For Sunday August 23, 2015

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year B)

1 Kings 8:1, 6, 10–11, 22–30, 41–43 or Joshua 24:1–2a, 14–18

Psalm 84 or Psalm 34:15–22

Ephesians 6:10–20

John 6:56–69

The story of Jesus has become many things to many people across two thousand years, but there's one thing it's not. The story of Jesus is not easy to live or simple to understand. If someone tells you that, cover your ears and run away fast.

In the gospel of John this week, when Jesus called himself the "Living Bread from Heaven," "the Sent One," and "the Holy One of God," the Jews "murmured." They "argued sharply among themselves." Wasn't Jesus the son of Joseph, they asked? Don't we know his parents and family? How can he say such things?

His closest followers were equally baffled. John says that the disciples "grumbled." Who can accept such "hard sayings," they protested?

From that time on, says John, "many of his disciples turned back and no longer followed him."

Nor did Jesus candy coat any of this awkward agitation. "Does this scandalize you?" Jesus asked them. "Do you want to leave too?"

|

|

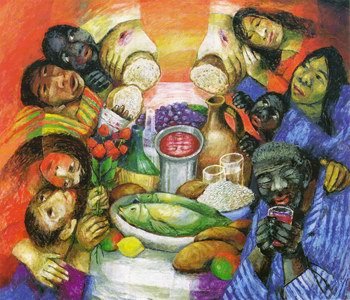

Bread of Life by Kennedy Paizs

|

When Jesus taught in his home town, the village that had helped to raise him "took offense at him." When his family saw the raucous crowds that hounded him, "they went to take charge of him, for they said, 'He is out of his mind.'" John says that "even his own brothers did not believe in him."

This language of scandal and offense echoes Paul's later description of the gospel as "to the Jews a stumbling block and to Greeks foolishness."

In Ephesians 5:32, Paul calls the gospel a "profound mystery." No doubt, that's why he appeals to his readers: "Pray for me, that whenever I open my mouth, words may be given me so that I will fearlessly make known the mystery of the gospel, for which I am an ambassador in chains. Pray that I may declare it fearlessly, as I should."

The word "mystery" is a buzz word to New Testament scholars, and for good reason. It occurs twenty times in the Greek New Testament, sixteen times in Paul, seven of which are in Ephesians alone. At some fundamental level the story of Jesus is an irreducible mystery.

Perhaps gospel faith is a classic case of simplicity beyond complexity or post-critical naivete — it's something that you can describe and affirm but never fully explain.

A mystery isn't unknowable. Paul says that the mystery of the gospel has been fully revealed. It's been disclosed, made manifest, unveiled. But we see it only darkly, as through a cloudy mirror. Who is adequate for these things, Paul asks the Corinthians? No one, that's who.

The story of Jesus began as some sort of "secret." In all three synoptic gospels, right after the greatest of "epiphanies," there's a command of secrecy. "Don't tell anyone what you have seen," Jesus told his disciples after the Transfiguration.

Back in 1901, the German Lutheran scholar Georg Friedrich Eduard William Wrede published a book called The Messianic Secret that explored a motif that's present in all four gospels, and conspicuously prominent in Mark. The phrase stuck, and ever since then "messianic secret" has been scholarly shorthand for this mysterious phenomenon in the gospels.

Depending on how you count them, about 15 different times in the gospels Jesus explicitly suppresses knowledge about his identity. There are at least 13 occurrences in Mark alone. Jesus conceals knowledge about himself in different ways.

Several times he silenced the evil spirits that he exorcised: "he would not let the demons speak because they knew who he was."

He ordered his own disciples to keep silent about what they had experienced — after Peter's confession of Christ as Messiah, and after the Transfiguration.

Jesus also told some of the people he had healed to keep silent: "Jesus sent him away with a strong warning: 'See to it that you don't tell this to anyone.'"

In private discussions away from the crowds, Jesus "explained everything" about the "secret of the kingdom" to his disciples, the insiders, whereas those on the "outside" got only obfuscating parables. And those parables, we read in another place, simultaneously revealed and hid the truth.

When he traveled, sometimes Jesus "did not want anyone to know where they were." In John 7, for example, he went to the Feast of Tabernacles "in secret" in order to hide his identity.

In the beatitudes of Matthew 6, Jesus taught us to give, to pray, and to fast, all "in secret." God the Father, he says, will "see what is done in secret."

Until he burst onto the public scene for three short years of ministry, Jesus lived for thirty years in total obscurity — a secret life about which we know nothing at all.

|

|

The Breaking of the Bread by Sieger Köder.

|

The earliest Christians who worshiped in the catacombs of Rome were criticized by pagans for their secret meetings and bizarre rituals, rumored to include cannibalism, incest, and infanticide. These charges were common enough that numerous second century writers felt constrained to refute them.

And so the historian Garry Wills makes an astute observation. Whereas scholars have long tried to distinguish between the authentic Jesus of real history and the mythical Christ of post-Easter faith, Wills insists that if we were successful in that endeavor, Jesus would appear to us as even more mysterious, not less.

In some places today, confessing the gospel is a means to social acceptance and upward mobility. That was hardly the case for Paul. He was a criminal, not a celebrity.

In the book of Acts, Luke records eight murder attempts on Paul's life. The ninth one was successful. In the epistle this week, Paul writes from a jail cell.

Paul traveled ten thousand miles proclaiming the good news of this secret and mysterious gospel, that God was in Christ revealing his love and redeeming the world.

"Don't be ashamed of the gospel," Paul told the young Timothy. And to the Romans he wrote, "I am not ashamed of the gospel." Why? "Because it is the power of God for salvation to everyone who believes."

Image credits: (1) Blog.renewintl.org and (2) Pastorblog.cumcdebary.org.