For Sunday October 24, 2021

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year B)

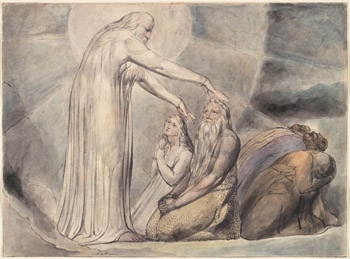

Job 42:1-6, 10-17

Psalm 34:1-8, (19-22)

Hebrews 7:23-28

Mark 10:46-52

NOTE: This essay looks at the Old Testament reading. For a reflection on this week’s Gospel, see “Let Me See Again,” from the JwJ archives.

What are we supposed to do with the ending of the book of Job? God speaks, the long-suffering Job repents, God doubles Job’s wealth and prosperity, and Job lives happily ever after. Are we meant to look up from this fairy tale ending and applaud? Give thanks? Flinch?

Scholars have long questioned the “restoration” that concludes Job’s story, and they’ve done so for good reasons. Why write a lengthy narrative challenging the notion of retributive justice (justice that punishes the wicked and rewards the righteous), only to validate it at the end? Why compose such profound and heart-wrenching poetry about human suffering, and then flatten that suffering with a facile ending?

At a more visceral level, what does it mean to suggest that God “restores” Job’s catastrophic losses by giving him new children? The very thought that a child we lose to death can be replaced by another is cruel and obscene. So again: what are we supposed to do with this story?

I think we’re meant to engage it, talk back to it, question it, lament it. As with the rest of the Bible, we’re invited to approach Job’s story honestly, trusting that God’s Word doesn’t need our pious shielding. Scripture can handle our questions. Our bewilderment. Our resistance. Our fears. The Bible can bear what Lutheran pastor Emmy Kegler calls, “a hermeneutic of the hip,” an interpretative wrestling akin to Jacob’s in the book of Genesis. Sometimes, we have to fight with the scriptures, and walk away limping. Sometimes, the Spirit bruises and blesses us at the same time.

Wrestling with God’s Word looks different for each one of us, and yields results specific to our circumstances. As I’ve reflected on Job’s “happily ever after” this week, here is some of what has bruised and blessed me:

|

There’s beauty in the cacophony. I was raised to read the Bible as an unambiguous text, a text that offers us one single, internally coherent picture of who God is and how God works in the world. But in fact, the Bible is not univocal in its descriptions of the divine; it is a polyvocal, multigenerational library of conversations with God and about God. What we hear in scripture is a rich, meaning-laden cacophony of voices testifying to an ever-shifting, ever-evolving comprehension of faith. Is God immutable, or does God change God’s mind? Does God intervene directly and intimately in human history, or is the divine presence more subtle and stealthy? Are human beings free to make their own life choices, or does everything happen according to God’s master plan? The stories of scripture invite us to engage all of these questions, all of these possibilities.

For me, the book of Job illustrates this plurality perfectly. Consider how many distinct voices “do theology” in this Old Testament story, each offering a particular take on questions of human suffering, divine justice, and the natural order. The satan or “adversary” of the narrative holds one view. Job’s friends hold another. Job holds still another, and so does his wife. The God-of-the-whirlwind, meanwhile, has a different perspective entirely. And the unknown author of the book itself — the one who can’t resist writing Job’s “happily ever after?” Perhaps he holds a point of view unlike that of any of his characters.

I wonder if our task is not so much to choose one definitive voice and disregard the others, but to see ourselves mirrored in each of them. When are we like the adversary, goading God with our dares? When are we like Job’s friends, full of well-intentioned but harmful platitudes? When do we — like Job — catch a glimpse of Creation's glory and respond with awe? When do we — like the writer of Job’s story — wrap pretty bows around pain and suffering, instead of sitting with tragedy honestly?

|

Some losses are for keeps. This is why the ending of Job’s story grates on me. It’s simply not true that nothing is ever lost. It’s just plain not the case that everything happens for an ultimately good reason, or that tragedy always makes us better people, or that God owes us shiny, happy endings. When our lectionary tells us that “the Lord restored the fortunes of Job,” giving him twice what he had before calamity ruined his life, I see the writer of this ancient text making a move that’s painfully familiar. It’s a meaning-making move, a parrying move, a survival move. It’s a move to make the reality of suffering okay by somehow canceling it out with blessing. But it’s not, in my opinion, a truthful move.

