself, and repent in dust and ashes.”

Perhaps this is the point. Not to be pleased or satisfied, but to be baffled into wonder. Startled into humility. Disoriented into praise. To ponder the unknowable is to be silenced into a newer, wider kind of attentiveness to God and all that God has made. Yes, suffering remains, and so do the questions that must arise from it. But the story of Job reminds us that we ask these questions in the context of a universe securely held, ordered, protected, and cherished by God. In knowing this much, we might find rest.

Debie Thomas: debie.thomas1@gmail.com

Image credits: (1) Sermon From the Fast Lane; (2) Wikipedia.org; and (3) Wikimedia.org.