For Sunday December 19, 2021

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

Micah 4:2-5a

Luke 1:46b-55

Hebrews 10:5-10

Luke 1:39-45

It’s almost time. On this fourth Sunday of Advent, as the hectic month of December pulls us ever closer to the sacred story we know and cherish – the story of a census, an inn, a manger, an infant – it’s tempting to leap ahead, I know. But don’t. Please don’t.

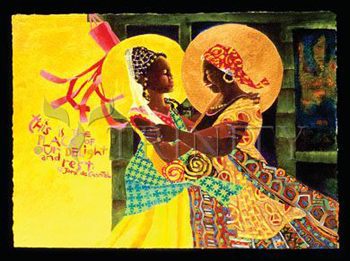

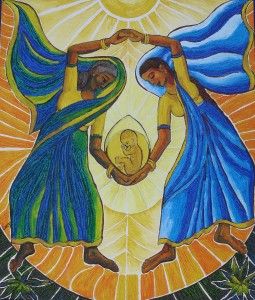

Linger here a little while longer. Linger here on this threshold, in this liminal space, at this ancient doorway where two pregnant women caress each other’s bellies and laugh, marvel, dance, and sing. Linger here as swollen breasts, aching backs, waves of nausea, and wild fetal gymnastics reveal a Savior who enters the world, womb-sized. Linger here with Elizabeth, Mary, the messenger, and the Message, and celebrate the fleshy presence of our God.

|

The story of the Visitation, which the lectionary offers us once every three years, is nothing less than the story of the first Christian worship service in history. The call-and-response of Mary’s greeting and Elizabeth’s leaping uterus, Elizabeth’s prophetic blessing and Mary’s glorious Magnificat, is the first liturgy enacted in a gathered celebration of Jesus the Christ. When Mary, the first evangelist, and Elizabeth the first convert stand at this Advent threshold, what happens between them is Good News. It is the Good News proclaimed, honored, savored, and adored, nine months before the Son of God makes his way through a birth canal. As such, this gathering has much to teach us about authentic and holistic worship.

I, for one, am grateful that the setting of this momentous event is domestic and earthy. I’m grateful that it’s female-centered – a rarity in Scripture. And I’m grateful for the testimony it bears to God’s passionate commitment to holy reversal. The barren conceives. The peasant girl becomes the God-bearer. The mundane, the intimate, and the too-often-discounted (morning sickness, fatigue, varicose veins, and Braxton-Hicks) become the locus of the divine.

|

I know that our more abstracted theologies around the Incarnation have their place. It is right and good to contemplate God’s gift of salvation, the rich resonances of the Logos through whom all things are made and sustained, the radical nature of the kingdom Jesus ushers into the world at his birth. But we make a costly mistake if we separate our worship of God from the vivid details in which God dwells, because those details are alarming and instructive in the best ways. The story of the Visitation reminds us to return again and again to the center of the scandal, the center of the mystery. The center is not abstraction; it is blood, stem cell, placenta, cervix. It is God’s alignment with the material, the embodied, the raw, the messy. It is God looking with favor on what religion so often fears and ignores: real bodies, real lives, the real flesh-and-blood experiences of simple and singular human beings. The story of Mary and Elizabeth’s worship teaches us that God’s preferred realm is the nitty-gritty realm of the forgotten, the fragile, and the unformed.

Luke’s Gospel tells us that when the angel Gabriel leaves Mary, she runs. "With haste," he writes, the newly pregnant teenager makes for the hills which lie eighty miles away, not slowing down until she reaches the home of her also-pregnant cousin. Luke doesn't elaborate on Mary's reasons for leaving Nazareth, but we can easily imagine why a girl in her circumstances would make such an urgent journey.

|

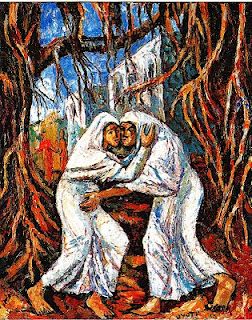

Tradition tells us that Mary is only thirteen or fourteen years old when the angel appears to her. In her cultural and religious context, her pregnancy – unlike Elizabeth’s – is not a gift; it’s a disaster. At best, it renders her the object of gossip, scorn, and ostracism in her village. At worst, it places her at risk of death by stoning. I imagine that Mary runs to put both geographic and psychological distance between her vulnerable body and those stones.