A truthful move requires us to sit with catastrophe and chaos, and find new life in their wake. It requires us to admit that sometimes we lose things and don’t get them back. It requires us to divorce our trust in God from the fairy tale expectation of “happily ever afters.”

This month is the four-year-anniversary of a biking accident that left my now nineteen-year-old son bedridden with chronic and debilitating headaches. He has not had a single pain-free day since the accident. He hasn’t been well enough to finish high school, apply to college, spend time with his peers, or plan his future. It’s not clear if or when any of these things will happen.

I know that God might heal my son someday. I pray for his healing daily. But even if he wakes up pain-free tomorrow morning, I know that he will not get the last four years of his life back. That loss — the loss of his adolescence with all of its wonderful milestones; the loss of friendship, recreation, adventure, and memory-making; the loss of carefree innocence — is gone for keeps.

What helps me here is the scarred body of the resurrected Jesus. Even in the most triumphant story ever told in scripture or history, scars remain. The embodied memory of pain, loss, trauma, and suffering remain. Yes, God works life out of death. Yes, God redeems and restores. But resurrection is not an erasure of the past. Restoration is not a “making okay” via the promise of new prosperity. Resurrection is a way forward from the grave that honors the scars we carry, helping us to bear them with resilience and hope.

This is not to say that I disbelieve the ending of the book of Job. Job’s story is, among other things, a story about God’s radical and complete freedom. The creator of all things — the maker of the terrifying leviathan and behemoth, the designer of turbulent oceans and destructive thunderstorms — is free to give and free to take away. For me, the ending of Job is one more illustration of this wild and complicated freedom. God is certainly at liberty to restore Job’s wealth and his family. But God is by no means required to do so. The story is not a formula.

|

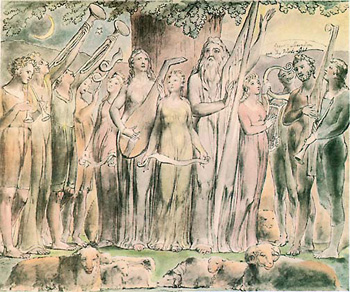

We’re invited to live again. What if we turn Job’s happy ending around, and consider it from his point of view? In her thought-provoking book, Getting Involved with God: Rediscovering the Old Testament, theologian Ellen F. Davis does exactly this. She reads the ending of Job as an affirmative answer to one of the central questions of the book: "Can you love what you do not control?"

When we first meet Job, he is a careful and perhaps even fearful father, a man who covers all bases and secures God’s protection for his family by even praying for his children’s possible sins. What would it take, Davis asks in her book, for a man as cautious and guarded as Job to rise up from the ashes and truly live again after losing his precious sons and daughters? She writes: “This book is not about justifying God’s actions; it is about Job’s transformation. It is useless to ask how much (or how little) it costs God to give more children. The real question is how much it costs Job to become a father again. How can he open himself again to the terrible vulnerability of loving those whom he cannot protect against suffering and untimely death?”

When we last see Job, he is lavishly loving his new children, breaking social custom to give his daughters as well as his sons inheritances, and naming his three beautiful girls with almost mischievous delight: Dove, Cinnamon, and Horn of Eye-Shadow. In other words, when we last see Job, he is choosing life. Choosing courage. Choosing to open his heart to love what he cannot control.

This is the choice that lies before us, too. When suffering comes, when loss shatters our belief in a predictable world and a “safe” God, what will we do? Will we opt out? Will we close our hearts around our wounds and never risk life again? Or will we participate in the lavish, unbounded love of God, who adores a created cosmos that includes contingency, chaos, destruction, and disorder? We are free to choose — just as God is. We are free to risk our hearts or not — just as God is. Can we love what we do not control?

Job is a remarkable book. A difficult book. A book to struggle with. What I’ve found in these last few weeks of wrestling with this timeless story is that God meets me in my resistance and doubt, just as much as God meets me in my trust and surrender. The Spirit is more than equal to everything I bring to the pages of scripture, because my wrestling is always in the arms of God — and so is yours.

Debie Thomas: debie.thomas1@gmail.com

Image credits: (1) My Jewish Learning; (2) Wikimedia.org; and (3) Artwork by Gail Gastfield.