It’s worth noting then, that the worship we see on Elizabeth’s doorstep doesn’t take place at some sanitized remove from fear, pain, and loss. This is worship in the crucible of uncertainty and hardship. This is worship as haven, worship as healing, worship as real-time formation in the spiritual disciplines of trust, hope, and surrender. As Mary falls into Elizabeth’s arms, as the two women exchange stories, as they confirm each other’s testimonies with loving acceptance – genuine praise and wonder erupt between them. They don’t have to scrub their worship clean of all “real life” traces in order to make it faithful. Their worship emerges on a doorstep. Neither-here-nor-there, in-betwixt-and-between, in the tender spaces between yearning and fulfillment. As Mary and Elizabeth mirror for each other the tangible, physical evidence of God’s presence in their lives, their worship emerges in shared communion, shared fear, shared consolation, and shared hope.

Moreover, their worship sits right alongside their hardest questions. Will Joseph stick around? Will Zechariah speak again? Will Mary’s parents disown her? Will the elderly Elizabeth live long enough to see her son reach adulthood? Will both women survive the dangers of childbirth? Will these mysterious babies, these babies of such odd and unfathomable promise, really and truly change the world? Or will they die trying – and shatter their mothers’ hearts with their deaths?

|

Standing together on the precarious threshold of their own unknowing, Mary and Elizabeth find a way to sing God’s praises right from the heart of their burning questions. Elizabeth worships by pronouncing a blessing on Mary’s fierce faith, a blessing that bridges the gap between the tenuous present, and God’s promised future: "Blessed is she who believed that there would be a fulfillment of what was spoken to her by the Lord.” She astutely connects the dots in Mary's story, making explicit the connection between trust and blessing. In Elizabeth's mind, Mary's "favored" status has nothing to do with wealth, health, comfort, or ease. Her blessing lies solely in her willingness to trust God. To lean hard into the angel’s promise, and believe that it will sustain her, no matter what lies ahead.

In turn, Mary finds her own prophetic voice and bursts into a hope-drenched song that soars with promise not only for the child she carries, but also for Elizabeth’s, and indeed for all the world's poor, brokenhearted, forgotten, and oppressed. "My soul magnifies the Lord," Mary sings, and then her song goes on to do just that. To make more visible and clear — to magnify for the world — a God invested in revolutionary and lasting change for Creation. Mary describes a reality in which humanity’s sinful and unjust status quo is gorgeously reversed: the proud are scattered and the humble honored. The hungry are fed and the rich sent away. The powerful are brought down, and the lowly are lifted up. Mary describes a world reordered and renewed — a world so beautifully characterized by love and justice, only the Christ she carries in her womb can birth it into being.

|

As Episcopal priest Barbara Brown Taylor notes so beautifully, Mary describes these divine reversals as if they have already happened: “He has brought down.” “He has filled.” "He has sent." “Prophets,” Taylor writes, “almost never get their verb tenses straight, because part of their gift is being able to see the world as God sees it — not divided into things that are already over and things that have not happened yet, but as an eternally unfolding mystery that surprises everyone, maybe even God.”

What these two women on the cusp of new life celebrate is not the easy answer, the carefree life, the guarantee of prosperity. What they celebrate is a God who sees. A God whose loving gaze is ever on the tiniest and most intimate particulars of their circumstances, their bodies, their desires, their lives. “He has looked with favor,” Mary says. Let’s honor the God who looks, watches, sees, and knows, because we are held fast and forever in that knowing.

Something powerful and transformative happens when we share the fullness of our embodied selves with God and with each other in worship. We see the image of God in each other’s faces, hands, feet – and wombs. In our fear, in our hope, in our uncertainty, and in our surrender, blessing happens. The spaces we create together shimmer with the mysterious presence of God. Laughter becomes holy – and so do tears. Time bends, allowing us, even for a few trembling moments, to perceive the world as God perceives it, bruised and beautiful, raw and redeemed.

It’s almost time. It’s almost time to encounter the divine in a laboring woman’s gasps and cries. In the tremendous power of a contracting uterus. In a rush of blood, sweat, milk, and tears that portend new life. In the arms that hold, the infant who latches, the breast that feeds. Get ready. Linger here on this sacred threshold, and lean in so you won’t miss the details. It’s almost time to worship. It’s almost time for the fulfillment, the glory, the Word made flesh. As the Scriptures have promised us, may all flesh see it together.

Debie Thomas: debie.thomas1@gmail.com

Image credits: (1) TrinityStores.com; (2) Silvepura.blogspot.com; (3) St. Gertrude Monastery; (4) Hanna Strack; and (5) FineArtAmerica.com.